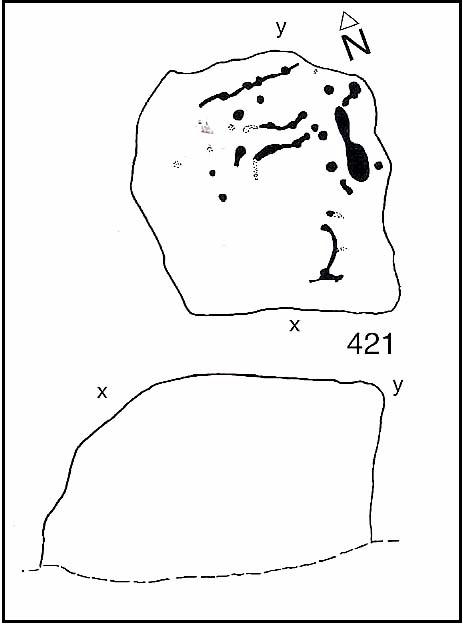

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 08103 61500

Also Known as:

- Carving no.421 (Boughey & Vickerman)

One way is to go east through Appletreewick village up to and through Skyreholme (making sure you bear right at the turn and not go up the left turn, which takes you uphill and elsewhere!) as far as you can drive, where the dirt-track begins. Keep going up till you hit the fork in the tracks, and here, look into the field on your right. The other way is to park up at Stump Cross Caverns on the B6265 road, then walk down the road for 200 yards till you reach the track on your left running towards Simon’s Seat. Walk all the way down this till you reach the fork in the tracks. There’s a gate into the field just yards below the split in the tracks. Go thru it and walk into the middle of the field where the stone unmistakably calls out for you to go sit with it for a while!

Archaeology & History

Sat near a ridge due north of the magnificent Simon’s Seat, this faded carved stone gets its name from the field in which it lives — and as Danny’s photo here shows, it’s a fine stone indeed in a very fine setting. The cup-marks on its top were first described by Stuart Feather (1964), who found there to be around 20 cup-markings on the top, with some grooves — possibly natural, possibly man-made — linking them together.

However, in the fields north of here are a number of other cup-and-ring carvings, but much of the landscape has been damaged by industrial workings. It makes you wonder how many there used to be here before the industrialists started digging the land up…

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Feather, Stuart, “Appletreewick, WR,” in Archaeological Register, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, volume 41, 1964.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Prehistoric Rock Art of Great Britain: A Survey of All Sites Bearing Motifs more Complex than Simple Cup-Marks,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 55, 1989.

Acknowledgements:

Huge thanks to the pseudonymous ‘QDanT‘ for use of the photo in this profile. Cheers Danny!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian