Tumulus (destroyed): OS Grif Reference – SE 4734 2449

Also Known as:

- Mound 1 (Pacitto)

- Roundhill Field

Archaeology & History

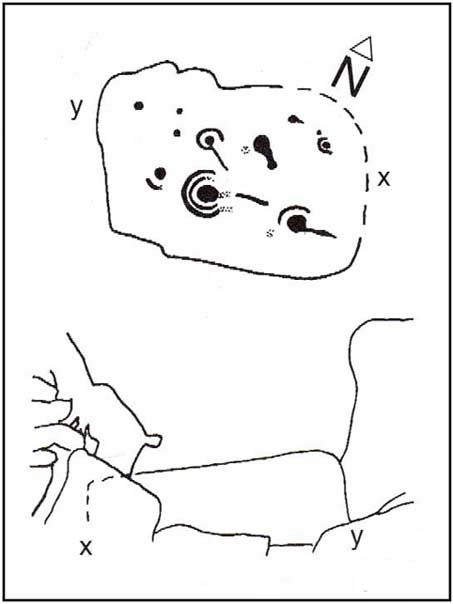

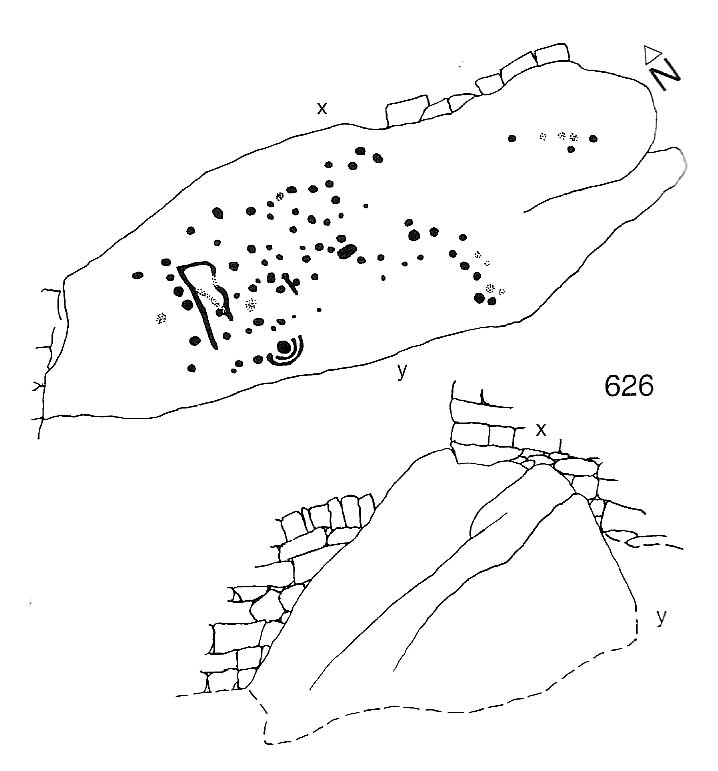

One of a number of sites that used to exist in this part of West Yorkshire before the coming of the Industrialists and their ecocidal ways. Found in conjunction with the Round Hill Field tumulus 53 yards to the south, this fallen monument was thankfully looked over several times before its final demise when the power station was built. The first literary account of it seems to be Forrest’s (1871) local history work, soon followed by another dig by the legendary tomb raider, William Greenwell. (1877) Both of these digs were very good indeed and give us the most detailed account of the remains here.

The name of this tumulus and the nearby Round Hill site needs some clarification before continuing to the archaeological account. In both Forrest and Greenwells’ accounts, they each named this site as the ‘Round hill tumulus’, but since their original fine work, archaeologist A.L. Pacitto (1969) and his team found the other previously unrecorded tumulus and surrounding ring-ditch in the original field called Roundhill field. Old records showed that a wall or fence once ran between the two sites, and that the tumulus which Forrest and Greenwell previously called the Roundhill site was actually located in the curiously named ‘Angel Moon field’ — hence the change of name in this (and Pacitto’s) account. (if y’ get mi drift) It’s an important point. So as you read the accounts below, where the authors describe the Roundhill tumulus, they are in fact referring to this, the Angel Moon tumulus. Gorrit? OK!

The site was noted for the first time as a tumulus by the local owner of the land here, a Mr Hall, in 1811, who wanted it levelled and attempted,

“to remove it altogether, but so many human bones were then met with, that after removing a considerable portion, it was abandoned, and the exhumed bones removed to the neighbouring churchyard of Ferryfryston.”

Mr Forrest then said:

“We are told by an eye-witness that on this occasion two plates of metal were found, but of what kind of metal pr what became of them we have no certain information.”

Thereafter began Forrest’s lengthy account of the initial excavation of the Angel Moon burial mound, undertaken (I think) by himself and other locals. Readers will hopefully forgive the lengthy profile I’ve given this place, but I know it will be of interest to local historians in the Pontefract and Ferrybridge area:

“This Tumulus, which is situated in Roundhill Field, on the left of the road leading from Ferrybridge to Castleford was first opened on March 28th, 1863. For the sake of ascertaining its structure, a trench was dug on the side not previously disturbed, to within a few feet of the centre, but without result, except ascertaining that the material gradually changed from sandy gravel to large stones as the middle was approached, and that it had been raised upon a natural swell of the strata, thus offering a dry situation; a condition about which the ancients appear to have been solicitous in choosing the sites of their sepulchral mounds. They then began to dig at the top, and immediately under the sod lay two human skeletons, one upon the other, with no more than six or eight inches of soil upon them. Near them lay portions of two antlers of…red deer, the uppermost skeleton was that of a tall adult male, the teeth nearly entire and in fine preservation, the other was of shorter but stouter proportions, the feet of both were gone, probably by the diggers in 1811, who it is conjectured had previously discovered these remains, and covered them up, with the few inches of soil, under which we found them; they had evidently not been removed, all the bones present being in their natural position, the whole of the bones and horns were much crushed and broken by the superincumbent earth which must once have covered them.

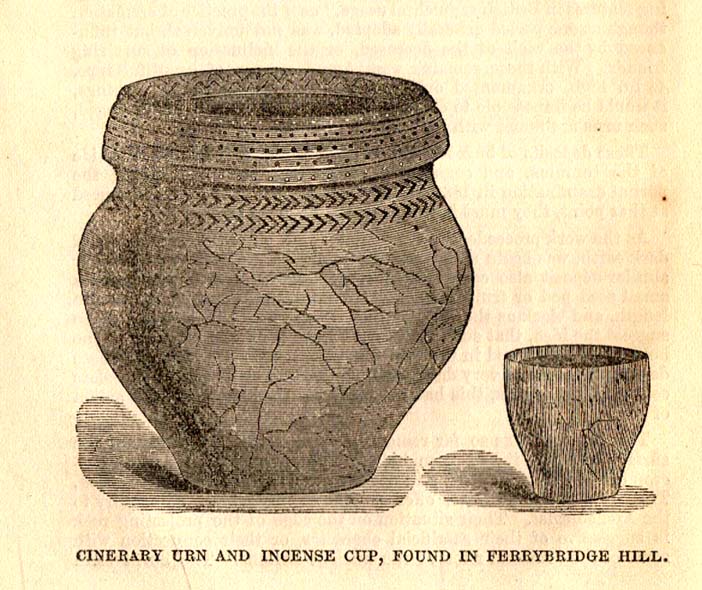

“With them were found several detached pieces of what appeared to have been the tusk of some animal, probably the wild boar, and fragments of half-baked pottery which on comparison were found to be portions of two urns of the early British type, such as are usually found in grave-hills attributed to that period. The smaller one (of which the principal portions were recovered) was of the size and much of the shape of an ordinary breakfast cup, three inches high, scored all over with vertical indentations as if by a piece of flint. The other was much larger, more elegant in shape, on which considerable taste was displayed in the ornamentation, composed of parallel lines, chevrons, zigzags and punctures, in which a dextrous use of the twisted thong was evident; this was ten inches high.

“About eighteen inches to the left of these, and a few inches deeper, lay the skeleton of another person, who had evidently lived to a great age, the teeth being worn nearly to the roots, tho’ showing no signs of decay. All the three lay east and west as in the present mode of Christian sepulture. No other human or animal remains were found, nothing metallic, or any implements, no appearances of cremation, no ashes, neither did the urns appear to have contained any, no stones to indicate that a cist had enclosed them, they had been buried in the soil, which here only differed from that surrounding it, in its somewhat darker colour.

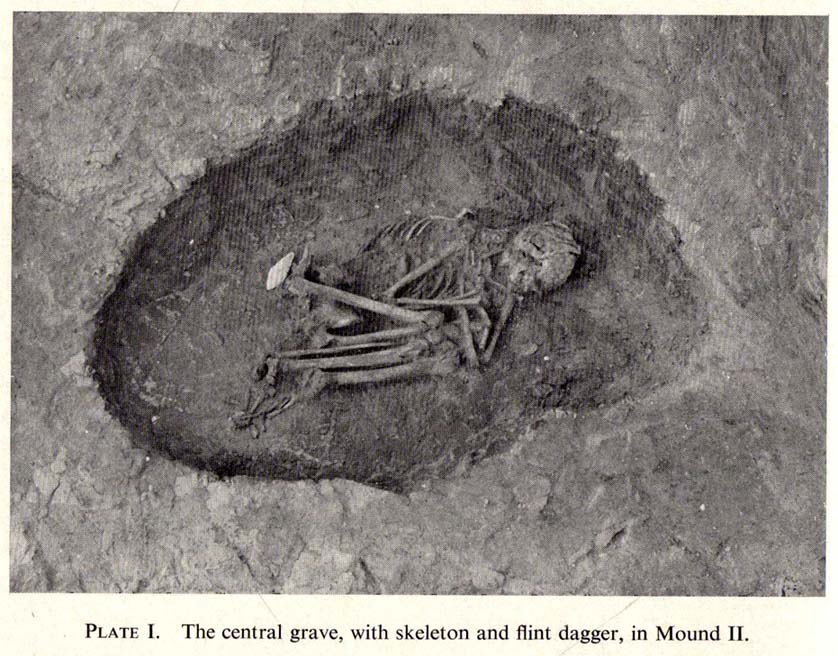

“Digging downward, immediately under the skeletons first discovered, a large rough slab was reached at the depth of four feet from the surface. Its removal disclosed a stone cist or grave, of which it had formed the cover, composed of four rough stones set on edge, and paved with smaller pieces at the bottom; width at the head 2 feet, at the feet 1 foot 5 inches internal dimensions. It was entirely filled with small gravel, in which was interred the skeleton of an adult male, apparently of large stature, the thigh bones measuring in length 19¾ inches, the leg 16 inches. The knees were bent up in the manner in which such interments are usually found, and the face toward the south. The skull was accidentally broken, but well developed, and indicating the age about forty. The teeth were all present, and in beautiful preservation, the enamel white and bright as in the living subject. In front of the breast was an urn, laid on its side, of very coarse make, imperfectly baked, and so fragile, that on the most careful attempt to remove it, the urn crumbled into fragments, the whole was however collected, and sufficed to give a correct idea of its size, shape and ornamentation. It contained nothing but small gravel, like that in which it was laid. Near it was a small chipping of flint with a cutting edge, 2½ by 1¼ inches, this was the only article having any resemblance to a tool or implement hitherto met with.

“The cist being filled with gravel, I suppose to be an unusual circumstance. It could not have penetrated through any fissures in its sides, neither was the cist likely to have been opened subsequently, as nothing appeared to have been disturbed.

“Proceeding downward, it was seen that this cist was built upon and its sides supported by large rough stones inclined towards it ; the surrounding gravel was mixed with fragments of human bones, small pieces of urns, and occasionally bits of charcoal, and in a cavity a piece of wood was found but so decayed that its original shape or purpose could not be ascertained. Among the bones was a portion of a skull, showing a fracture from which the subject had recovered.

“At about the depth of seven feet, and a little to the east was a flat stone laid horizontally, length 4½ feet, width 3 feet, under this was a layer of dark earth two or three inches thick, totally different from that surrounding it, inodorous, and in which was no perceptible trace of animal remains, but exhibiting hollow casts of something resembling stone fruit about 1 inch long by ½-inch wide. Near this was found a thin stone of a round or oval shape about 6 inches broad, apparently chipped to shape and having a rough cutting edge ; its use can only be conjectured.

“At the depth of nine feet, the native rock was reached in which was a cavity about ten inches deep, but as far as could be ascertained containing nothing but gravel mixed with bones like the surrounding part.

“From observations then made I came to this conclusion: that the mound had been used for interments anterior to the formation of the cist, on which occasion, its upper part was levelled to make a convenient platform for it ; when the bones of former interments were disturbed and scattered about with as little respect for the dead as would a modern gravedigger; in making room for a new occupant.

“The fact of the three skeletons first noticed being interred after the Christian mode, is presumptive evidence that they were Saxons. It is well ascertained that this people had their coming here, frequently buried their dead in British tumuli, even after they had embraced Christianity, which occasioned an edict to be published in the year 987, prohibiting this practice, and providing that no Saxon should be buried in the tumuli of the Pagans, but only in the cemeteries of the churches, neither do urns nor antlers (which are undoubtedly British) militate against this supposition, when it is considered that they were all fragmentary, and as the skeletons with which they were, had evidently been disturbed though not removed, it is very probable that these fragments had been taken from that part of the mound removed in 1811, and thrown among these bones in the random manner in which we found them.

“From all these circumstances, this barrow appears to have had a very early and prolonged existence as a place of sepulture. The cavity in the rock was probably the grave of the first interment. The fragments of bones under and around the cist show that interment had taken place before its formation. The absence of any evidence of cremation either in the cist or elsewhere, shows that these interments were prior to the introduction of that ceremony from the nations with whom the Britons afterwards had intercourse. The absence of any weapon or other instrument save the single chipping of flint, and the roughly fashioned stone and the rudely found urn of clay, all go to prove that this was one of the very earliest of British Barrows. And if my hypothesis as to Saxon burial be admissible it will bring its sepulchral history down to the Christian era.

“At the upper end of the field are some earthworks of considerable depth, but as the whole is under cultivation, their form and purpose can scarcely now be determined.”

A few years later the legendary tomb raider Mr Greenwell and his mates turned up and gave the site their additional attention.

“On this occasion the digging commenced on the east side, where a deposit of burnt bones was found upon a flat stone just above the surface, and ten feet from the outside. Six feet to the north of this was another similar deposit laid upon the natural surface. Five feet south of the centre, was an unburnt body, doubled up and on its right side, with its head to the south. Immediately beneath, and in close contact with it, was a burnt body, apparently deposited at the same time. These interments in opposite customs present very interesting features in British sepulchral usage, as if the practice of cremation though at one period generally adopted, was not universal, but influenced by the wish of the deceased, or the inclination of surviving friends. With these remains were found an urn, of beautiful type, 4½in high, ornamented outside with twenty-seven thong markings, it would be impossible to decide to which of the bodies this belonged, such urns are found with both modes of burial.

“These deposits of burnt bodies were all found on the south-east side of the tumulus and consequently none were met with during the partial examination in 1863; but as the diggers in 1811 commenced at that point, they must have found and removed several such.

“As the work proceeded, the large flat stone covering the deposit of dark earth, was again met with ; and southward of this was another similar deposit also covered by a stone. In this earth was found a small seed pod or fruit, with striated markings, about nine lines in length, and black as the soil in which it was found ; its size and shape suggest the idea, that such fruit might have been the occasion of the hollow cists observed in the first discovered deposit. Close to these deposits was one of very dark sand, inclined to dark red or chocolate colour in some parts, this had evidently been subjected to the action of fire.

“The tumulus was so far removed, as to reveal the nature of the surface on which it had been built, which proved to be a natural outcrop of the limestone rock, and upon it these dark deposits were found. Their origin and purpose, offer an interesting subject of enquiry to the Archeologist. Their situation on the edge of the projecting rock is suggestive of their sacrificial character, or their connection with some of the druidical rites of the ancient Britons. The burnt sand may mark the site of the place where the act of cremation had been performed.

“The next object of interest was the rock grave, the edge of which had been reached in 1863, but reluctantly abandoned. This was found, and proved to be a large circular one, nearly six feet in diameter, and two feet six inches deep. At the west end was a rudely-formed cist, filled with gravel like the first one, in which was found a body, bent up in the usual manner, lying on its right side, and with its head to the south-west. At its feet was a drinking cup laid on its side, height seven inches, profusely ornamented with thong markings, consisting of three sets of horizontal lines filled up between with vertical lines, below these, and between two more horizontal lines, was a line of zigzags, the lower triangles of which were filled up with horizontal markings. The same pattern occupied the upper and lower halves of the vase. In the hollow of the knees was found a bronzed pin much oxydized, about 1½in. long, this might have been used to fasten some portion of the dress in which the person had been buried. It was the only piece of metal found in the tumulus, with the exception of that found in 1811, which is now supposed to have belonged to an Anglo-Saxon, buried with sword, spear, shield, etc.”

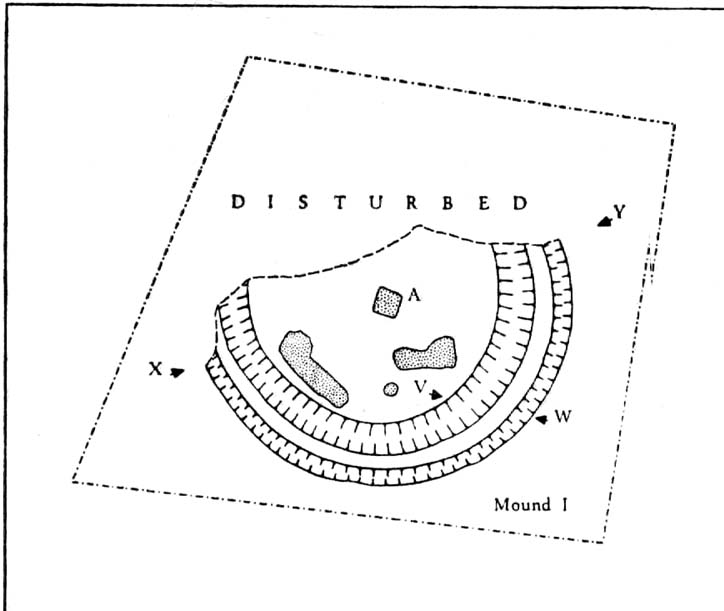

Then in 1962 came the final examination here, shortly before the site’s destruction. Pacitto (1969) and his team didn’t really find much more than his Victorian predecessors, apart from a couple of flints, some other fragments of bones and some modern bits and bats. However,

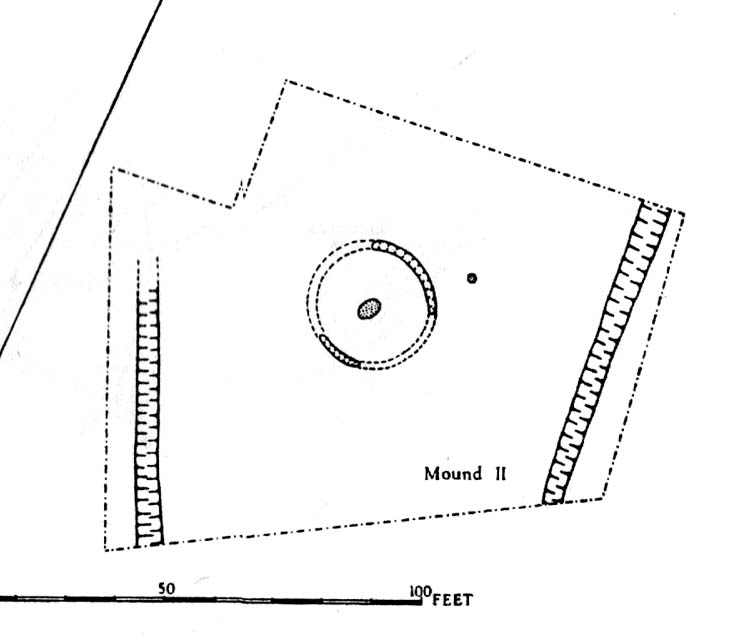

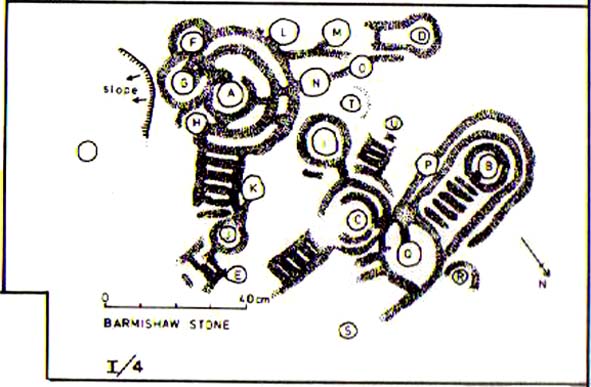

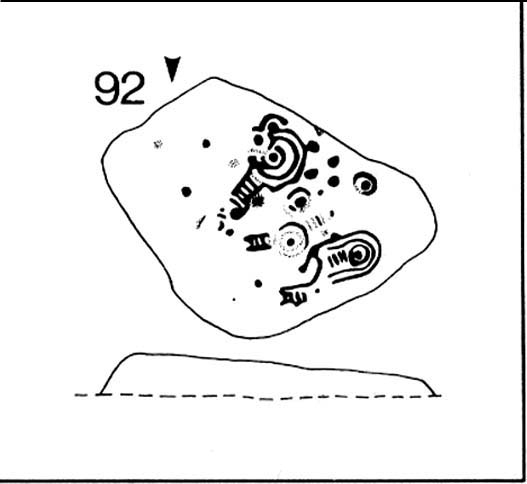

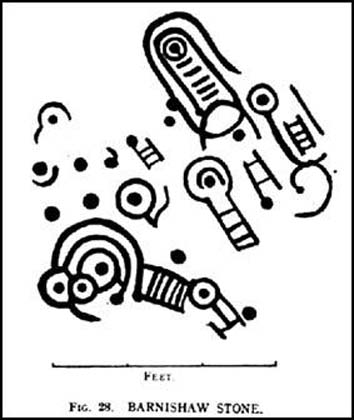

“The mound was surrounded by two concentric ditches, respectively 55ft and 75ft in diameter. The outer ditch was only a few inches deep, but the other had been cut into the limestone (my italics, PB) to a depth of 2ft 6in”

References:

- Forrest, C., The History and Antiquities of Knottingley, W.S. Hepworth: Knottingley 1871.

- Greenwell, William, British Barrows, Clarendon Press: Oxford 1877.

- Pacitto, A.L., “The Excavation of Two Bronze Age Burial Mounds at Ferry Fryston in the West Riding of Yorkshire,” in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, volume 42, part 167, 1969.

- Roberts, I. (ed), Ferrybridge Henge: The Ritual Landscape, WYAS 2006.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian