Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 11193 46417

Also Known as:

- Barnishaw Stone

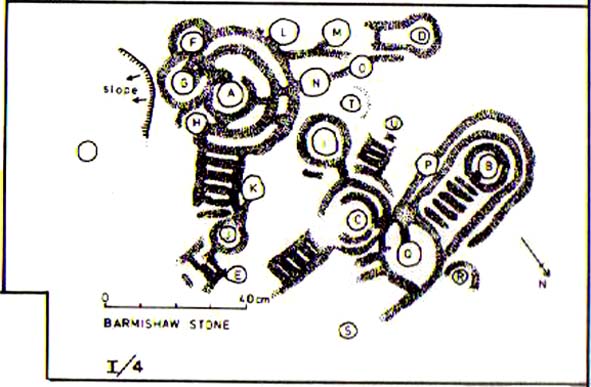

- Carving I/4 (Davies)

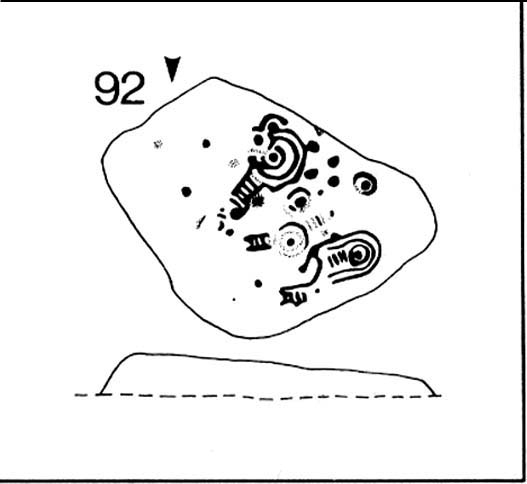

- Carving no.92 (Hedges)

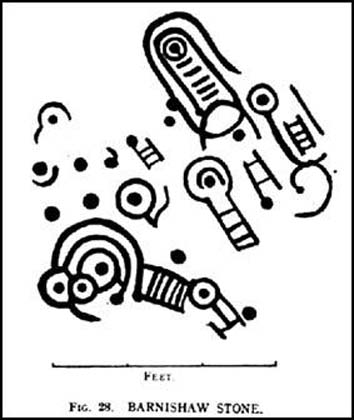

- Carving no.253 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Follow the same directions to reach the superb Badger Stone carving, and from here take the footpath that runs downhill. You’ll cross another footpath about 100 yards down the moor, but just keep walking down the path and you’ll notice the small copse of woods ahead of you. As the footpath begins to swerve roughly away, northeast, heading away from the said woodland, keep your eyes peeled on your left for a reasonably large but flattish rock close to the ground (in summer it’s surrounded by bracken) about 75 yards away. That’s your target!

Archaeology & History

Of the hundreds of cup-and-ring stones on Ilkley Moor and district, this is one of my personal favourites! I first visited the stone in 1977 as a young teenager and was mightily impressed by the unusual nature of the design here — and that impression still remains. Aswell as possessing the usual cups and rings, the Barmishaw Stone is one of just a few rocks also possessing a sort of ‘ladder’ design or linear pattern within the overall carving: an insignia echoed on the nearby Willie Hall Wood carving, the Piper Stone, and also on the Panorama Stones. As with the ‘ladders’ on the Panorama carving, those found here at Barmishaw are very eroded and are increasingly difficult to see during the daytime (the best time to notice them is usually around sunrise or sunset, and particularly when the rock itself is wet).

The carving has been described many times, albeit briefly, by a number of writers. In John Hedges (1986) fine survey he said the following:

“Medium sized flat-topped rock…fairly smooth grit, sloping slightly east to west, covered with carvings, some of which are very worn. Slanting sunshine needed to detect them. About twenty-four cups, at least nine with rings or incomplete rings, two with multiple grooves half round and continuing straight down, one of them incorporating ‘ladder.’ Five other ‘ladders’ – in a good light. Cups mostly deep and clear.” A few years later, Boughey & Vickerman (2003) echoed much of Mr Hedges description, though noted that of the 24 cups with their rings, one possessed a triple ring.

Like so many cup-and-ring stones, they have given rise to hosts of fascinating theories and ideas — one of which is based on mathematics and metrology. In the 1980s, Alan Davies (1983, 1988) surveyed the Barmishaw Stone — and other carvings on Ilkley Moor — to explore the possibility that the cups and rings were laid out according to a basic unit of measure, the Megalithic Inch (MI), as proposed by Alexander Thom some years earlier. Although Davies’ work showed that such a primary unit of measure wasn’t to be found universally, his research at the Barmishaw Stone indicated “significant evidence for quanta of…3 MI,” although this occurred “when the analysis is restricted to only ringed cups.” Despite this, Davies thought that the existence of the Megalithic Inch was evident in this and other carvings on the moors, stating that:

“The repeated emergence of the significance of ringed cups, and the fact that all putative quanta seem to bear a simple numeric relation to each other do not seem to be coincidental.”

However, the selectivity of data in Davies’ research would indicate more that any Megalithic Inches isolated in the metrology of the carvings was due, not simply to chance, but more that the implements used to carve the rocks and the size of the hands of the people doing the carvings was pretty uniform. These simplistic factors need assessing. In modern trials carving cup-markings, we find them to be of similar size to those carved in prehistoric times, as would be expected.

The ladder motif central to this carving may have related to early religious and ritual events here. Across the world, indigenous cultures commonly relate the ‘ladder’ to be a symbol of ascension, both by shamans, mystics and during rites of passage. The symbol represents the journey of the soul to and from supernatural realms. To discount this possibility at the Barmishaw Stone would be shortsighted.

The carving was very probably painted when our neolithic ancestors gathered here, much as Australian aborigines still do to their carvings using lichens and other plant dyes, with the respective ladders and lines changing colour where movements between worlds or shifts of attendant spirit occurred. By virtue of the its very name, I consider this rock to have been considerably important; the “ghost” aspect to barmishaw being a typically misconstrued aspect of ‘spirit’.

Folklore

This excellent cup-and-ring marked stone probably derives its name from the old dialect words “barm i’ t’ shaw”, meaning “ghost in the wood” stone. Whatever guise the attendant spirit of this rock may have had has long since been forgotten; though spectral accounts from the beginning of the nineteenth century until modern times may give us clues. There have been several reports of green-coloured elemental creatures around the area between here and the White Wells sacred spring a short distance to the east. The most recent account, from 1987, took on the modern mythic form of a little green man from space, with attendant UFO to boot! The Barmishaw Hole nearby was a place where faerie-folk used to live. Excesses of geological faulting and water makes the magickal nature of this place particularly potent.

…to be continued…

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Allen, J. Romilly, “Notice of Sculptured Rocks near Ilkley,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 38, 1882.

- Bennett, Paul, “Cup-and-Ring Art”, in Towards 2012, volume 4, pp.83-92, 1998.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Cowling, E.T., ‘A Classification of West Yorkshire Cup and Ring Stones,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 1940.

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way: A Prehistory of Mid-Wharfedale, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Davis, Alan, ‘The Metrology of Cup & Ring Carvings near Ilkley in Yorkshire,’ Science Journal 25, 1983.

- Davies, Alan, ‘The Metrology of Cup and Ring Carvings,’ in Ruggles, C., Records in Stone, Cambridge University Press 1988.

- Eliade, Mircea, Patterns in Comparative Religion, Sheed & Ward: London 1958.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Wright, Joseph, The English Dialect Dictionary – volume 1, Henry Frowde: Oxford 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian