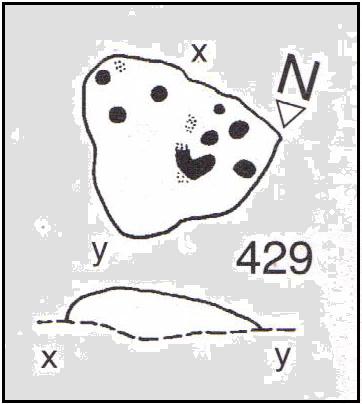

Tumulus (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SY 6800 8600

Also Known as:

- Monument No.1300126 (Pastscape)

Archaeology & History

A number of very large prehistoric burial mounds, or tumuli, were destroyed in this part of Dorset in the 19th century, including “three on the Came estate, near Dorchester, the property of the Hon Col. Damer.” This one—listed as a “bowl barrow” and known today as the Winterborne Came 18b tumulus in Grinsell’s (1959:148) brilliant survey—was found to house examples of petroglyphs, which are very rare in this part of Britain. Thankfully before its destruction, the local antiquarian Charles Warne (1848) was present and has left us with a good description of its structure and contents. After first telling of the demise of two other large tumuli close by, the biggest of them drew his attention:

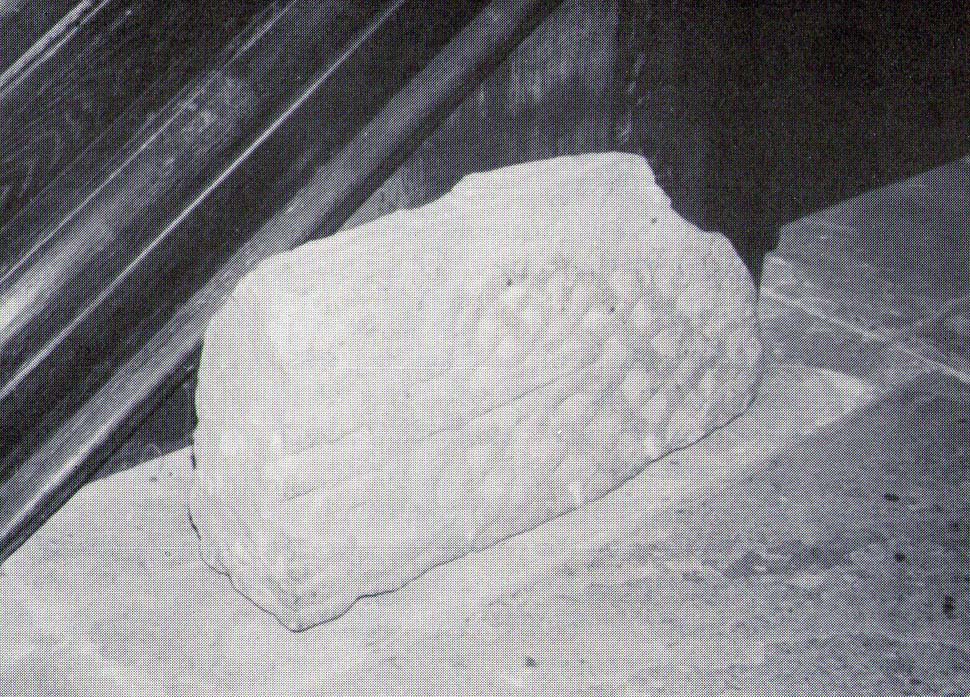

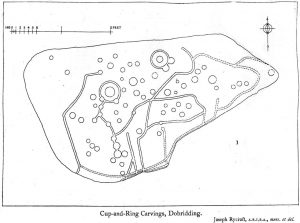

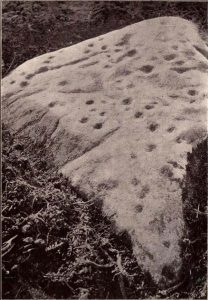

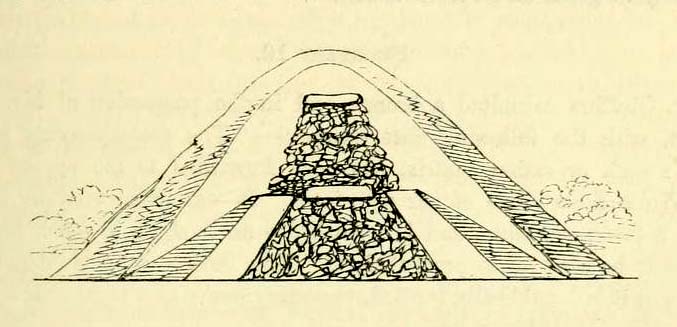

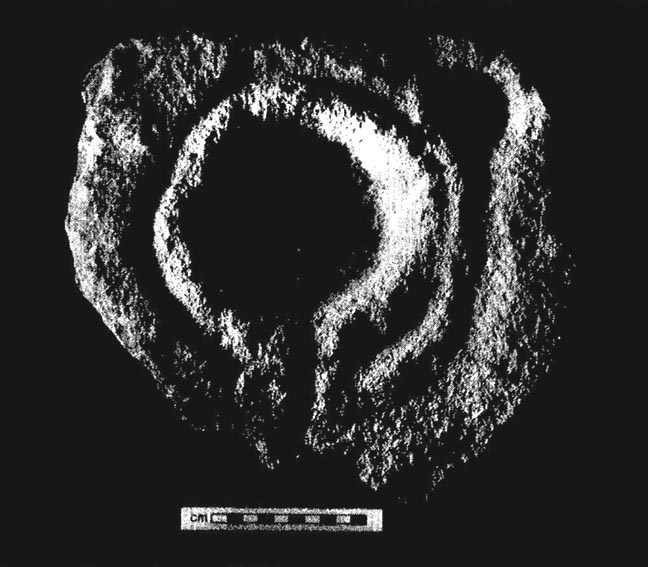

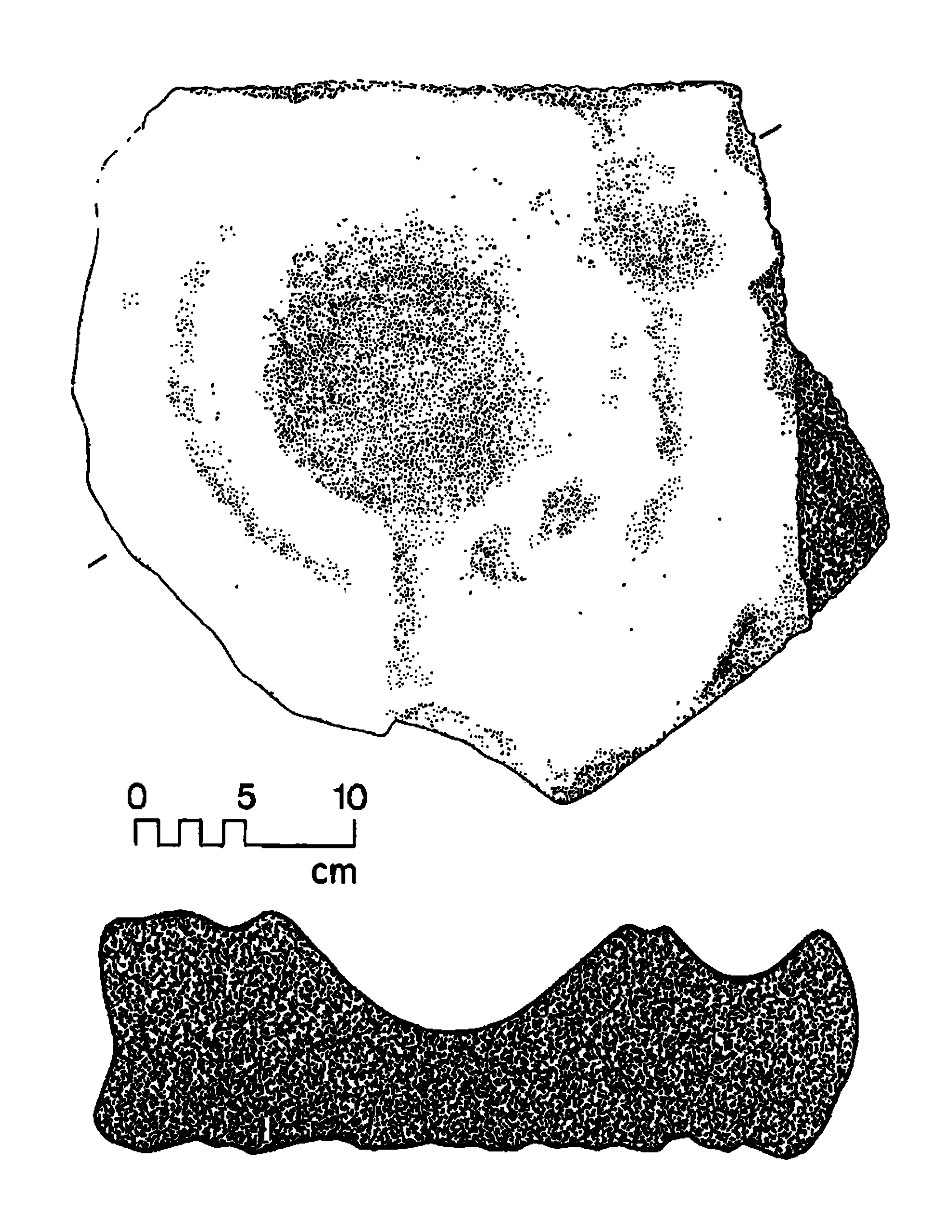

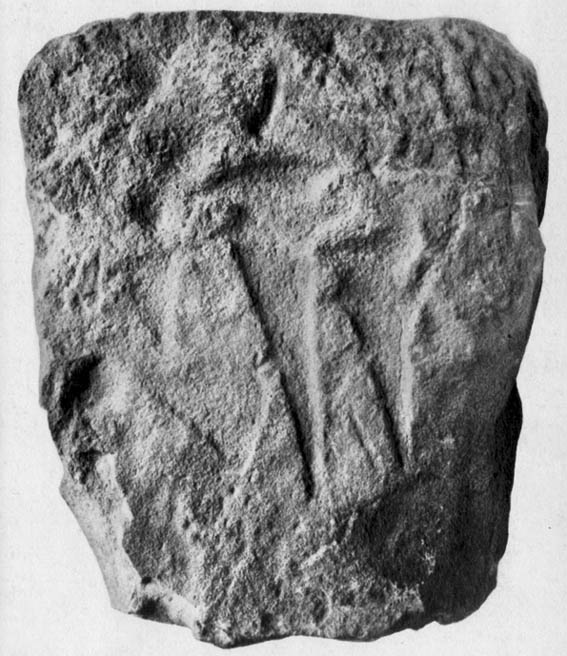

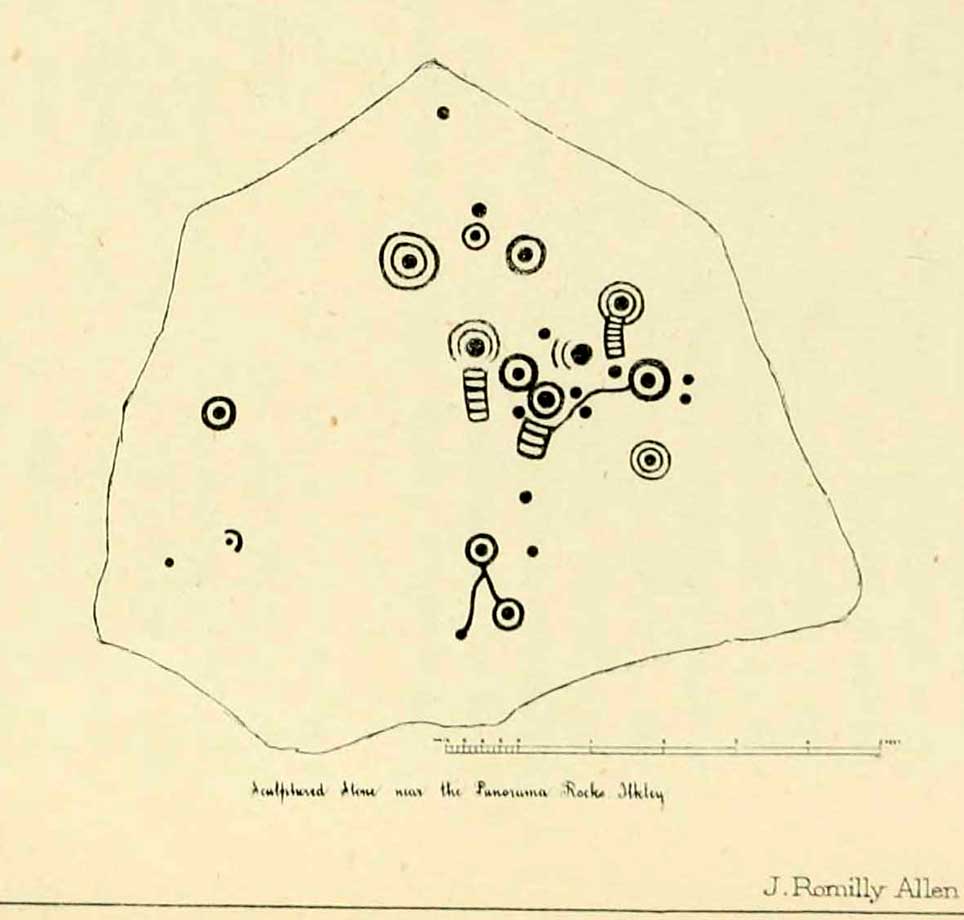

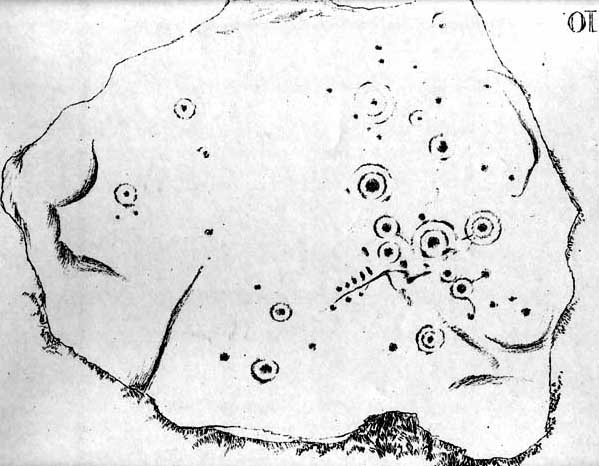

“The last of these mighty mounds (and well do they merit the appellation from their vastness), measured rather more than ninety feet in diameter, and sixteen feet in height; this from the peculiarity of its contents was the most interesting of the three. The annexed rough sketch (above), shewing a central section of the tumulus, may serve to give some idea of the singularity of its composition. About the centre, at a depth of some three feet from the surface, was found lying flat a rough unhewn stone, with a series of concentric circles incised; this, on being removed, was seen to have covered a mass of flints from six to seven feet in thickness, which being also removed we came to another unhewn irregular stone, with similar circles inscribed, and as in the preceding case, covering another cairn of flints, in quantity about the same as beneath the first stone. It was in this lower mass that the deposits were found, consisting of all the fragments of an urn of coarse fabric, and apparently as if placed in its situation without either care or attention, no arrangement of the flints being made (as we have elsewhere seen) for its protection; the want of which observance had completed its destruction. Under the flints, lying at the base, were the remains of six skeletons, and some few bones of the ox. The skeletons had apparently been placed without order or regularity: with the exception of a few bits of charcoal with the urn, there was no evidence of cremation.”

Nearly twenty years later, Sir James Simpson (1867) also described the tumulus and its carved rocks in his 19th century magnum opus, repeating much of Warne’s earlier description, saying:

“In his antiquarian researches in this county (Dorset), Mr Warne opened , at Came Down on the Ridgeway, a tumulus of rather unusual form. At its base…were found the remains of six unburnt human skeletons…and some few bones of the ox. Above them, and in the centre of the tumulus, was built up a cairn or heap of flints around a coarse and broken urn, which contained calcined bones. This mass of flints was surrounded and covered by a horizontal rough slab. Above and upon this slab was built another large heap of flints, six or seven feet in thickness. This second heap was capped with another rough slab, lying two or three feet below the surface of the tumulus. Both these flat unhewn covering slabs had a group of concentric circles cut upon them.”

We don’t know for sure the exact whereabouts of the tumulus, nor the age of the tomb and its remains. But the size of it may indicate an early Bronze Age and perhaps even neolithic status. The finding of the rock art in the tomb is also an indicator that could push the date back into late neolithic period—but we may never know for sure…

References:

- Grinsell, Leslie V., Dorset Barrows, Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society 1959.

- Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), An Inventory of Historical Monuments in the County of Dorset – Volume 2: South-East, HMSO: London 1970.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Warne, Charles, “Removal of Three of the Large Tumuli on the Came Estate, near Dorchester,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 3, 1848.

- Warne, Charles, The Celtic tumuli of Dorset: An Account of Personal and other Researches in the Sepulchral Mounds of the Durotriges, J.R. Smith: London 1866.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian