Long Barrow: OS Grid Reference – SP 2975 2107

Pretty easy really. From Shipton-under-Wychwood take the A361 road north (to Chipping Norton) for just over 2 miles. You’ll pass the TV mast on your right and then a small country lane sign-posted to Ascott-under-Wychwood. Go past this and then stop at the next right-turn a half-mile further up the road. The barrow is about 100 yards before this turning, in the hedgerow, on the left-hand side of the road!

Archaeology & History

This once great and proud neolithic monument is today but a shadow of its former self. Described by various antiquarians and archaeologists over the years, O.G.S. Crawford (1925) included it in his fine survey, telling:

“The barrow is between 160 and 170 feet long and stands in two fields on the west side of the Chipping Norton and Burford main road… In the northern field, at the NE end of the barrow, stands a single upright stone, 6 feet high, 5 feet broad and 1 foot 6 inches thick. This stone is stated to be buried three feet deep in the ground and its height is given by Conder as 10 feet 6 inches. When visited October 18, 1922, a large piece of the top had been broken off, but replaced in position.”

This damage was reported around the same time and described in the early “Notes” of The Antiquaries Journal by a Mr A.D. Passmore (1925), who wrote:

“About 30ft from the north-east end of this long barrow stands a large monolith now nearly 6ft above ground…and roughly 6ft wide and just under 2ft thick, of local stone. At the top is an ancient and natural fissure extending right across the stone and penetrating some way downwards obliquely. Early in 1923, either by foul play or natural decay, another crack appeared spreading towards the first about a right-angle, the result being that a large piece at the top of the monolith became detached. Such an opportunity of mischief was speedily taken advantage of and the piece of stone, weighing over 4 cwt, was pushed off and fell to the ground. In August 1924 the owner of the land, his man, and the writer spread a bed of cement and hoisted up the large broken mass and relaid it in its bed.”

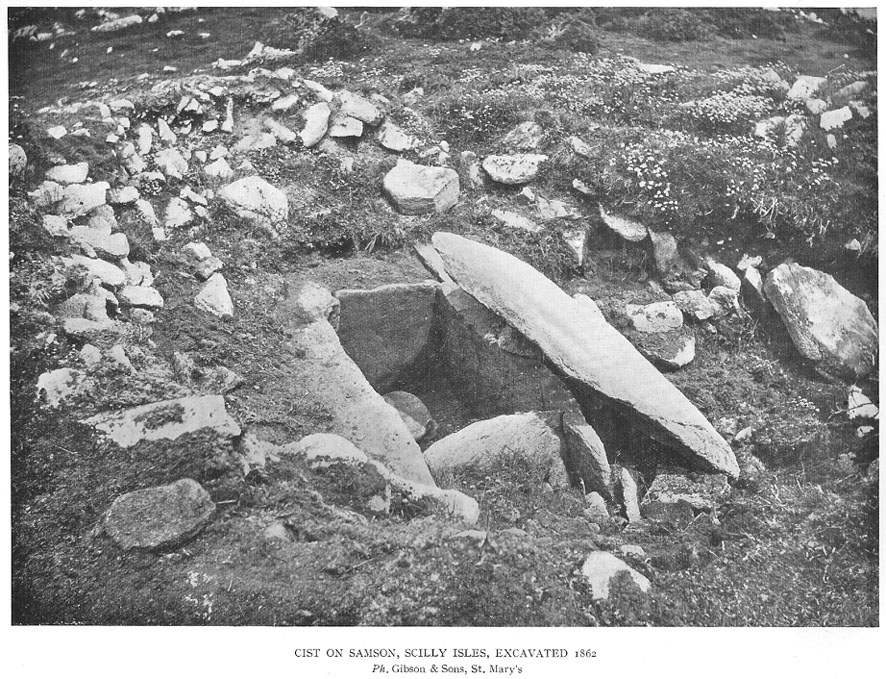

But even in their day, the tomb had already been opened up and checked out, by a Lord Moreton and a Mr Edward Conder, in 1894 no less! Conder’s account (1895) of the inside of this ancient tomb told:

“There were found (1) a chamber at right angles to the long axis of the barrow; on the south-eastern side of the barrow were two uprights, 4 feet 2 inches by 2 feet 1o inches, and 1 foot 9 inches by 2 feet 8 inches. At the north-western end of the chamber were two uprights set with their long faces (edges?) abutting. On the surface-line at the level of the base of the barrow were traces of paving and fragments of bone, pottery and charcoal. (2) Chamber, a little south of the south-east corner of No.1, slightly above the ground level. It was formed of three uprights, on the north, east and west sides respectively, and a paving slab with a perforation 4 inches in diameter. At the north-eastern end of the barrow was a ridge of large ‘rug’ stones up to 8 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 2½ feet thick, terminating in a standing stone…10 feet 6 inches high…buried 3 feet below ground level. At the southwest end was a standing stone, 4½ feet by 3 feet by 11 inches thick, in a horizontal position lying east and west, 2 feet below the surface. At various points were found skulls and human and animal bones and hearths, with no indications of date, and (as secondary interments) two Saxon graves.”

Today, poor old Lyneham Barrow is much overgrown and could do with a bittova face-lift to bring it back to life. But I wouldn’t hold y’ breath…..

Folklore

At the crossroads just above this old tomb, the ghost of a white lady is said to roam. And at the old quarry on the other side of the road a decidedly shamanistic tale speaks of an old lady who lived in a cave and guarded great treasure! Her spirit is sometimes seen wandering about in and around the fields hereby.

References:

- Bennett, Paul & Wilson, Tom, The Old Stones of Rollright and District, Cockley: London 1999.

- Brooks, J.A., Ghosts and Witches of the Cotswolds, Jarrold: Norwich 1992.

- Conder, Edward, “An Account of the Exploration of Lyneham Barrow, Oxon,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, volume 15, 1895.

- Crawford, O.G.S., Long Barrows of the Cotswolds, John Bellows: Oxford 1925.

- Dyer, James, Discovering Regional Archaeology: The Cotswolds and the Upper Thames, Shire: Tring 1970.

- L.V. Grinsell’s Ancient Burial Mounds of England, Methuen: London 1936.

- James, Dave, “A Brief Foray into Oxfordshire,” in Gloucestershire Earth Mysteries 14, 1992.

- Passmore, A.D., “Lyneham Barrow, Oxfordshire,” in Antiquaries Journal, 5:2, April 1925.

- Turner, Mark, Folklore and mysteries of the Cotswolds, Hale: London 1993.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian