Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 0087 4753

Also Known as:

- Black Hill Cairn

- Bradley Moor Round Cairn

- Queen’s Cairn

Getting Here

Various ways here. Best is probably taking the footpath onto Farnhill Moor a few hundred yards east of Kildwick Hall. Head for the cross-bearing Jubilee Tower (supposedly built upon an ancient cairn), NW, keep going past it uphill until you reach the walling 350 yards north, where a seat let’s you have a rest. Climb over the wall! Alternatively, walk eastwards and up through the steep but gorgeous birch-wooded slopes of Farnhill Wood; and as the moortop opens up before you, the great pile of rocks surmounts the skyline ahead. You can’t miss it! (NB: the spot cited on the OS-map as the cairn is in fact another site, 100 yards NW)

Archaeology & History

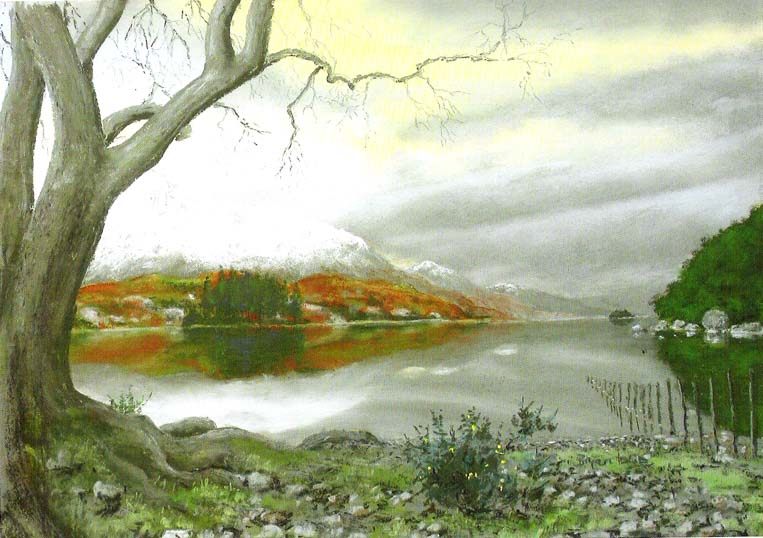

Its an awesome place in an awesome setting. You can see 360-degrees all round from this giant mass of rocks — something which was of obvious importance to the people who built it. If it had been placed 20-30 yards either side of here, that characteristic would not occur. Indeed, this is the only place anywhere on these moors where such a great view was possible. Important geomancy, as they say (or whatever modern term they give it these days).

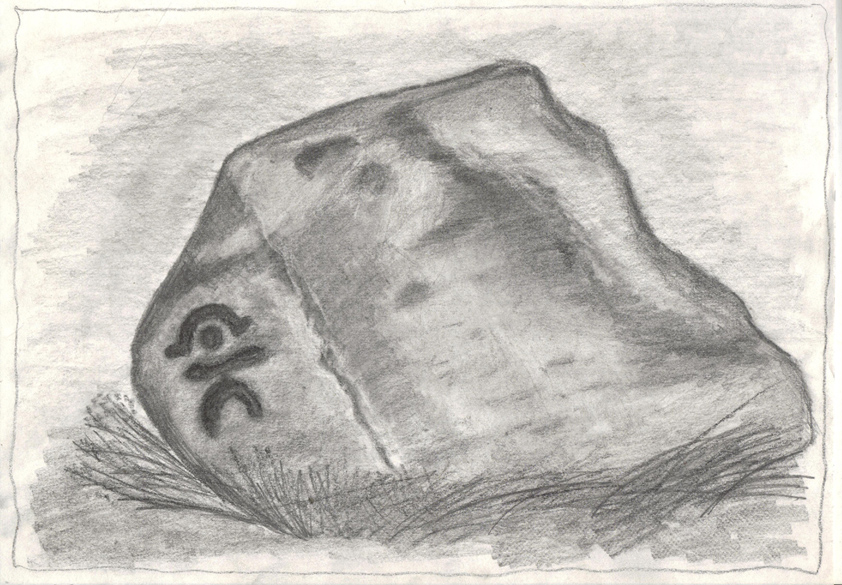

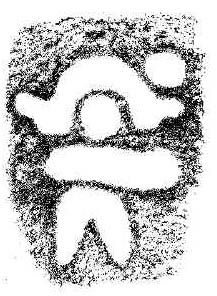

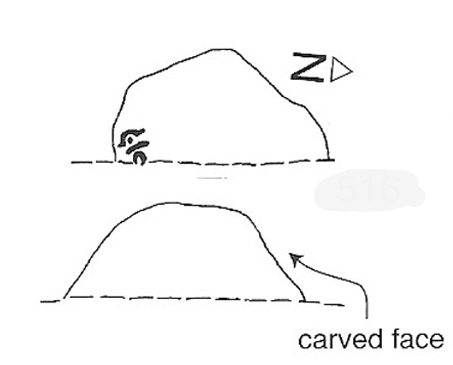

Although the tomb is still of considerable size (at least 100 feet across) and made up of thousands of stones, it has been severely robbed of stone in years passed, for walling and other building materials. A number of other small cairns scatter the heathlands a few hundred yards roundabout this central giant (though are hard to find in the deep heather); and there is a distinct cairn circle about 100 yards to the northwest, which has yet to be excavated. This cairn circle can be made out quite easily if you stand on the ridge about 30 yards west of here, looking down the slope. An then of course we have the equally huge Black Hill Long Cairn, less than 100 away, aligned northwest-southeast, which obviously had an important archaeological relationship with this giant round cairn. Also around this and the adjacent long cairn, numerous flints and scrapers have been found, showing humans have been here since at least the early neolithic period. And recently, what seems to be a fallen standing stone has been found laying in the heather, 168 yards to the north.

This site in particular gives me the distinct impression that it was the most important of the various sites upon these moors. It’s got a distinctly female flavour to it – and it’s old name of the Queen’s Cairn seems just right. Maybe it’s the fact that when I first visited the place, a great thunderstorm broke through the previously perfect skies, scattering lightning bolts all round for perhaps thirty minutes — so I stripped myself naked and reached my arms out-stretched, cruciform, screaming to the skies in the pouring rain! Thereafter, no clouds appeared in the skies for the rest of the day. It was a brilliant welcome to the place!

References:

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey, I, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Raistrick, Arthur, ‘Prehistoric Burials at Waddington and Bradley,’ in YAJ 119, 1936.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian