Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – SP 33923 23544

Best visited out of season before the corn’s been planted. It makes it easier to find and doesn’t annoy the land-owner here, who tends to be a decent dood. From Chipping Norton go southeast along the B2046 road to Charlbury. After about 1½ miles take the second right turning down the small country lane. Go slowly down here for less than half a mile, watching the fields on your right. You’re damn close!

Archaeology & History

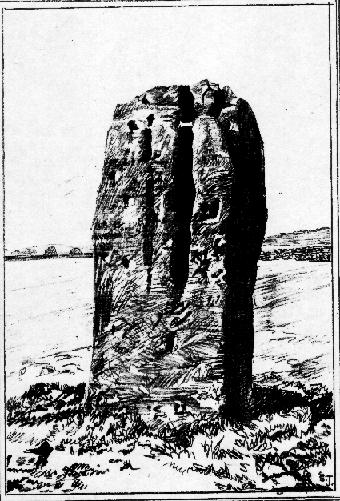

This impressive, weather-worn, eight-foot tall standing stone stands aloft in the middle of a field due west of the road between Chalford Green and Dean. It’s an excellent monolith and one which, I think, has a lot more occult history known of it than described here. Thought by O.G.S. Crawford (1925) and others in the past to have been “formerly part of a chambered structure,” or prehistoric chambered tomb like that of the Hoar Stone at nearby Enstone, no remains of such a structure unfortunately remain today. It is first illustrated and named on a local map of the region in 1743 CE, and the stone at least has fortunately managed to escape the intense agricultural ravages endemic to this part of the country.

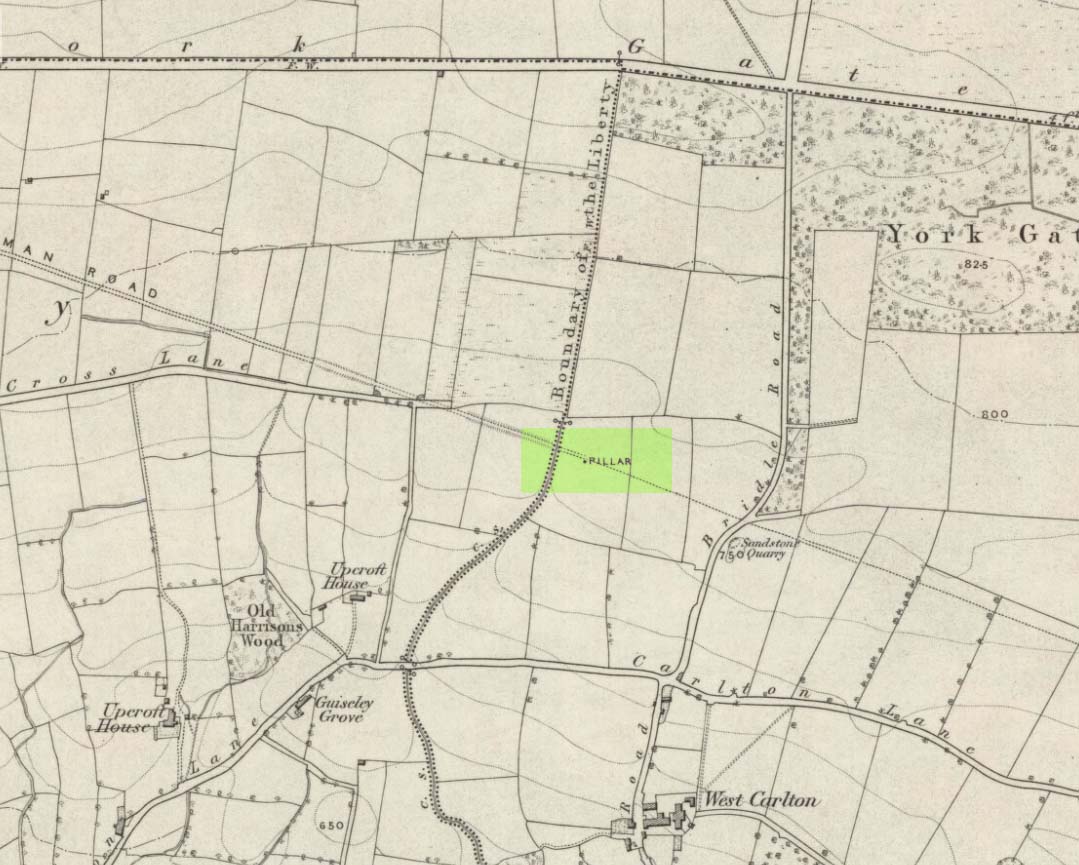

The name “Hawk” stone has been fancied by some to relate to some obscure resemblence to a Hawk, or because there very often are hawks hovering over those upland fields – but these are unlikely. It’s thought by place-name authorities more likely to derive from a corruption of ‘Hoar’ meaning a grey or boundary stone; and as it stands just yards east of the present township boundary line, this derivation seems more probable.

To all lovers of megalithic sites, we highly recommend a visit here!

Folklore

In local folklore and in the opinion of some earlier historians, the Hawk Stone formed an integral part of a stone circle here, but there is little known evidence to substantiate this.

A creation legend attached to this site tells that the stone was thrown, or dragged across the land, by a old witch or hag — though we are not told from where. This is a motif found at megalithic sites all across the country (see Bord & Bord 1977; Grinsell 1976, etc). In Corbett’s History of Spelsbury (1962) the author told of the folklore spoken of by one Mr Caleb Lainchbury who

“said the cleft at the top of the Hawk Stone at Dean was supposed to of been made by the chains of the witches who were tied to it and burnt. As witches seem to have been extremely rare in Oxfordshire it cannot have been a very common practise to burn them at Dean; but there may indeed have been some kind of fire ceremonies near the stone.”

Grinsell (1976) also tells how the Hawk Stone has that animistic property, bestowed upon other old monoliths, of coming to life and going “down to the water to drink when it hears the clock strike 12.”

This evidently important and visually impressive monolith also plays an important part in an incredibly precise alignment (ley) running roughly east-west across the landscape. At first, Tom Wilson (1999) thought the alignment had previously gone unnoticed, but later we later found a reference to the same line in an early copy of The Ley Hunter (Cooper 1979). It links up with other important megalithic sites, such as the Hoar Stones at Enstone, Buswell’s thicket, and the ancient Sarsden Cross.

Similarly, when Tom Graves’ (1980) was doing some dowsing experiments at the Rollright stone circle a few miles west, he found what he described as an ‘overground’ (or ley) linking the ring of stones to the Hawk Stone, but no other connecting sites are known along this line.

References:

- Bennett, Paul & Wilson, Tom, The Old Stones of Rollright and District, Cockley: London 1999.

- Bord, Janet & Colin, The Secret Country, BCA: London 1977.

- Cooper, Roy, “Some Oxfordshire Leys,” in The Ley Hunter, 86, 1979.

- Corbett, Elsie, A History of Spelsbury, Cheney & Sons: Banbury 1962.

- Crawford, O.G.S., The Long Barrows of the Cotswolds, John Bellows: Gloucester 1925.

- Gelling, Margaret, The Place-Names of Oxfordshire – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1954.

- Graves, Tom, Needles of Stone, Granada: London 1980.

- Grinsell, L.V., Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain, David & Charles: Newton Abbot 1976.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian