Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SE 6038 5219

Also Known as:

- Holy Well, York Minster

Archaeology & History

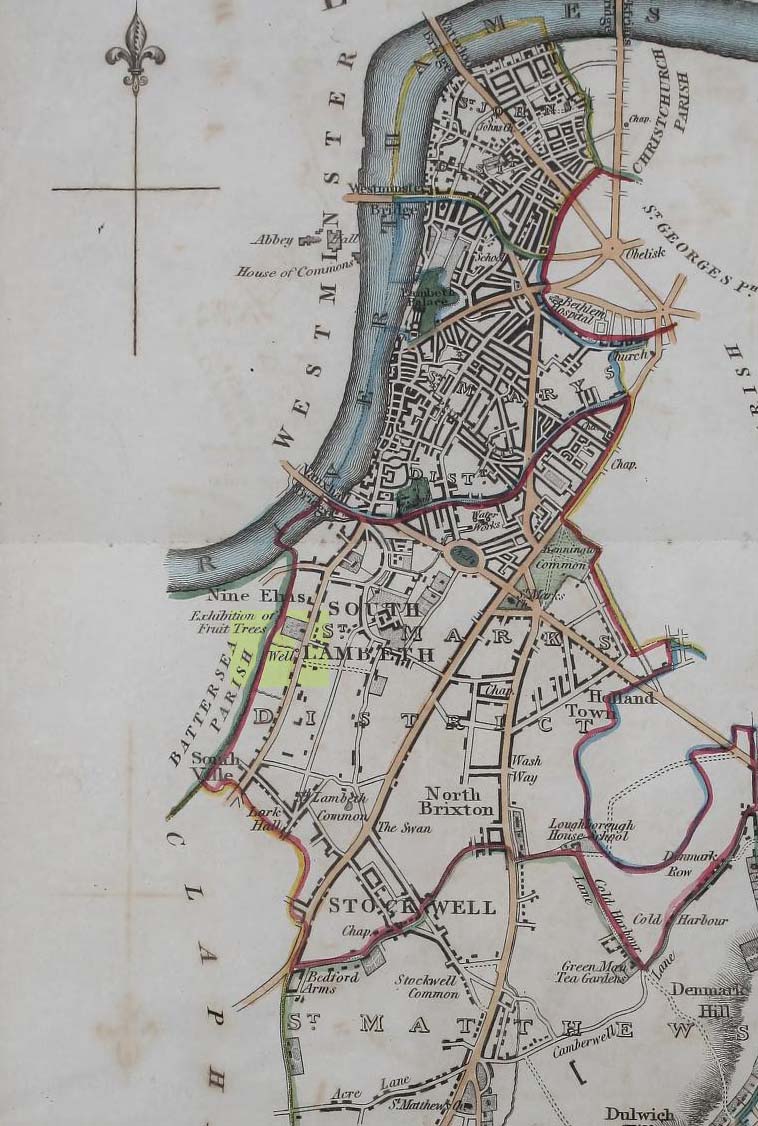

Old photo of the well

For people who like to visit the sacred sites that determined a cross-over from Earth-based animism to one which ceased sanctifying the Earth, this ancient water source in the cellars beneath York Minster would be a good example. Sadly, the church has closed off access to this ancient heritage and you can no longer see it. Yet despite the fact that the modern-day christians have closed off your encounter with this important heritage site (York Minster’s website doesn’t even mention its existence!), we should not forget its mythic history…

As you walk into the building (at some great expense, it has to be said), the location of the holy well is said to be at its more western end, albeit in the crypt underground—although there does seems to be some confusion with some authors about exactly where the well is positioned.

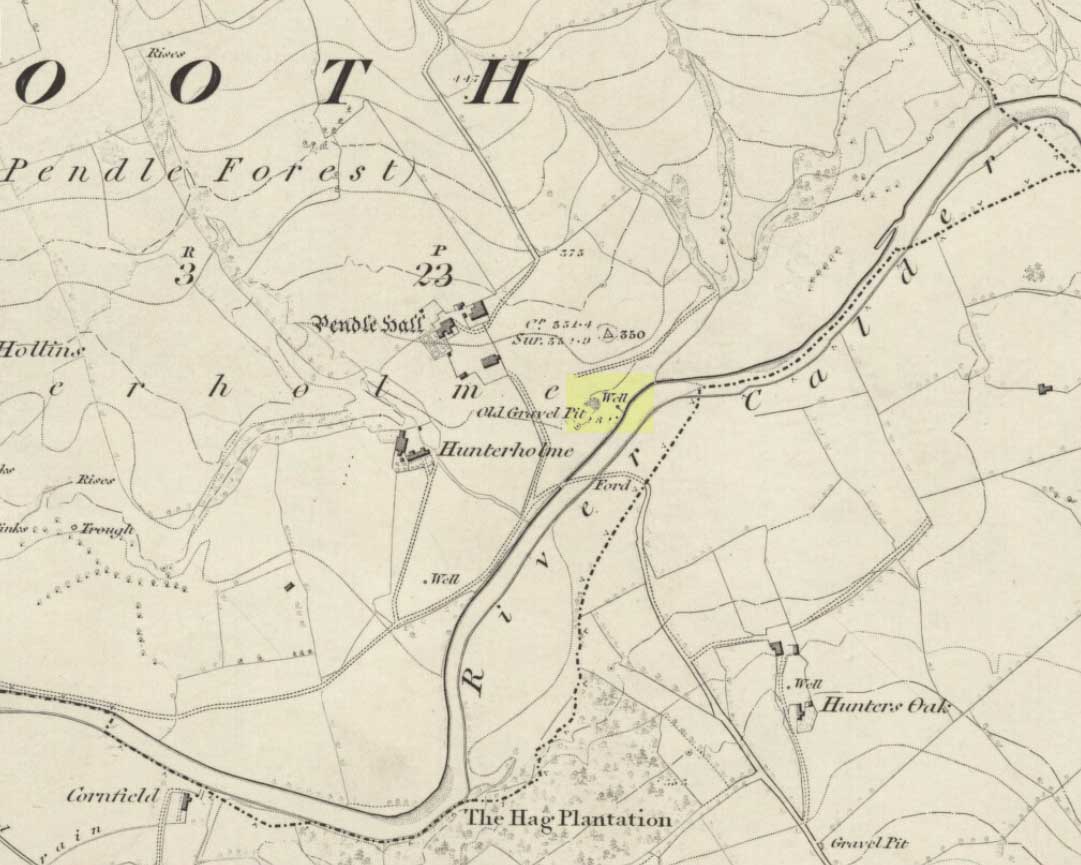

1850 sketch of the well

The earliest account we hear of the place relates to when the northern tribal King Edwin, along with his sons Osfrid and Esfrid, came here to be “baptized” in the waters of this clear spring “on Easter day, April 12, 627” CE. Immediately thereafter a small wooden chapel was constructed next to or above the well. From then on, as the centuries passed, the renown of the well grew and eventually the magnificent ritual temple of York Minster was eventually built. The waters eventually became dedicated to St. Peter and an annual festival occurred here soon after the Midsummer solstice on what became known as St. Peter’s Day (June 29). After the year 1462, a secondary festival date was also given to the site by the Church and another annual celebration occurred here on October 1 too. Its waters remained accessible to people for drinking, healing and rites throughout the centuries. It is only now, in the 21st century, that its sacrality and spirit has been closed-off. This is a situation that must be remedied!

In Mr Goole’s (1850) survey of York Minster, his architectural illustration of the building showed that the water from the well had been brought up onto the ground floor, on the southeast side of the inner cathedral building in the easternmost vestry, and named as St Peter’s Pump. This is illustrated in the 1850 drawing above-left.

A whole series of early writers mention the well in earlier centuries—of whom a brief sample is given here. When Celia Feinnes came here in the 17th century, she said that,

“In the vestry of York Minster there is a well of sweet spring water called St Peter’s Well ye saint of ye Church, so it is called St Peter’s Cathedral.”(Smith 1923)

Mr Torre (1719) gave it equal brevity, saying simply that,

“at the south-west corner thereof is a draw-well (called St. Peter’s Well) of very wholesome clear water much drunk by the common people.”

In R.C. Hope’s (1893) national survey of sacred wells, he told that

“There is a draw well with a stone cistern in the eastern part of the crypt of York Minster… The Crypt is about 40 feet by 35 feet.”

The well was even included in Murray’s Handbook to Yorkshire (1892) as being “in the southwest corner of the Minster.” William Smith (1923) included the site in his fine survey, telling his readers that,

“The water is excellent in quality, which in measure, so chemists say, is due to the lime washed into it by the rain from the walls of the Minster. The water has for centuries been used for baptisms, and is so used today. The well has now for some years been covered with a pump.”

Folklore

In Geoffrey of Monmouth’s famous early History, we find that King Arthur visited here. …And one final note, about which we know not for certain whether it was relevant to the holy well hiding in the crypt, but a fascinating heathen custom was enacted here in bygone days, almost above the spring. Mistletoe, as Christina Hole (1950) told,

“was ceremonially carried to the cathedral on Christmas Eve and laid upon the high altar, after which a universal pardon and liberty for all was proclaimed at the four gates of the city for as long as the branch lay upon the altar.”

Mistletoe is one element that is known to have been sacred to the druids (not the present-day druids!) and was sacred to the ancient Scandinavians (who came here), and also possessed the powers of life and death in its prodigious folklore and phytochemistry. Fascinating…

References:

- Bord, Janet, Cures and Curses: Ritual and Cult at Holy Wells, HOAP: Wymeswold 2006.

- Gutch, Mrs, County Folk-lore volume 2 – North Riding of Yorkshire, York and the Ainsty, David Nutt: London 1901.

- Hole, Christina, English Custom and Usage, Batsford: London 1950.

- Hole, Christina, English Shrines and Sanctuaries, Batsford: London 1954.

- Hope, Robert Charles, Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England, Elliott Stock: London 1893.

- Murray, John, Handbook for Travellers in Yorkshire, J.Murray: London 1874.

- Parkinson, Thomas, Yorkshire Legends and Traditions, Elliot Stock: London 1888.

- Poole, G.A., An Historical and Descriptive Guide to York Cathedral and its Antiquities, R. Sunter: York 1850.

- Purey-Cust, A.P., York Minster, Isbister: London 1898.

- Rattue, James, The Living Stream: Holy Wells in Historical Context, Boydell: Woodbridge 1995.

- Smith, William, Ancient Springs and Streams of the East Riding of Yorkshire, A. Brown: Hull 1923.

- Torre, James, The Antiquities of York, York 1719.

- Whelan, Edna, “Holy Wells in Yorkshire – part 1,” in Source, No.3, November 1985.

- Whelan, Edna, The Magic and Mystery of Holy Wells, Capall Bann: Chieveley 2001.

- Whelan, Edna & Taylor, Ian, Yorkshire Holy Wells and Sacred Springs, Northern Lights: Dunnington 1989.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian