Enclosure: OS Grid Reference – SE 13890 45516

From Ilkley, take the Cowpasture Road up past Cow & Calf rocks, the hotel and along the moorside. A few hundred yards further, just before the next farm-building on your right, walk up the Rushy Beck path to the top. Crossing the stream at the top, now walk diagonally south-ish into the heather for some 200 yards, a short distance before the hillside begins to rise up again onto the next ridge. Remains of this ‘enclosure’ is all around you!

Archaeology & History

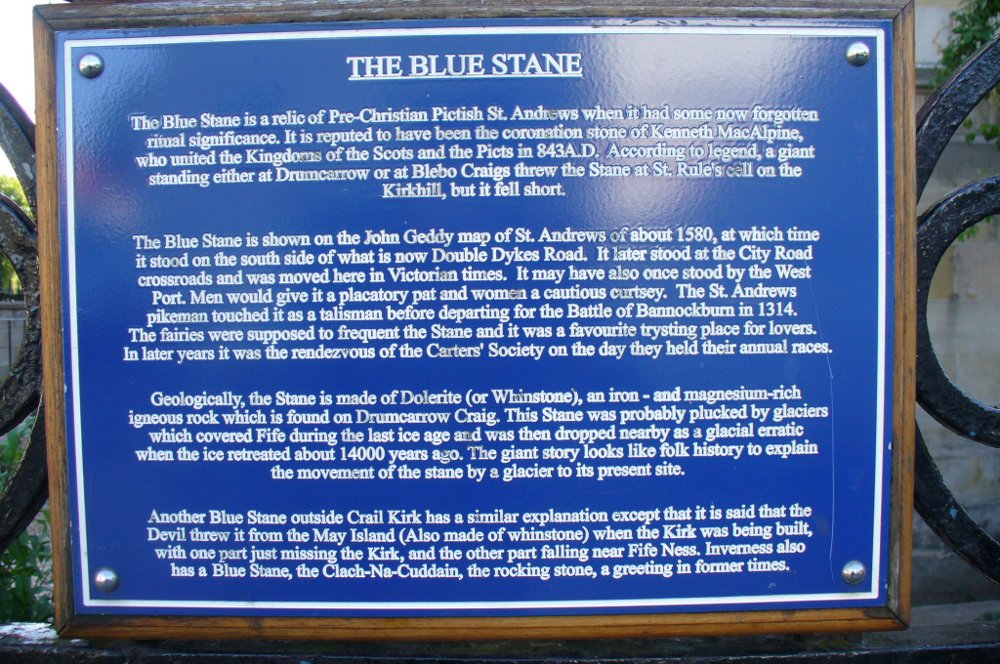

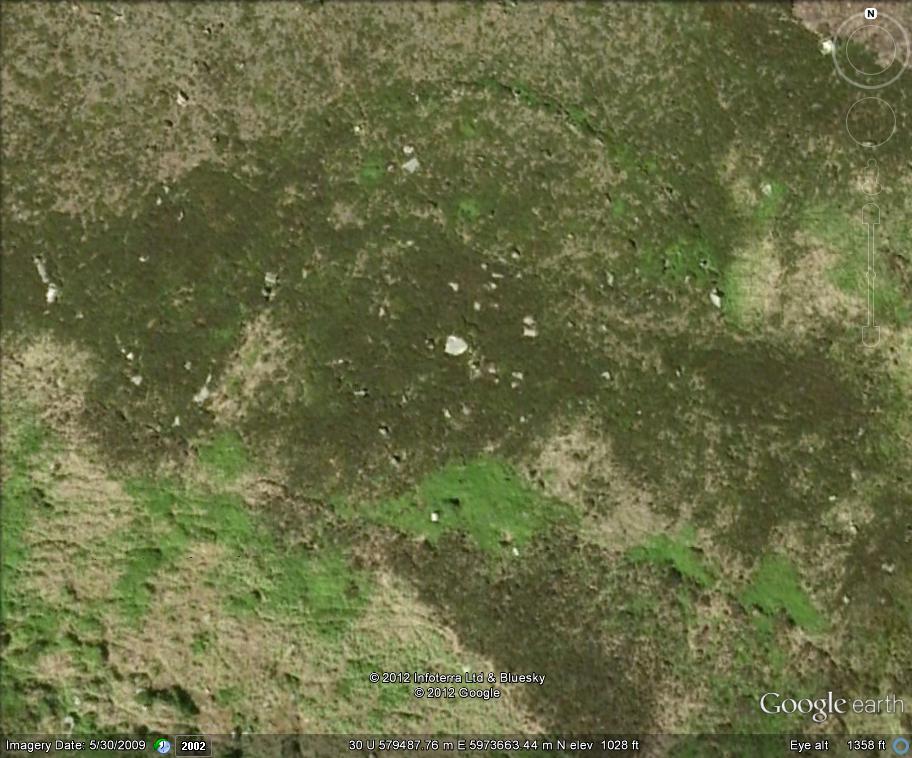

When the normal moorland vegetation covers this prehistoric site, you’d barely know there was anything here apart from various rocky rises and undulations in the ground and perhaps, if you were seeking out old stuff, what would seem to be lines of stone walls bending away onto the moor. But when the heaths have been burnt back, a whole new vista unfolds itself! You see before you a fantastic, well-preserved, unexcavated prehistoric enclosure, whose origins are probably neolithic, but whose history and use stretched through the Bronze Age and into the Iron Age—and it’s not alone! East, west and south of this particular enclosure, other prehistoric walled structures are found stretching all across the landscape hereby, structurally similar and also used over very long periods in prehistory. For antiquarians and historians alike, this is a truly impressive place indeed. In all honesty, the description I give here does not do the place justice!

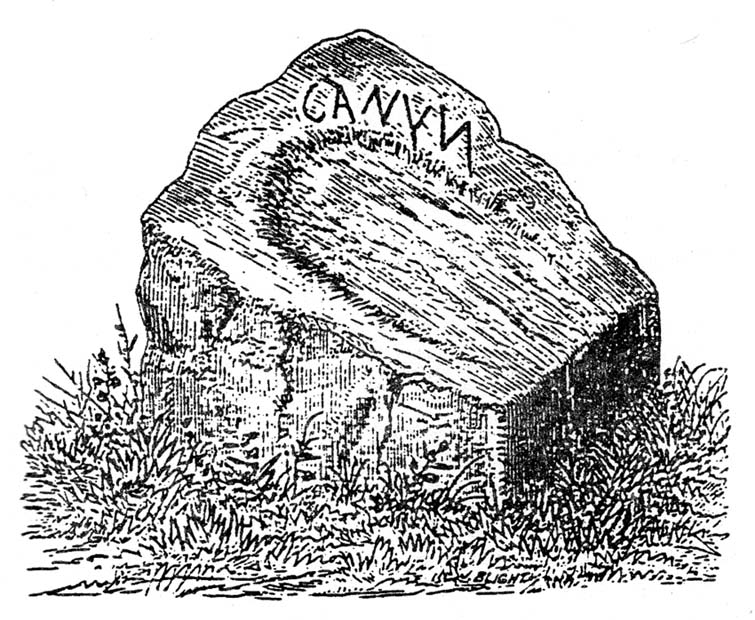

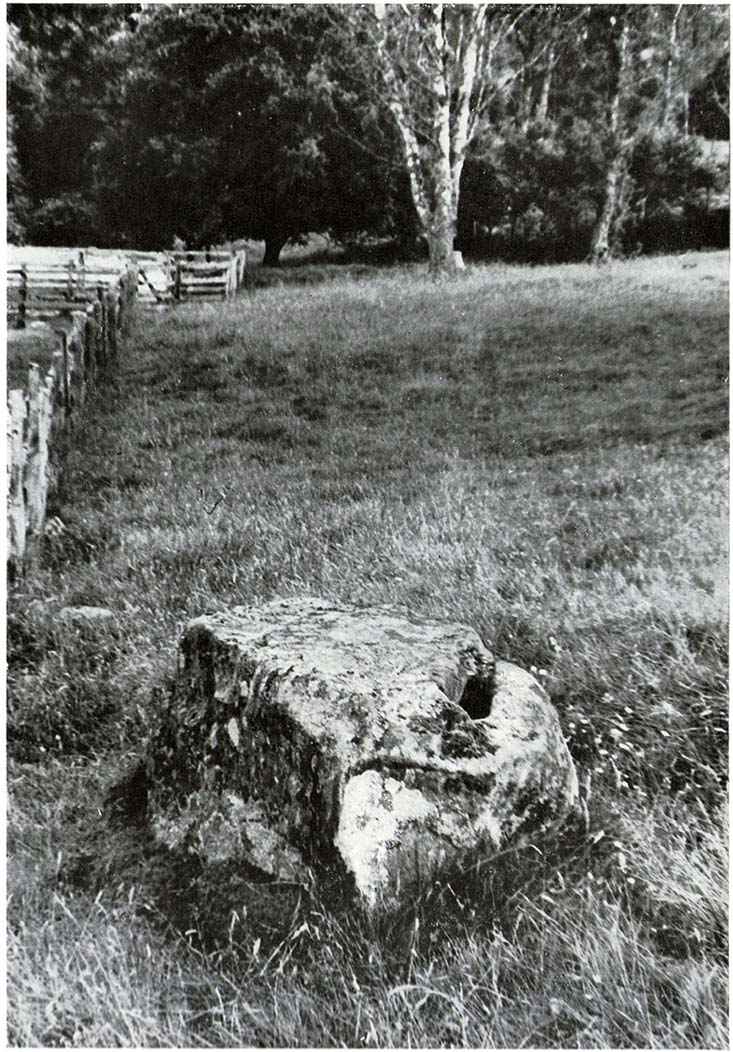

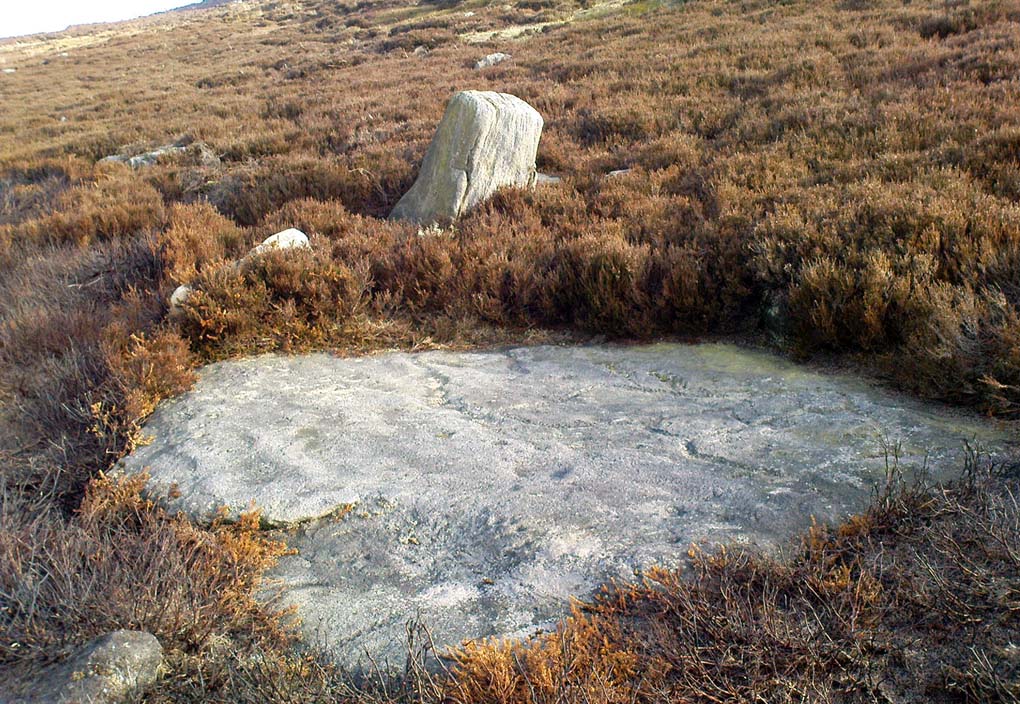

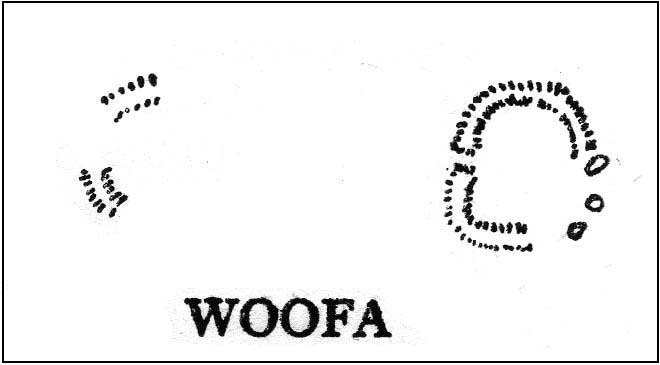

Things like ‘settlements’ and ‘enclosures’ are traditionally relegated by purist archaeologists to be little more than domestic or utilitarian sites: places where our ancestors kept cattle; or were used for defensive purposes; or lived for long periods of the year. Of course, these simple ideas are effective and true at some places; but here at Woofa Bank—in this particular enclosure—something more than just domestic activity was enacted, and over the period of many centuries by the look of things. We surmise this by the incidence of at least fifteen cup-and-ring stones being found within the enclosure itself; and at its very centre is a small standing stone, not previously recorded, that has perhaps five petroglyphs around it. The presence of such a large cluster of cup-and-ring stones close together within the enclosure would seem to suggest ritual activity.

One of the carvings at the centre of the enclosure (listed in the Boughey & Vickerman survey as Carving 372) has been suggested to represent a dancing human figure (the image here shows the anthropomorphic element), which it may well be. The incidence of this central stone and its surrounding petroglyphs has important magico-religious implications, relating it as a site used for creation myth narratives and repetitions (transpersonal explorations at this site may prove worthwhile). The wider extended enclosure with more petroglyphs contained inside it, suggest that additional ritual performances were enacted here; these may have had something to do with the cluster of prehistoric tombs scattered on the moorland plain 100 yards to the west, but we might never know.

It seems that the walled enclosure itself was constructed around the earlier cup-and-ring stones, probably many centuries later—but we need excavations here to give us more precise details. Much of the enclosure walling itself has the hallmarks of being late Bronze Age to Iron Age, whilst we know that prehistoric rock art can date back into the neolithic period; and from this period Eric Cowling (1946) reported that, at Woofa Bank, “at the western end of the ridge,” just above this enclosure, a neolithic flint site existed.

Cowling (1946) himself was one of very few archaeologists to even mention this impressive site, in a section exploring the “Iron Age” sites along Green Crag Slack at the eastern end of Ilkley Moor. He wrote:

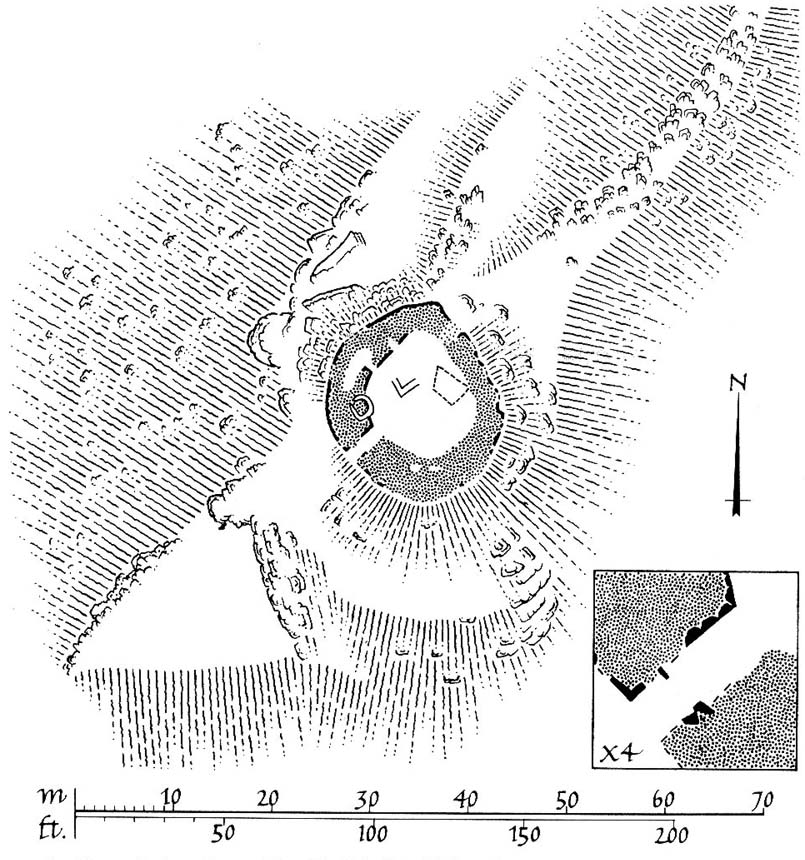

“At the other end of the site under the shadow of Woofa Bank and near the source of the Rushy Beck, is another D-shaped enclosure apparently unfinished. The plan is of a circle with a flattened side and does not exceed twenty-four yards across in any direction. Here the enclosing wall shows five or six courses at the lower end side and a simple entrance to the west.”

Though Cowling’s measurements are way out! The enclosure itself is much larger than he describes. For the most part, three-quarters of it give the impression of it being a large oval shape, but the design and outline of the walling changes on its southeastern side and kinks inward, in an arc, to eventually meet the walling in the middle eastern section. Its entire circumference measures approximately 220 yards all the way round; it is 65 yards across east-west; and about 61 yards north-south. The average height of the main walling is between 2-3 feet tall, and is made up of many large rocks, some of them positioned upright as standing stones, all packed together with earth and countless thousands of smaller stones. The walling itself is between 2-3 yards wide in many places and has two main entrances: one near the middle of the western wall and the other almost opposite to the east. The eastern entrance is marked by a standing stone between 3-4 feet tall. No gaps are visible at all on the northern curved section of the enclosure. On the overgrown southern edges, not all of the walling is visible and much of it is overgrown. On the whole it’s still very much as Cowling found it, with the arc of walling in this part of the enclosure difficult to make out clearly. There is also another line of walling that runs off to the east, beyond the main enclosure itself.

The clearer, more visible western line of walling, running south of the entrance on that side, has a large singular cup-and-ring stone laid right along its axis (carving 366 in the Boughey & Vickerman [2003] survey), a short distance before the walling changes direction east-west and runs along the bottom of the slope.

Folklore

Tradition tells that the tribal people from this site were involved in a battle with the Romans along this moorland plain.

…to be continued…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Chieveley 2001.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Eliade, Mircea, Images and Symbols, Harvill Press: London 1961.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Size, Nicholas, The Haunted Moor, William Walker: Otley 1934.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian