Cairn: OS Grid Reference – NS 8046 9916

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 47128

- Pendreich

From Bridge of Allan go down the main A9 road towards the University, but turn left up the Sheriffmuir road, 100 yards up turning right to keep you on track up the steep narrow dark lane, turning left at the next split in the road. Follow this for a mile or two all the way to the very end where the tell-tale signs of the unwelcoming english incomers of ‘Private’ now adorns the Pendreich farm buildings. There’s a dirt-track veering uphill diagonally right from here. Go up here and as it bends slightly left, look into the open copse of trees to the highest point here less than 100 yards to you right. That’s it!

Archaeology & History

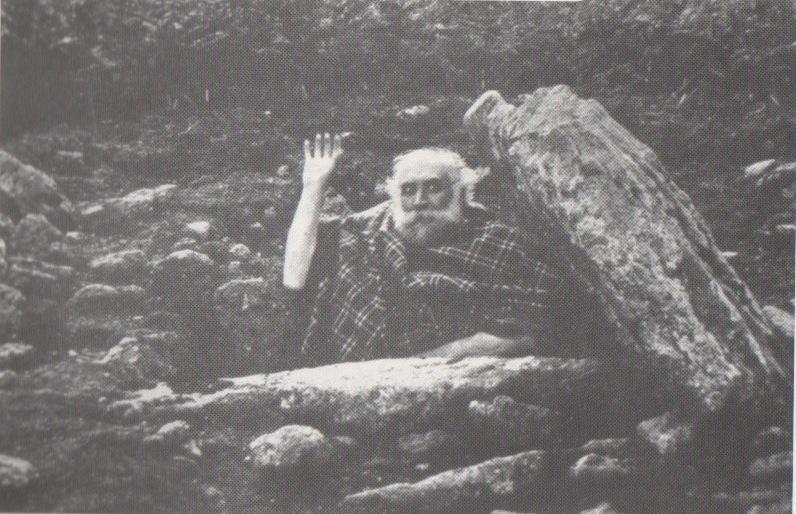

The remains of this prehistoric tomb sits right on the very crown of the hill round the back of Pendreich, covered on its western edges by old gorse bushes. Its eye speaks with the nearby sites of the Fairy Knowe to the south, the fallen standing stone of Pendreich Muir to the northeast, the associated cairns to the east, and the Pictish fortress of Dumyat behind them. When I came up here for the first time last week with local archaeologist Lisa Samson, we found that the land upon which the cairn now lives is fertile with a variety of edible (Boletus, Amanita, etc) and sacred mushrooms (Panaeolina, Psilocybes, etc). And, despite being told by locals and the archaeology record as a place where very little can be seen, I have to beg to differ.

The crowning cairn is of course much overgrown and has been dug into in earlier years, but just beneath the grassy surface you can feel and see much of the stone that constitutes this buried site. The cairn itself rises a couple of feet beneath the grass and is clearly visible as you walk towards it. At its edges there seems to be the fallen remains of a surrounding ring of stones. Inside of this ring we can see and feel the overgrown rocky mass and open cists sleeping quietly, awaiting a more modern analysis to tell us of its ancient past. When the site was visited by the Royal Commission lads in the 1960s, they went on to tell us the following about the place:

“This cairn is situated on the summit of a low knoll within a felled wood, 170 yards ENE of Pendreich farmhouse at a height of 600ft OD. It consists of a low, grass-covered mound which measures 40ft in diameter and stands to a maximum height of 1ft 6in. The surface is disfigured by pits caused in 1926 when the cairn was opened and three cists were uncovered. Two of these contained no relics; in the third there were fragments of bones and a broken beaker, some sherds of which are preserved in the Smith Institute, Stirling.”

Although we find the scattered remains of old farm equipment lying round the edge of this tomb, it’s still a good site to visit and, I’d say, worthy of further archaeological attention.

References:

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – 2 volumes, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1979.

- Watson, Angus, The Ochils – Placenames, History, Tradition, Perth & Kinross District Libraries 1995.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian