Cist: OS Grid Reference – NC 71455 62258

Also Known as:

Getting Here

Dead easy. From the top of the hill at Bettyhill, take the road east out of the village along the A836 Thurso road. At the bottom of the hill, on your left, you’ll see the white building of Farr church Museum. Walk to it and instead of going in the door, walk past it and round the back, or north-side of the church where, up against the wall, you’ll see this small stone-lined hole in the ground. Y’ can’t really miss it.

Archaeology & History

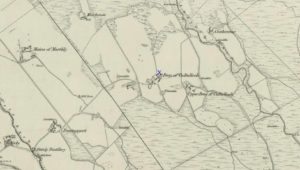

Originally located 7½ miles (12.1km) to the south at Chealamy (NC 7240 5017), in the prehistoric paradise of Strathnaver, it was uncovered following road-building operations in 1981 and, to save it from complete destruction, was moved to its present position on the north-side of Farr church museum. It was fortunate in being saved, as it was covered by a large boulder which the road operators tried to smash with a large jack-hammer; but in breaking it up, they noticed a hole beneath it. Thankfully, old Eliot Rudie of Bettyhill—a well respected amateur historian and archaeologist in the area—was driving past just as it had been uncovered by the workmen. He recognised it as being a probable cist and so further operations were stopped until it was investigated more thoroughly.

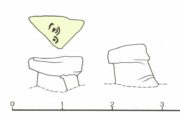

The cist—measuring some 4 feet long by 3 feet wide and about 1½ feet deep—contained the burial of what was thought to be a man in his mid- to late-twenties. The remains were obviously in very decayed state and it was thought by archaeologist Robert Gourlay (1996), that the body itself had been “deposited in the grave (when it was) in an advanced state of decomposition.” Also in the cist they found a well-preserved decorated beaker, within which Gourlay thought “probably contained some kind of semi-alcoholic gruel for the journey of the departed to the after-life.”

References:

- Gourlay, Robert, Sutherland – An Archaeological Guide, Birlinn: Edinburgh 1996.

- Gourlay, Robert B., “A Short Cist Beaker Inhumation from Chealamy, Strathnaver, Sutherland”, in Proceedings Society Antiquaries Scotland, volume 114, 1984.

- Gourlay, Robert & Rudie, Eliot, “Chealamy, Strathnaver (Farr) Beaker Cist”, in Discovery Excavation Scotland, 1981.

Acknowledgments: To that inspiring creature Aisha Domleo, for her bounce, spirit and madness to get me up here; and for little Lara too, for meandering to the church museum where this cist can be seen; and to Eliot Rudie, who pointed it out to us.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian