Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – NO 18474 01656

Also Known as:

- Scotlandwell

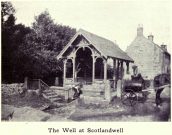

Whichever way you come into the hamlet—be it along the A911 from either Milnathort or Glenrothes, or up the B920 from Ballingry side—the only little carpark to use is about 20 yards from the main road junction, on the west-side of the road, appropriately named Well Road. The site is unmissable beneath the small well-house at the end of this short cul-de-sac.

Archaeology & History

When a village is named after a well, you know that its waters held some considerable importance! Mentioned as early as 1218 as “de fonte Scotie” and subsequently many variations thereof in centuries thereafter, the place-names authority Simon Taylor (2017) thinks it may have been mentioned as early as 1090 CE.

Although there has never been a direction dedication of the Scotland Well to any saint, as J.M. MacKinlay (1904) and others have pointed out, in the village itself was an ancient medieval hospital that belonged to “the Trinity or Red Friars” that was built for the benefit of the poor by the Bishop of St. Andrews, some 22 miles to the east. The hospital was at first dedicated to St. Thomas and subsequently to the Virgin, or St Mary. Holy wells dedicated to both saints are renowned the world over as having great medicinal properties, but no extant written document relates either saint to the well.

Folklore

The main reason for this site maintaining such an honourable place in Scottish history is its association with the two great Scottish heroes, Sir William Wallace and King Robert the Bruce. In the pseudonymous Historica’s (1934) literary rambles, he told that, after coming down out of the Lomond Hills,

“We descend the narrow defile—the Howgate—into Scotlandwell—Fons Scotia—famous for its medicinal springs, where tradition says King Robert the Bruce came to take the waters for scrofula and leprosy in 1295. The great Sir William Wallace—according to ‘Blind Harry’—also has associations here. His famous swim to the Castle Island, for a boat to take over some of his men to capture the english on St. Serf’s, took place from below Scotlandwell.”

In Ruth & Franks Morris’ (1982) fine survey of Scottish wells, they told that upon their visit to the Scotland Well, three people they met still thought highly of its curative properties. “Of these three people,” they said,

“one was a sufferer from cancer which was the cause of a painful skin rash. He had been persuaded to try the water and found that it did him so much good that he was driven from Edinburgh to the well, a round trip of some 80 miles, at at regular intervals to drink the water and take back with him two demi-johns of it.”

According to the man concerned, it did him the world of good and cleared the stubborn body rash he’d been suffering!

References:

- Day, J.P., Clackmannan and Kinross, Cambridge University Press 1915.

- Historicus, Historic Scenes within our Limits, Kinross-shire Advertiser: Kinross 1934.

- MacKinlay, James M., Influence of the Pre-Reformation Church on Scottish Place-Names, William Blackwood: Edinburgh 1904.

- Morris, Frank & Ruth, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Taylor, Simon, The Place-Names of Kinross-shire, Shaun Tyas: Donington 2017.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks for being able to use the 1st edition OS-map for this site profile, Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian