Standing Stone (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SK 5779 0644

Also Known as:

-

Little John’s Stone

Archaeology & History

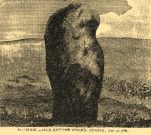

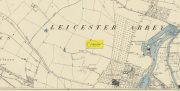

This once impressive megalithic site was first mentioned in 1381, giving its name to the field Johnstone Close. Shown on the early Ordnance Survey maps standing on a raised portion of land in an area north of the modern town centre, not far from the Abbey, its destruction had been a slow one until it finally disappeared about a hundred years ago. One of the early descriptions of it was by John Nichols (1804) in his immense series of works on the county. He called it ‘Little John’s Stone’* and gave us the first known illustration of the monolith (right), telling it to be “7 feet 2 inches high, and 11 feet 3 inches wide”—although he obviously meant circumference and not ‘wide’, as his illustration clearly shows. Although this slight error was perhaps the reason that Historic England proclaimed the stone to have been little more than “a natural feature”—which it clearly wasn’t.

The stone stood in what Nichols called “a kind of amphitheatre”, and what James Hollings (1855) subsequently called a sloping hollow which, he thought, had “been excavated by the hand of man.” It was located “in a meadow, a little to the west of the Fosse-way,” he said, “not far from the ancient boundary wall of the Abbey of St. Mary de Pratis.” There’s little doubt it was a prehistoric standing stone. Hollings described it as standing erect and told it to be one of those “monolithic erections, or hoar stones, anciently sanctified by the rites of Druidic worship,” comparing it to “similar rude columns” in Cornwall, Scotland and just about everywhere! He also told that it was a place of summer solstice gatherings, being

“in the memory of many living, annually visited about the time of Midsummer by numerous parties from the town in pursuance of a custom of unknown antiquity.”

When James Kelly (1884) wrote about the stone, little was left of it save at ground level. He repeated much of what Hollings had previously written, but had a few notes of his own. One related to the local mayor and MP for Leicester, Mr Richard Harris, dated January 1853, who told him:

“When a boy, he had frequently played on the spot where it was customary for the children to resort to dance round the stone (which he thought was about eight feet high), to climb upon it and to roll down the hill by which the stone is in part, encircled. The children were careful to leave before dark, as it was believed that at midnight the fairies assembled and danced round the stone.”

More than fifty years later when Mrs Johnson (1906) wrote about the place she said that only a small section of the stone still remained, just “a few inches above the earth.” It had been incrementally “broken to pieces down to the surface of the ground and used to mend the road.” (Kelly 1884) Alice Dryden (1911) lamented its gradual demise in size, summarizing:

“At the beginning of the nineteenth century it was about 7 feet high, but by the year 1835 it had become reduced to about 3 feet. In 1874, according to the British Association’s Report, it was about 2 feet high, and it has now completely disappeared.”

Local tradition tells that some small pieces of St John’s Stone were moved to the nearby St. Luke’s church, where bits of it can still be seen. Has anyone found them?

More recent lore has attributed St John’s Stone to have been aligned with the Humber Stone (SK 62416 07095) nearly 3 miles to the east, in a summer solstice line—but it’s nowhere near it! A similar astronomical attempt said that the two stones lined up with the Beltane sunrise: this is a little closer, but it still doesn’t work. The equinox sunrise is closer still, but whether these two stones were even intervisible is questionable.

* this was probably the name it was known by local people who frequented the nearby Robin Hood public house (long gone); its saintly dedication being less important in the minds of Leicester’s indigenous folk.

References:

- Cox, Barrie, The Place-Names of Leicestershire – volume 1, EPNS: Nottingham 1998.

- Devereux, Paul, “The Forgotten Heart of Albion,” in The Ley Hunter, no.66, 1975.

- Dryden, Alice, Memorials of Old Leicestershire, George Allen & Sons: London 1911.

- Hollings, James Francis, Roman Leicester, LLPS: Leicester 1855.

- Kelly, William, Royal Progresses and Visits to Leicester, Samuel Clarke: Leicester 1884.

- Nichols, John, The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire – volume 3: part 2, J. Nichols: London 1804.

- Johnson, T. Fielding, Glimpses of Ancient Leicester, Clarke & Satchell: Leicester 1906.

- Trubshaw, Bob, Standing Stones and Markstones of Leicestershire, Heart of Albion Press 1991.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian