Cup-Marked Stones (lost): OS Grid Reference – SE 9657 8840

Archaeology & History

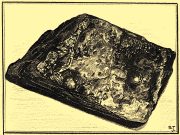

In the autumn of 1848, antiquarian John Tissiman (1850) and his associates took to uncovering two burial mounds amidst a large cluster of them on the eastern edge of West Ayton Moor. This one at Way Hagg was quite a big fella, measuring 36 yards across. When they cut into its northern edge towards the centre, 8-10 feet in, they came across an upright stone, nearly two feet high, on which five cup-marks had been cut. (see sketch, no.2) Slightly beyond this were three other stones (in sketch, nos.1, 3 & 4), each with cup-marks on them, beneath which was a tall urn. Whether or not the carvings had been deliberately positioned to cover the urn, we do not know. Nonetheless, we can be reasonably assured that these petroglyphs had some mythic association with death when they were placed here.

Tissiman gave us the following detailed measurements of the respective carvings:

“1: Nearly even surface. Length, from 16 to 18 inches; breadth, 10 to 20 ditto; depth, 8 to 9 ditto; with large oval hole cut in the centre, 7½ inches long, 4 inches broad, and 3½ inches in depth. On the opposite side are three holes, from 2 to 3 inches in diameter, and from 1 inch to 1½ deep. 2: Uneven surface. Length, 23 inches; breadth, 14 inches; depth, 13 inches; with five holes, from l½ to 3½ inches in diameter, and 1 to 1½ inches in depth. 3: Uneven surface. Length, 33 inches; breadth, 22 inches; depth, 10 inches, with four holes, the largest being 4½ inches in diameter and 3 inches deep; the others, from 1½ inches to 2 inches in diameter, and 1 to 1½ inches deep. 4: Uneven surface. Length, 27 inches; breadth, 23½ inches; depth, 10 inches, with 13 holes, from 1½ inches to 5 inches in diameter, and ¾ of an inch to 3 inches in depth; also three lines at the end of the stone.”

The carvings were included in Brown & Chappell’s (2005) fine survey, but they weren’t able to find out what happened to them after Tissiman’s excavation. They remain lost. If anyone has any information as to where they might be, please let us know.

References:

- Brown, Paul & Chappell, Graeme, Prehistoric Rock Art in the North York Moors, Tempus: Stroud 2005.

- Tissiman, John, “Report on Excavations in Barrows, in Yorkshire,” in Journal British Archaeological Association, April 1850.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian