Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 13891 45757

Also Known as:

- Carving no.199 (Hedges)

From Ilkley, take the same directions to reach the Haystack Rock; then walk east along the edge of the moor, past the Pancake Stone and keep along the footpath for more than 800 yards till you see the large cairn above-right of the footpath by about 20 yards, a short distance before you’d hit the Rushy Beck. Walk to the cairn, and past it onto the moor for another 30-40 yards, checking the rocks on the ground thereby. You’ll find it!

Archaeology & History

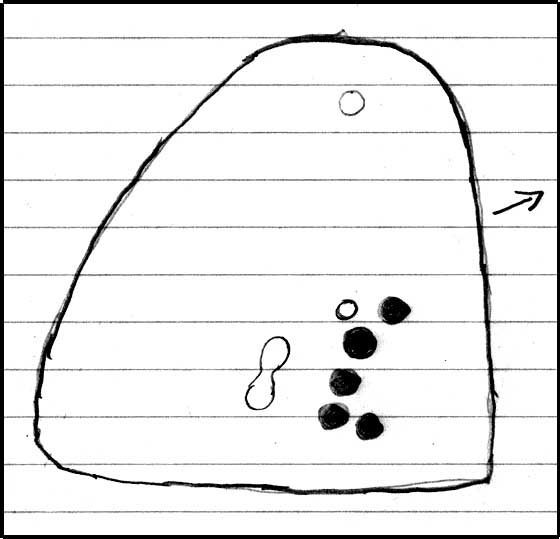

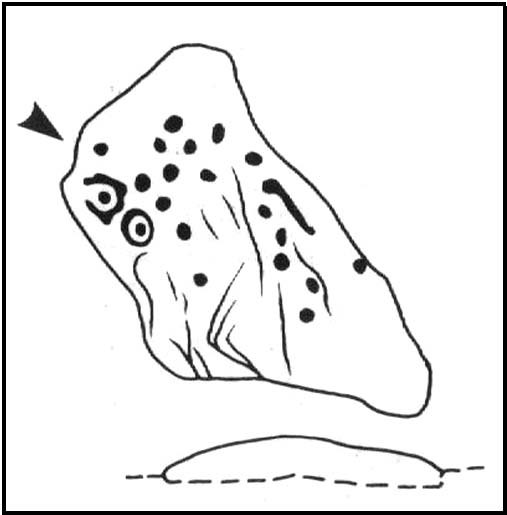

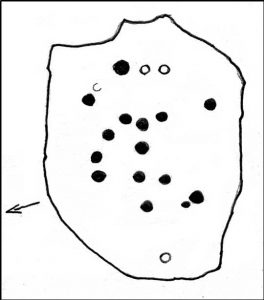

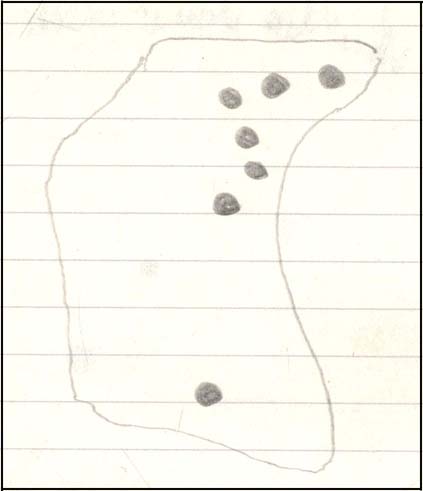

Described in John Hedge’s (1986) survey as a “long, low, smooth grit rock, partly covered with heather. Seven clear cups”, we first found this carving when we were out bimbling on one of our hundreds of ventures on these moors as kids—on this occasion, as I recall, seeking out a cup-and-ring stone that Stuart Feather discovered and mentioned in an early Yorkshire Archaeology Journal. Less than a yard away from the one which Mr Feather described (the overgrown cup-and-ring stone no.375) was this curvaceous female rock, with seven simple cup-markings, mostly on its northeastern side.

When the heather is low in this area, you can clearly make out extensive remains of prehistoric walling 11 yards east of the cup-marked stone, running north-south. This eventually meets up with another line of walling that runs east-west and bends back around on the western sides of the carving about 20 yards away, seemingly encircling it. This enclosure will be described in greater detail at a later date.

References:

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian