Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NT 65858 99107

Also Known as:

- Pump Well

Archaeology & History

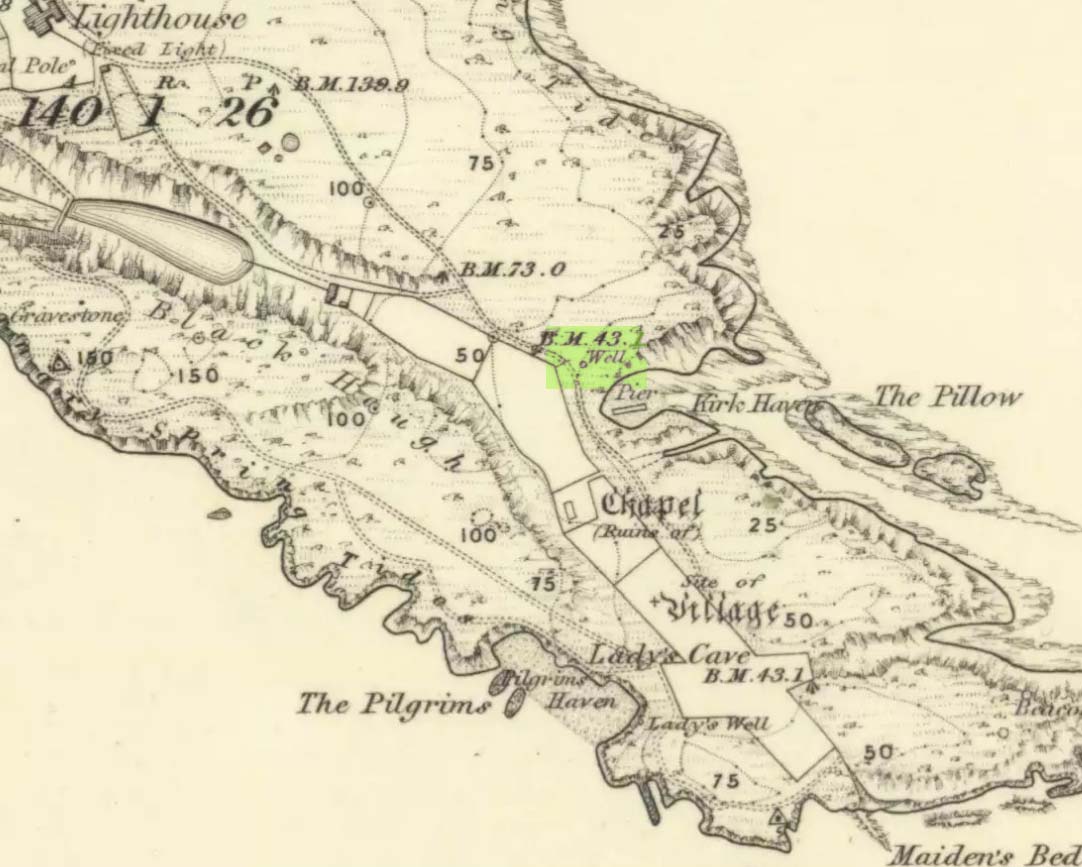

This seems to be the only ‘St John’ dedication on the Isle of May: a small island littered with more saint’s names, seemingly, than Iona and Lindisfarne combined! Illustrated on the 1855 OS-map, without name—and on the present-day large-scale OS-maps too, 20 yards or so from its 1855 position—the standard archaeo-historical records say nothing of the place. Thankfully antiquarian and folklore accounts have preserved evidence of its title. When the Victorian traveller Thomas Muir (1868; 1883) visited the Isle of May, he told how the islanders struggled to maintain a good water supply during a drought there in the 1860s. St. John’s Well was, he told,

“A pump standing by the path above Kirk Haven. The water good, but a little brackish. During all the drought of this summer we pumped water out of this well to supply our cattle.”

After Æ. J.G. Mackay’s (1896) visit to the island he told that here, along with the other holy wells on May,

“their brackish waters have lost the magic virtue they were credited with in early christian, possibly in pagan times.”

In more recent times it was described in W.J. Eggeling’s (1985) natural history survey. St. John’s Well was,

“the well within the high, cylindrical, whitewashed wall-surround lying across Haven Road from the Coal House. Also known as the Pump Well. It is a guiding mark for boats entering Kirk Haven.”

Folklore

St. John’s Day (June 24) was the christian name given to the traditional Midsummer Day, or days, around which good heathen festivals occurred; but we can find no ritual accounts of activity specific to this Well. Help!

References:

- Dickson, John, Emeralds Chased in Gold; or, The Isles of the Forth, Oliphant: Edinburgh 1899.

- Eggeling, W.J., The Isle of May, Lorien 1985.

- Mackay, Æ. J.G., A History of Fife and Kinross, William Blackwood: Edinburgh 1896.

- Muir, Thomas S., The Isle of May – A Sketch, Edinburgh 1868.

- Muir, Thomas S., Ecclesiological Notes on some of the Islands of Scotland, David Douglas: Edinburgh 1883.

- Simpkins, John Ewart, Examples of Printed Folk-lore Concerning Fife, with some Notes on Clackmannan and Kinross-shires, Sidgwick & Jackson: London 1914.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian