Cup-Marked Stone (lost): OS Grid Reference – SE 2556 4687

Also Known as:

- Carving no.556 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Archaeology & History

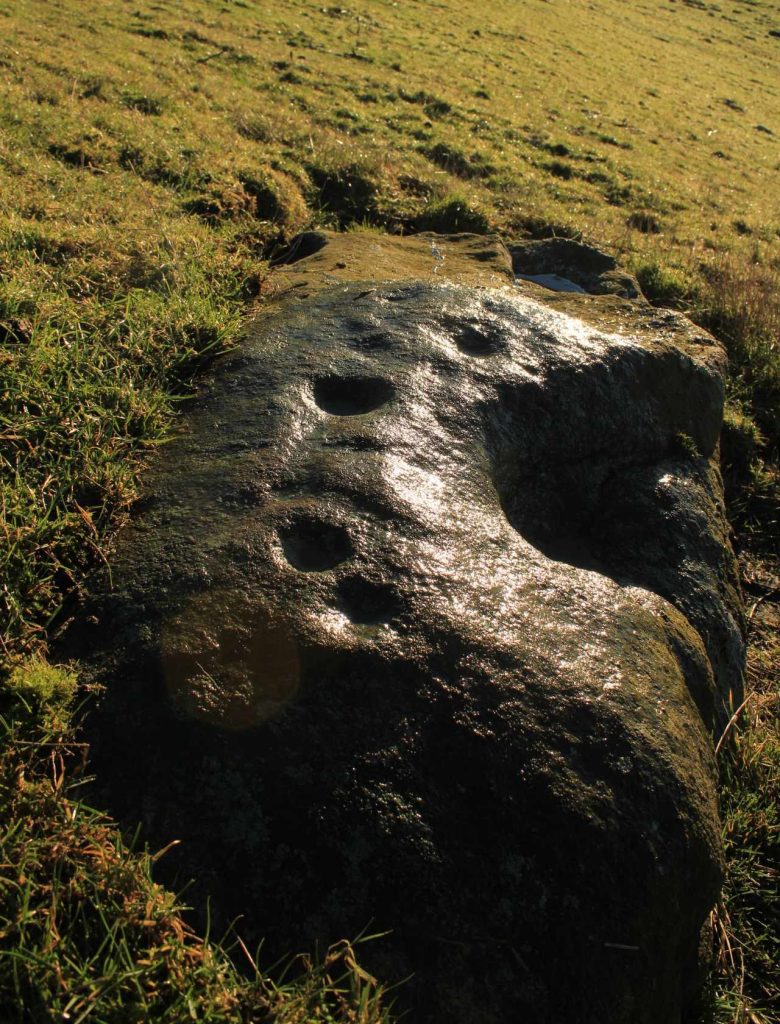

We know very little about this carving, which was first highlighted on Eric Cowling’s (1940) map of Wharfedale petroglyphs. Described simply as one of the “cup-marked rocks”, he mentioned it briefly in Rombald’s Way (1946) as being “the most easterly carving” in mid-Wharfedale—which it was at the time (a very recent find by Benn Potts of a cup-marked stone at Weeton has pushed the boundary further eastwards). Oddly for Cowling, he left no further notes nor sketch of the carving and when Stuart Feather (1961) came to write of it, he merely copied Cowling’s earlier words. It’s not been seen since. In Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) survey, they could find no cup-marked stone in the wood but thought instead that,

“this may be due more to confusion than to loss of the carving. Riffa Wood does contain a carving: of a Native American on a conspicuous rock alongside one of the many woodland paths. Furthermore, one or two local residents recall a German prisoner carving something on a rock in Riffa Wood during the Second World War. Presumably, this is the origin of the Native American carving. Could it be that this man added something of his own to what was already a carved rock, in which case the Native American as he now appears is the site noted by Cowling before the War?”

No cup-marks exist on this Native American carving, and it’s highly unlikely that Cowling would have made such an elementary mistake. The carving no doubt lies covered in woodland vegetation waiting, once more, for the day that someone comes along and exposes its visage to the world again. Let us know if you manage to find it…

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Cowling, E.T., ‘A Classification of West Yorkshire Cup and Ring Stones,’ in Archaeological Journal, volume 97, 1940.

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way: A Prehistory of Mid-Wharfedale, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Feather, Stuart, “Mid-Wharfedale Cup-and-Ring Markings,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, volume 6, no.3, March 1961.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian