Hillfort (destroyed): OS Grid Reference –TQ 4383 8510

Archaeology & History

Uphall Camp, 1893

This prehistoric site was a giant – a huge colossus of an ‘enclosure’, a ‘settlement’, a ‘camp’—call-it-what-you-will. More than a mile in circumference and with an internal area of 48 acres (big enough to hold 37 football fields!), archaeologist Pamela Greenwood (1989) told us, not only that it was “the largest recorded hillfort in Essex”, but that it compared in size with the immensity of Maiden Castle in Dorset! Yet despite it being cited by the Oxford Archaeology report of Jonathan Millward (2016) as “the most significant archaeological site within the Borough” from the Iron Age period, it has fallen prey to the thoughtless actions of the self-righteous Industrialists who, as usual, have completely destroyed it. It was already in a “bad” state when the Royal Commission lads visited here around 1916, saying how it was “in some danger of destruction.” Thankfully, in earlier centuries, we did have more civilized and educated people who seemed proud to describe what there was of their local history.

Early literary accounts seem sparse; although in Mr Wright’s (1831) huge commentary to Philip Morant’s (1768) Antiquities of Essex, he thought that the adjoining parish of Barking—whose ancient boundary line is marked here by the southern embankments of the enclosure—derived from the Saxon words burgh-ing, which he transcribed as ‘the fortress in the meadow’. The same derivation was propounded in Richard Gough’s 1789 edition of Camden’s Britannia, from the “Fortification in the meadows.” It seems a more reasonable derivation than that ascribed in the Oxford Names Companion (2002) as the “(settlement of) the family or followers of a man called *Berica” (the asterisk here denotes the fact that no personal name of this form has ever been found and is pure guesswork). But according to the English Place-Name Society text on Essex by Paul Reaney (1935), the early spellings of Barking implies a derivation from ‘birch trees.’ Anyway….

Uphall Camp c.1735

A fine plan of the site was drawn by John Noble some time around 1735 although, curiously, he seems to have written no notes about the place. The first real citation of Uphall Camp as an antiquity seems to have been by Morant himself (1768). In a work bedevilled by genealogical and ecclesiological tedium, he occasionally breaks from that boredom to tell of the landscape and the people living here, mentioning our more ancient monuments—but only in passing, as illustrated here:

“Near the road leading from Ilford to Berking, on the north west side of the brook which runs across it, are the Remains of an ancient Entrenchment: one side of which is parallel with the lane that goes to a farm called Uphall; a second side is parallel with the Rodon, and lies near it; the third side looks towards the Thames; the side which runs parallel with the road itself has been almost destroyed by cultivation, though evident traces of it are still discernible.”

Just over thirty years later we were thankfully given a more expansive literary portrayal by Daniel Lysons. (1796) Lysons was drawing some of his material from a manuscript on the history of Barking by a Mr Smart Lethieullier, written about 1750 (this manuscript was unfortunately destroyed by fire, and no copies of it ever made). He told us:

“In the fields adjoining to a farm called Uphall, about a quarter of a mile to the north of Barking-town, is a very remarkable ancient entrenchment: its form is not regular, but tending to a square; the circumference is 1792 yards, (i.e., one mile and 32 yards,) inclosing an area of forty-eight acres, one rood, and thirty-four perches. On the north, east, and south sides it is single trenched: on the north and east sides the ground is dry and level (being arable land), and the trench from frequent ploughing almost filled up: on the south side is a deep morass: on the west side, which runs parallel with the river Roding, and at a short distance from it, is a double trench and bank: at the north west corner was an outlet to a very fine spring of water, which was guarded by an inner work, and a high keep or mound of earth. Mr. Lethieullier thinks that this entrenchment was too large for a camp: his opinion therefore is, that it was the site of a Roman town. He confesses that no traces of buildings have been found on that spot, which he accounts for on the supposition that the materials were used for building Barking Abbey, and for repairing it after it was burnt by the Danes. As a confirmation of this opinion, he relates, that upon viewing the ruins of the Abbey-church in 1750, he found the foundations of one of the great pillars composed in part of Roman bricks. A coin of Magnentius was found also among the ruins.”

But this is a spurious allusion; albeit an understandable one when one recognizes that the paradigm amongst many writers at the time was to say that anything large and impressive was either a construction of the Romans or the Danes, as the early British—it was deemed—were incapable of building such huge monuments. How wrong they were!

In Mrs Ogborne’s (1814) description of Uphall Camp, she thought that its form and character betrayed anything Roman and—although she wasn’t specific—seemed to prefer the idea that our earliest Britons had built this place. And she was right! She wrote:

“There is, about a quarter of a mile from Barking, adjoining Uphal farm, on the road to Ilford, an antient entrenchment, a mile and 32 yards in circumference, with the corners rounded off; the west side, parallel with the river Rodon, has a double trench and bank, and a high keep, or mound of earth, about 94 yards round the base, about nine in height, on the side of the river, and seven on the opposite side: there was an outlet to a spring of water at the north-west corner; the south side has a morass; the north and east sides are single trenched, which is almost lost by cultivation, and in some places barely discernible.”

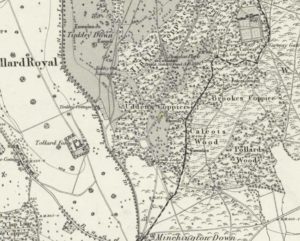

Uphall Camp on 1873 map

Uphall Camp on 1897 map

When the Ordnance Survey lads gave the site their attention in the 1870s, they showed its real size for the first time—cartographically at least! As the two old maps either side here show, it was a big one! Although some sections of the edges of the ‘camp’ were diminishing at the time, much of it was still in evidence. And when the local writer Edward Tuck (1899) wrote about it, he told us,

“On the north and east sides the ground is dry and level (being arable land) and the trench from frequent ploughings is almost filled up. On the south side is a deep morass; on the west side which runs parallel with the river Roding, and at a short distance from it is a double trench and bank; at the north-west corner is an outlet to a very fine spring of water, which is guarded by an inner work and a high keep or mound of earth designated “Lavender Mound.” Mrs. Ogborne in her History of Essex gives a charming drawing of this mound as it was in 1814, and says that the mound was then about 94 yards round the base, and about nine yards in height, with trees growing upon it, and its surface covered with soft verdure.”

Uphall earthworks in 1893

Several other writers mentioned the remaining embankments of Uphall Camp, which was beginning to fade fast as the city-builders spread themselves further afield. A chemical factory did most of the damage (as they still do, in more ways than one!). When the Royal Commission (1921) lads came here they curiously deemed it as an “unclassified” structure; but in those days unless things were Roman in this neck of the woods, it could unduly puzzle them! Their account of it told that,

“the remaining earthworks consist of a short length of rampart with an irregularly shaped mound at the north end, which is known locally as Lavender Mount, and another short length north of the farmhouse; there are also traces of the east side of the camp running parallel with Barking Lane. An early plan shows part of the north and east sides of the earthwork and suggests that it was roughly rectangular in outline. In 1750 the north, east and south sides are said to have had a single trench, and the west side a double trench and bank.

“The mound is 21 ft. high and 85 ft. in diameter at the base. The date of the earthwork is doubtful, but it does not appear to be pre-Roman.”

1908 photo of Lavender Mount

1814 sketch of Lavender Mount

The ‘Lavender Mount’ aspect in this monument, seemed a peculiar oddity. Even modern archaeologists aren’t sure of what it might have been, erring on the side of caution with interpretations saying it was a keep of some sort, or a small beacon hill. It might have been of course; but if it was a beacon hill, there would very likely be some written account of it – but none exist as far as I’m aware. Initial impressions when just looking at the images is that it was a tumulus, but the position of the mound on top of the raised earthen embankments tells us that it was constructed after the Iron Age ramparts. Writers of the Victoria County History (1903) said the same, suggesting a Saxon or more likely Danish origin. The area around Lavender Hill was eventually explored by archaeologists in 1960, and several times thereafter – and what they uncovered showed us a continuity of usage that spanned several thousand years!

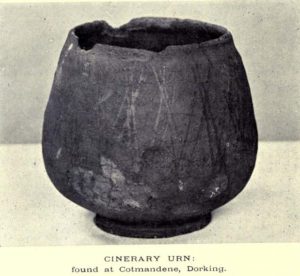

The 1960 excavation took place where, adjacent to the embankment, “the bank and ditch contained middle-Iron Age pottery”, along with traces of the large wooden fencing-posts (palisade) that initially surrounded and protected the enclosure. In Pamela Greenwood’s (1989) archaeological report, she told us that in further digs in 1983-4 there were discoveries of neolithic and Bronze Age flint remains. The finds included,

“a leaf-shaped arrowhead and a discoidal scraper… fragments of an Ardleigh type urn, probably from a middle Bronze Age burial disturbed by later activity. An L-shaped ditch, possibly part of an enclosure or field boundary, was found during the watching-brief. It contained flint-gritted pottery, perhaps attributable to the Bronze Age.”

But the majority of the finds at Uphall came from the mid-Iron Age period. Greenwood continued:

“The settlement, judging from the relatively small area of the fortification actually excavated, was laid out in a regular way. As might be expected, the round-houses appear to be aligned, indicating some sort of street-pattern. ‘Four-poster’ structures have been located in particular areas, again pointing to some sort of designation of special zones of activity. Large quantities of charred grain from the post-pits and surroundings would confirm that these structures are granaries….

“The middle Iron Age structures are of several types: round-houses or round-buildings, pennanular enclosures, (wooden) ‘four-posters’; rectangular structures, ditches, post-holes and innumerable and ill-assorted small pits, small gullies and holes dug into the gravel. Many of the last three types are undatable and could belong to the Iron Age, Roman, medieval or later activity on the site.”

I could just copy and paste the rest of Greenwood’s report here, but it’s quite extensive and interested readers should refer to her own account in the London Archaeologist . It’s a pity that it’s been destroyed.

References:

- Crouch, Walter, “Ancient Entrenchments at Uphall, near Barking, Essex,” in Essex Naturalist, volume 7, 1887.

- Crouch, Walter, “Uphall Camp,” in Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, volume 9 (New Series), 1906.

- Doubleday, H.A. & Page, William (eds.), Victoria History of the County of Essex – volume 1, Archibald Constable: Westminster 1903.

- Greenwood, Pamela, “Uphall Camp,” in Essex Archaeology & History News, 1987.

- Greenwood, Pamela, “Uphall Camp, Ilford, Essex,” in London Archaeologist, volume 6, 1989.

- Hanks, Patrick, et al, The Oxford Names Companion, Oxford University Press 2002.

- Hogg, A.H.A., British Hill-Forts: An Index, BAR: Oxford 1979.

- Kemble, James, Prehistoric and Roman Essex, History Press: Stroud 2009.

- Lysons, Daniel, The Environs of London – volume 4, T. Cadell: London 1796.

- Millward, Jonathan, London Borough of Redbridge: Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal, Oxford Archaeology 2016.

- Morant, Philip, The History and Antiquities of Essex – volume 1, T.Osborne: London 1768.

- Norris, F.J., “Uphall Camp”, in Gentleman’s Magazine, 1888.

- Ogborne, Elizabeth, The History of Essex, Longmans: London 1814.

- Reaney, Paul, The Place-Names of Essex, Cambridge University Press 1935.

- Royal Commission Ancient & Historical Monuments, England, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex – volume 2, HMSO: London 1921.

- Tuck, Edward, A Sketch of Ancient Barking, Its Abbey, and Ilford, Wilson & Whitworth: Barking 1899.

- Wilkinson, P.M., “Uphall Camp,” in Essex Archaeology & History, volume 10, 1979.

- Wright, Thomas & Bartlett, W., The History and Topography of the County of Essex – volume 2, G. Virtue: London 1831.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian