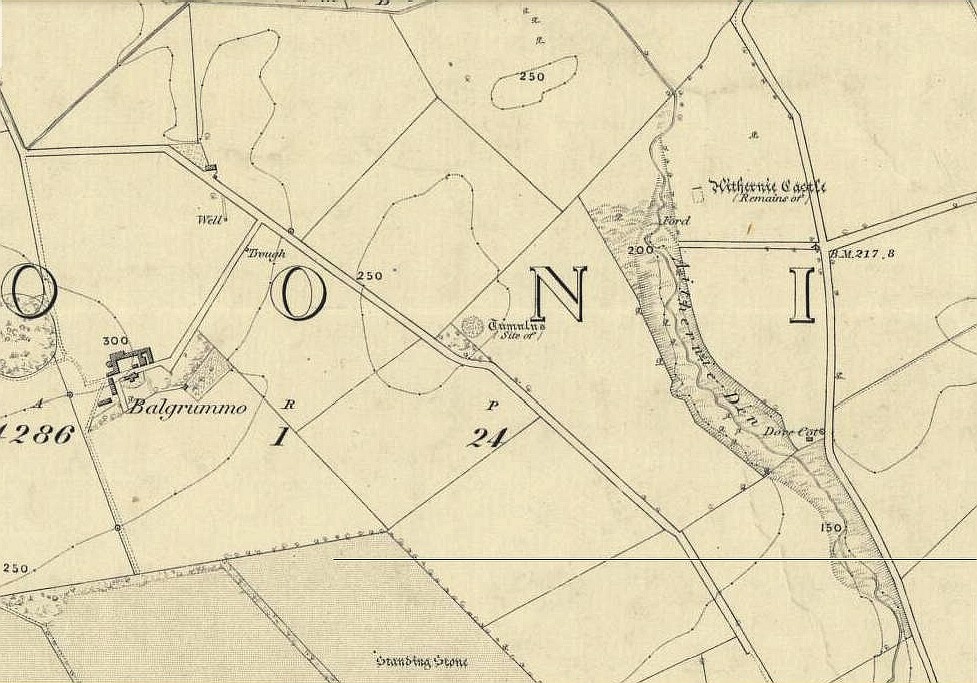

Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – NN 7607 4294

Also Known as:

From Kenmore, take the minor road on the south-side of Loch Tay for 1½ miles (2.4km) until you reach the hamlet of Acharn. From here take the track uphill for ½-mile past the Acharn waterfalls and when you come out on the east-side of the trees, keep walking uphill parallel to the trees and burn until the land levels-out and the track heads away, east. 200 yards ahead, on the left-side of the track, you’ll see the large fairy-mound.

Archaeology & History

First reported in archaeological circles in the Discovery & Excavation Scotland mag in 1964, this archetypal fairy-mound or tumulus sitting on the grassy plain overlooking the eastern end of Loch Tay and district would have been known of by local people in older times, but I can find no early accounts of it, nor its traditions. When Bob Money (1990) came here, he told of the grand vista stretching into the distant mountains:

“From here the views…are superb, and the little mound, which is an ancient tumulus, or burial mound, has sat here undisturbed for several thousand years, guarding the secret of its once important occupant.”

Circular in structure and measuring 20 feet across, the mound rises nearly four-feet high and is probably Bronze Age in origin. Although mostly covered in grass, there are some loose stones visible on the side of the mound, seeming to indicate that it may be a covered cairn. No excavation have yet taken place here.

References:

- Money, Bob, Scottish Rambles – Corners of Perthshire, Perth 1990.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the unholy bunch who helped travel, locate, photograph and take notes on the day of our visit here, including Aisha, Lara & Leo Domleo; Lisa & Fraser; Nina and Paul. Let’s do it again and check out the unrecorded stuff up there next time!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian