Chambered Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SH 50761 70185

Also known as:

- Bryncelli Ddu

Archaeology & History

An excellent passage grave tomb that’s been described by many historians over the last two hundred years, and was subject to a fine excavation in the first half of the 20th century. Ascribed as neolithic in origin, recent finds of human activity on the edge of the surrounding henge indicates people have been “up to things” hereby since at least 6000 BC. Deriving its name from “the mound of the black grove,” the site as we see it today has been much restored and is so different to when it was visited by Thomas Pennant and other antiquarians.

According to an anonymously written essay in Archaeologia Cambrensis in 1847, the site was first described by Henry Rowlands (1723) where, in relation to another site, he told were,

“the remains of two carnedds, within a few paces of one another: the one is somewhat broken and pitted into on one side, where the stones had been carried away; the other having had its stones almost all taken away into walls and hedges, with two standing columns erected between them.”

A somewhat more detailed description came from Thomas Pennant a few years later. He wrote:

“A few years ago, beneath a carnedd similar to that at Tregarnedd, was discovered, on a farm called Bryn-celli-ddu…a passage three feet wide, four feet two or three inches high and about nineteen feet and a half long, which led into a room about three feet in diameter and seven in height. The form was an irregular hexagon, and the sides composed of six rude slabs, one of which measured in its diagonal eight feet nine inches. In the middle was an artless pillar of stone, four feet eight inches in circumference. This supports the roof, which consists of one great stone near ten feet in diameter. Along the sides of the room was, if I may be allowed the expression, a stone bench, on which were found human bones, which fell to dust almost at a touch: it is probable that the bodies were placed on the bench… The diameter of the incumbent carnedd is from ninety to a hundred feet.”

But the main excavation work at Bryn Celli Ddu was done in the late-1920s by W.J. Hemp (1930) and his team, who, as usual following such digs, ended up with just as many questions about the site as they had answers! One of the best descriptions of Hemp’s excavation work was by W.F. Grimes (1932) in an essay he wrote for the East Anglian Prehistoric Society where he gave the following detailed description of the finds:

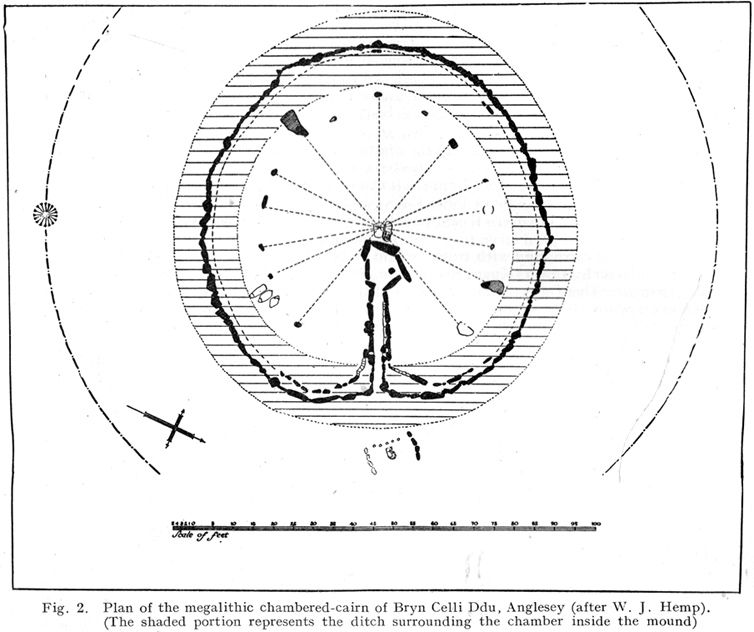

“The cairn here was circular, with a chamber of some 160ft and an original maximum height of at least 12ft. The chamber is a polygonal structure of large stones augmented…with dry-stone walling, entered on the northeast side by a long passage built in the same way. Many of the stones had been dressed and in the chamber stood a single pillar which had been artificially rounded and smoothed, but which had never actually supported the capstone.

“These features had been more or less apparent for many years. But the reparation work soon showed that this was by no means all. In the first place, it was found that the chamber had been surrounded by four circles of standing stones. The first of these, around the outside of the mound at its base, had disappeared, although early accounts and a single hole found in the course of the work of excavation, are evidence of its existence. The second and third circles were found when the entrance to the passage wall was being cleared. Here the walls of the passage were found to merge into an outer circle of large stones and an inner of smaller, set close together and elaborately packed and sunk in a ditch six feet deep and eighteen wide, enclosing the chamber in such a way that passage, chamber and circles together form a gigantic unbroken spiral, with the chamber itself as an unbroken loop in it. The fourth and innermost circle was in the area enclosed by the ditch (which is represented on the plan by the shaded portion). This consisted of a number of stones of various sizes, irregularly placed and in some cases inclined outwards. Under some of them were deposits of burnt human bones. Lines connecting these stones diametrically were found to intersect at the centre of the monument, directly behind the chamber, and here was found a slab-covered pit which contained an elaborate filling whose purpose is unexplained. Beside the cover-stone of the pit was a second larger slab of grit, lying flat, the faces of which were covered with an elaborate and continuous pattern of spirals, scrolls and zig-zags. The position of this stone is shown beside the central stone on the plan. Of it purpose it can only be said that it was probably magical…

“As if the elaborate features already described thus badly were not enough, a uniform floor of purple clay was found to cover the old natural surface within the area enclosed by the ditch, and there were on the floor, in the ditch, and in many other places extensive traces of fire in the form of burnt patches, blackening and quantities of charcoal. In addition there were outside the entrance, a line of post-holes and remains of walls suggesting the former existence of some kind of forecourt crossed by a temporary barrier. Here also were traces of fire and of elaborate ritual. It must be emphasized of course, that all these features, with the exception of the outer circle of stones and the forecourt, had been completely concealed by the mound, so that they were not visible once the monument was completed… Moreover…the entrance to the chamber had been closed with an elaborate blocking which suggested that once closed the chamber had not been intended to be re-opened.”

Although many questions emerged following the excavation, perhaps that relating to the chronology and evolution of the site (after its ritual use) was most important. The site as we see it today sits within the confines of a henge monument (which should also be given an independent entry account) and once a stone circle. And although present day field evidence is inconclusive about which came first, archaeologists like Richard Bradley, Clare o’ Kelly and others are not without opinion. Bradley (1998) told:

“O’ Kelly argued that there had been two successive monuments on the site. The earlier one was a stone circle, enclosed by the earthworks of the henge. In a later phase this was replaced by a passage grave which was built over the surviving remains of the stone circle, its outer kerb being bedded in the ditch of the older monument.”

But Bradley himself doubts this for various reasons, himself interpreting,

“the sequence at Bryn Celli Ddu is to suggest that in its first phase it consisted of a circular unrevetted mound about 15m in diameter, containing a passage grave. Around the edge of this structure was a stone circle, and beyond that there was a quarry ditch. When the monument was enlarged, not on one occasion but twice, the passage was extended as far as the earlier ditch and a significantly larger mound was bounded by kerbstones.”

Though adding himself that there is also a trouble with this idea! As with many other sites, Bryn Celli Ddu appears to have been aligned to the summer solstice. This notion was first propounded by astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer (1909) in his hugely revised work on the astronomical function of megalithic sites. It was nearly 100 years before any archaeologist got off their backside and tested Lockyer’s original proposal and found the scientist to have been way ahead of them at their own discipline. Not unsurprisingly, archaeologist Mike Pitts (2006) was a bit slow in his gimmicky headline in British Archaeology, where he deemed Steve Burrow’s personal observation as “sensational.” Oh how common this theme seems to be in archaeology. Twenty years previously Miranda Green (1991) posited that the chamber alignment from Bryn Celli Ddu aligned towards “May Day sunrise” — which doesn’t seem to work. And on a similar astronomical note, archaeologist Julian Thomas (1991) thought that five post-holes found some five yards beyond the entrance were somewhat reminiscent of the “A” holes at Stonehenge and related to some lunar alignments, thinking that:

“It seems likely that (they) record a series of observations upon the rising of some heavenly body in order to ascertain its standstill position.”

A point that Clive Ruggles (1999) explored with a little scepticism, pointing out:

“The only possibility is the northern minor limit of the moon, and while the adjacent posts are ranged on the correct side to record the position, say, of the midwinter full moonrise in years before and after the minor standstill, many other interpretations of these posts are doubtless possible.”

There’s been lots written about this place and lots more could be added with various archaeologists showing their relative opinions about the place. But perhaps more worthwhile is a visit to the place, later on, when the tourists have fallen back under a starlit sky…

References:

- Anonymous, “Cromlech at Bryn Celli Ddu, Anglesey,” in Archaeologia Cambrensis, volume 2, 1847.

- Barber, Chris & Williams, John G., The Ancient Stones of Wales, Blorenge: Abergavenny 1989.

- Bradley, Richard, “Stone Circles and Passage Graves – A Contested Relationship,” in Prehistoric Ritual and Religion, edited by Alex Gibson & Derek Simpson (Sutton: Stroud 1998).

- Green, Miranda, The Sun Gods of Ancient Europe, Batsford: London 1991.

- Grimes, W.F., “Prehistoric Archaeology in Wales since 1925,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, 7:1, 1932.

- Hemp, W.J., “The Chambered Tomb of Bryn Celli Ddu, Anglesey,” in Archaeologia, volume 80, 1930.

- Lockyer, Norman, Stonehenge and other British Stone Monuments Astronomically Considered, MacMillan: London 1909.

- Lynch, Frances, Prehistoric Anglesey, Anglesey Antiquarian Society 1991.

- o’ Kelly, Clare, “Bryn Celli Ddu: A Reinterpretation,” in Archaeologia Cambrensis, volume 118, 1969.

- Ruggles, Clive, Astronomy in Prehistoric Britain and Ireland, Yale University Press 1999.

- Thomas, Julian, Rethinking the Neolithic, Cambridge University Press 1991.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian