Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 82274 16125

Also Known as:

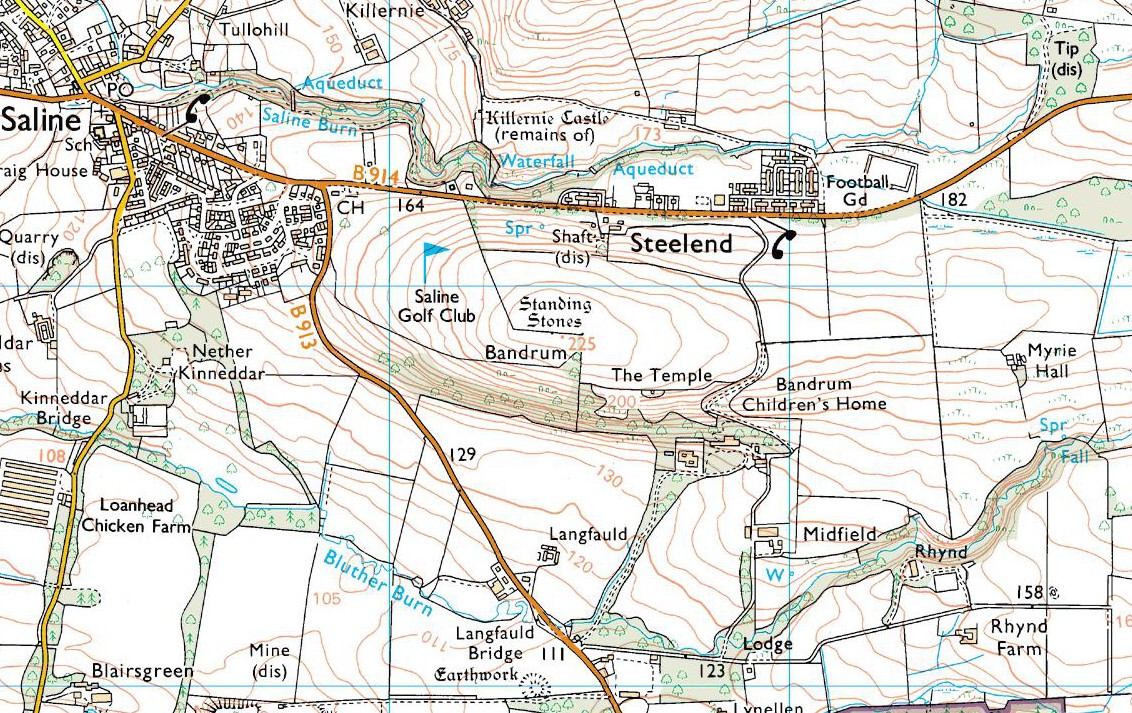

Along the A822 road between Crieff and Muthill, take the small western country lane just as you’re coming out of Muthill. Nearly 2 miles on, take the turn to the right, and then 100 yards or so from there turn sharp left. Keep along this gorgeous country lane for about a mile till you reach the third track on your left and park up. Walk down the track and you’ll see the standingh stone in the field on your right. Go all the way to the bottom where the farm is and go through the gate into the field.

Archaeology & History

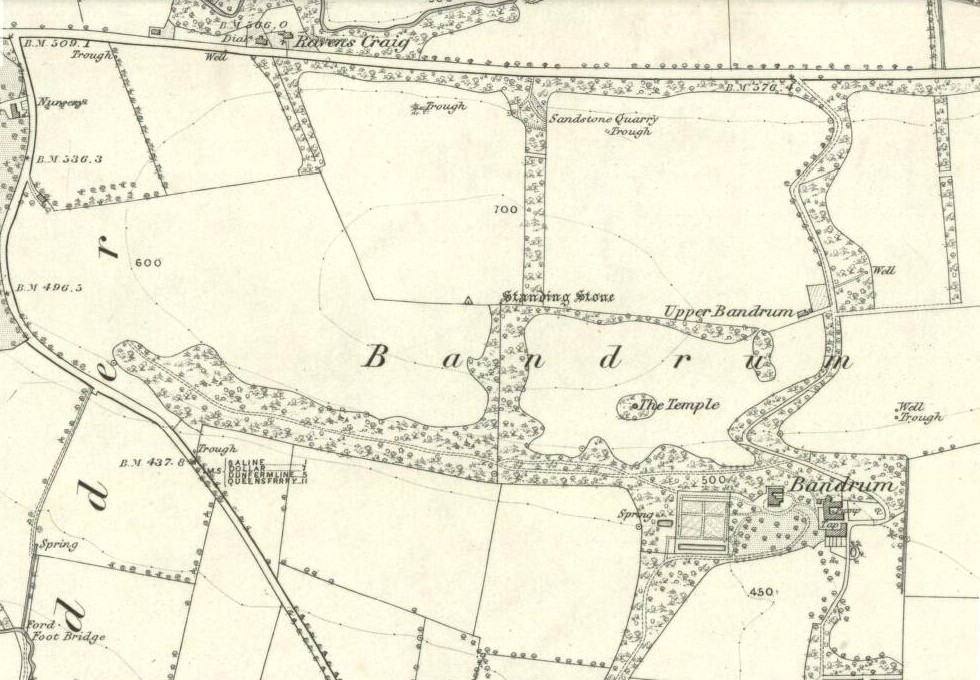

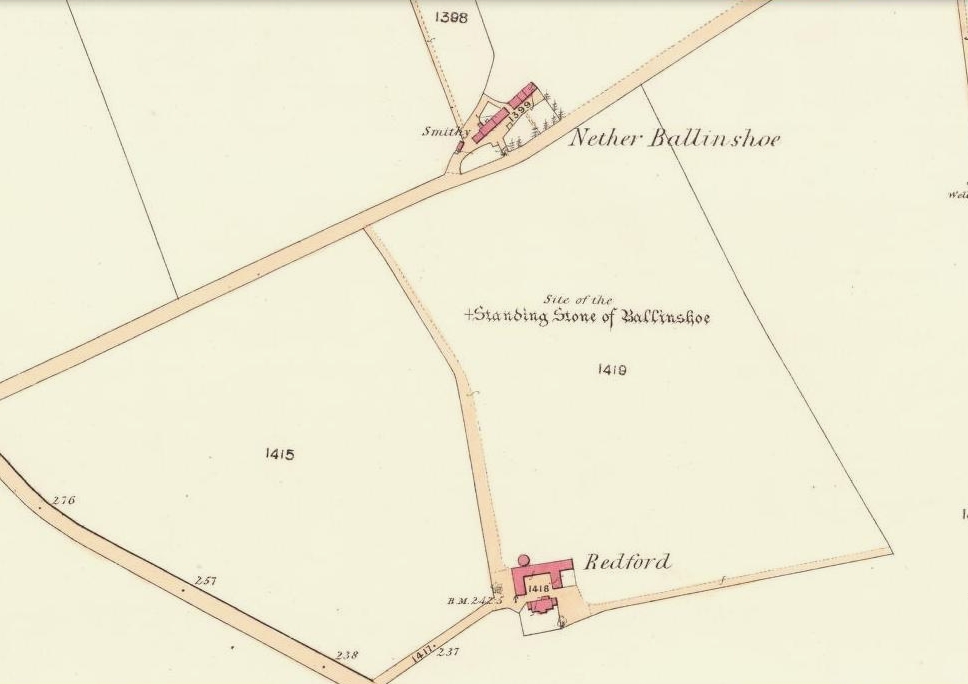

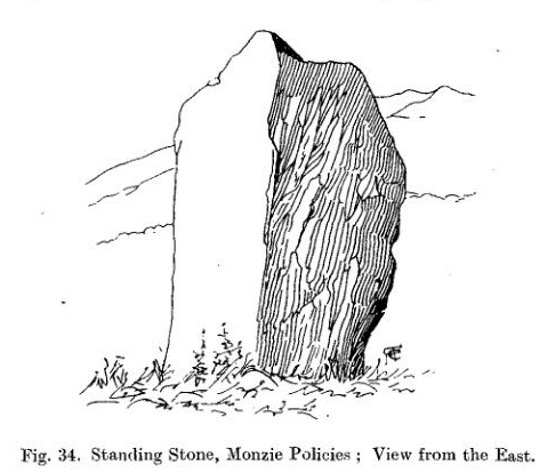

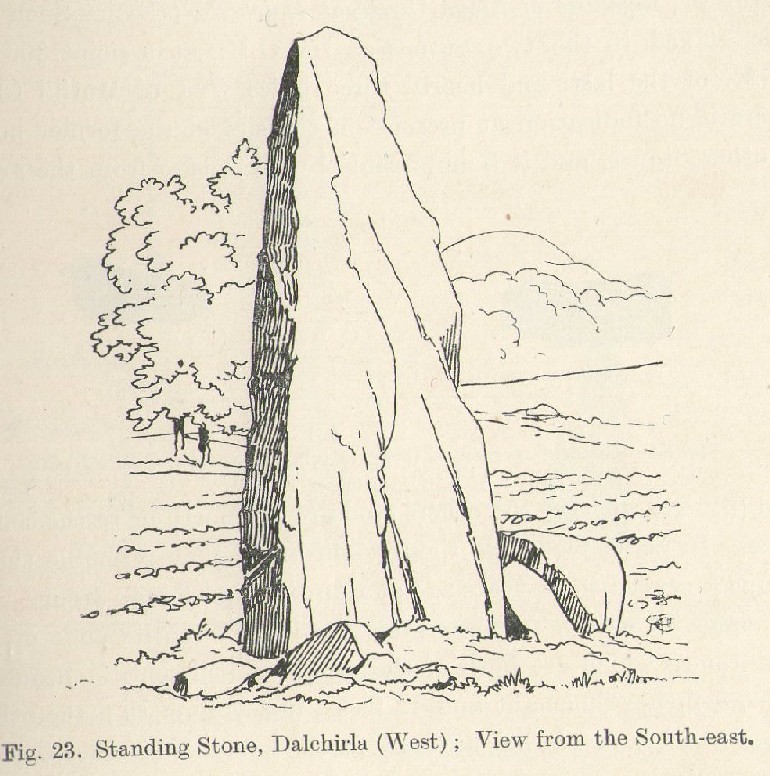

Less than 2 miles southeast of the megalithic titan of Dunruchan A, we find a slightly smaller monolith positioned on lower ground and humbled by a more manicured landscape close to the farmhouse. But it’s still a big fella, albeit hemmed in by a mass of field clearance rocks piled up and around the base (two of which have odd carvings on them). The stone is about ten-feet tell, being very slim on its north-south side and much wider on its east-west face. For some reason I got the impression that the stone wasn’t standing in its original position; though in searching through my megalith library for further information on the site, l found that very little has been written about it. The earliest literary evidence comes, as usual, from Fred Coles (1911), who simply told us:

“In a field south of Machany Water and NE of Dalchirla farm-steading 260 yards, there stands this tall and striking monolith… In essential features this stone much resembles most of the great schistose blocks which characterize the main portion of the Strathearn area; but it tapers upwards to a very thin and narrow summit that rather distinguishes it from its fellows. It stands 9 feet 4 inches above ground, and girths at the base 7 feet 11 inches. It is set with its longer axis due north and south. Around its base there are several large masses of stone—not earthfast—amid a conglomeration of smaller pieces evidently cleared off the field.”

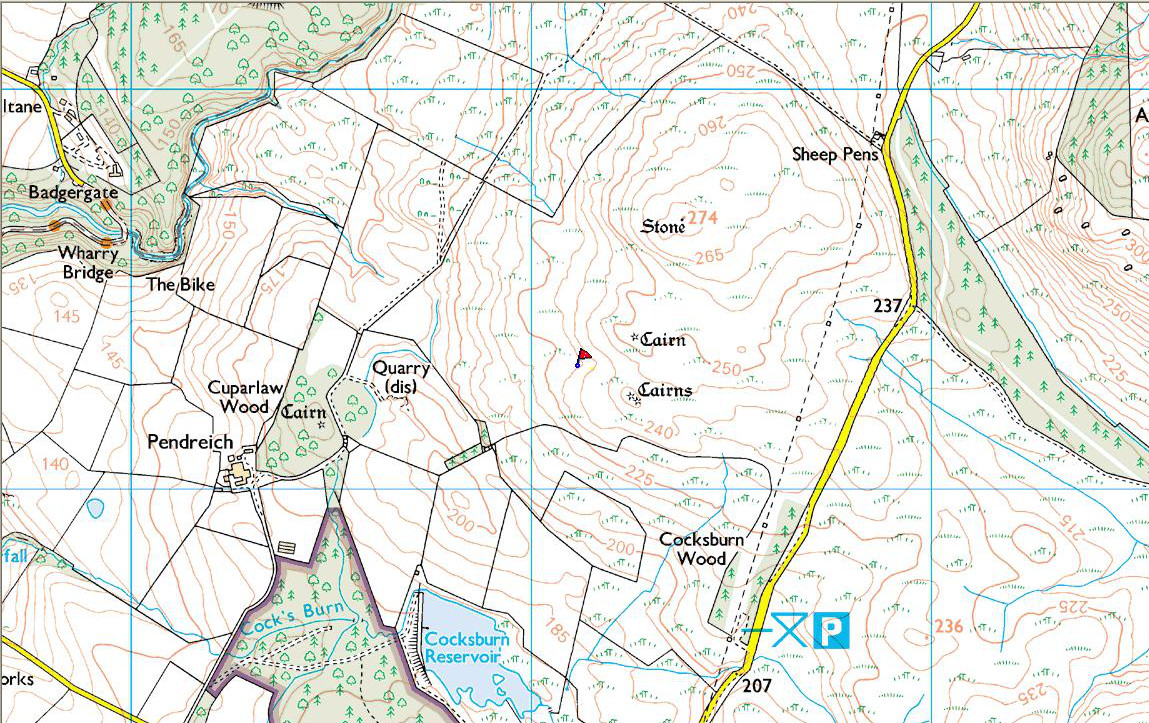

The prehistoric cairn of Torlum to the north may have had some significance to the setting of the stone, but without excavation and details of its original site, we’re just grasping at straws when it comes to evaluating any potential geomancy or landscape relationships—with the megalithic stone row in the next field perhaps being an exception!

The moorlands above here, stretching for many a mile, is apparently lacking in any prehistoric remains if you listen to the official records. But with the Dunruchan megalithic complex only two miles away and the once-giant tomb of Cairnwochel over the southeastern horizon, we know that cannot be possible… Watch this space!

References:

- Coles, Fred, “Report on Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire, Principally Strathearn” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 45, 1911.

- Finlayson, Andrew, The Stones of Strathearn, One Tree Island: Comrie 2010.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian