Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 14442 44281

Getting Here

Your best starting point is from the Great Skirtful of Stones giant cairn. From here follow the fencing that runs down the slope to your left (south-east) for roughly 160 yards (148m) – past the Great Skirtful Ring – until you reach the gate. Go through it and keep walking down the same fence-line for 300 yards then walk south onto the moorland proper (there are no paths here). You’ll pass over several undulations in the heather (some of these are the edges of ancient trackways) and 55-60 yards south from the fencing you’ll walk over and into this overgrown prehistoric ring. It’s very difficult to see when the vegetation is deep, so persevere!

Archaeology & History

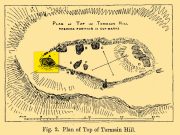

This is an interesting site. Marked on the 1851 Ordnance Survey map as a “barrow” (right), it is shown with trackways on either side of it to the north and south, and with an opening or entrance on its northwestern side. Yet since that date, very little archaeological attention has been given to it and the site remains unexcavated, despite its location being repeated on all subsequent maps since then. The designation of the site as a barrow or burial site, without being excavated, was educated guesswork at the time as the place seems to be what we today define as a ring cairn. And whilst this seems likely, there are some oddities here.

Measuring roughly 25 yards (SE – NW) by 21 yards (NE – SW), this overgrown oval ‘ring’ is a similar architectural structure to the more famous Roms Law circle more than half-a-mile northwest of here—but bigger! And, unlilke Roms Law, this overgrown circle seems to have been untouched for many centuries. The oval surrounding ‘ring’ itself is composed of thousands of small packing stones between, seemingly, a number of much larger upright stones, reaching a maximum height of more than three feet high at the northernmost edge. The ‘ring’ ostensibly looks like a wide surrounding wall which measures two yards across all round the structure.

Internally, there seems little evidence of a burial — although our recent visits here, as the photos indicate, took place when the moorland vegetation was deep and covered almost the entire site. The outline of the site is obviously visible, even in deep heather, but the smaller details remain hidden. But in addition to the main ring, another very distinct ingredient here is the existence of an extended length of man-made parallel walling, probably a trackway, that runs into the circle from the southeast all the way through the circle and out the other side and then continuing northwest heading roughly towards the Great Skirtful giant cairn on the horizon 500 yards to the northwest.

Due to the landscape being so overgrown, it’s difficult to ascertain where this ‘trackway’ begins and ends. Added to this, we find that there are additional ‘trackways’ that run roughly parallel to the one that runs through the circle—and these ‘trackways’ are very old indeed, some of them likely have their origins way back in prehistory. The one that runs through the middle of this ring cairn may be a ceremonial pathway along which, perhaps, our ancestors carried their dead. If we follow it out from here and keep walking along the track 300 yards to the southeast, we eventually run right to the edge of the Craven Hall (3) circle. Parallel to this is another ancient trackway that runs northwest to the edge of the Roms Law circle. It seems very much as if we have ceremonial trackways linking sites to each other: ancestral pathways, so to speak.

Have a gander at this when you’re next in the area. There are many other sites nearby that are off the archaeological radar. In recent years, a number of northern antiquarians wandering over this landscape are finding more and more ancient remains: walling, circles, cairns, trackways. It’s a superb arena—but sadly, most of it is hidden beneath deep moorland vegetation.

References:

- Faull, M.L. & Moorhouse, S.A. (eds.), West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Guide to AD 1500 – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian