Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference – NN 9610 0018

Getting Here

The marshland of the Butter Well

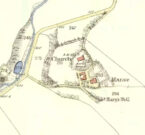

Take the long uphill road to Castle Campbell and park up at the top. From here, bear to your right and walk up the footpath onto the hills. A few hundred yards along you’ll reach a gate and you have the choice of continuing along the path, or dropping down into the small glen and up the other side, towards the ruins of an old settlement called Craiginnin, whose walls you can see from here. Head there, keeping to the path that leads you to it, going through the first couple of gates and out the other side. Just above the burn, some very overgrown walling is evident (possibly Iron Age in nature), where excessive Juncus reeds are growing. Amidst this is a boggy pool. Unless the boggy-land across the burn is the place in question, this is probably the spot!

Archaeology & History

The boggy waters of the well

There’s very little to see here today other than a murky boggy pool, indicating it hasn’t been used for a long time; although when we visited the place there were several animal tracks into the edge of the pool, indicating that they still drink here. This implies it has/had some medicinal virtues, but even I wasn’t going to try drinking this! If there was ever a stone trough here, it too has gone (probably nabbed by a farmer in bygone years) and there seems to be no archaeocentric reference to the place. The well was described in place-name and folklore accounts, where its waters were used by the people living at this settlement to clean and prepare the butter made by the farmer.

Folklore

The hills, glens and burns of the Ochil range were well-known haunts of fairy folk—and Craiginnan was no exception. In an early article in the Scottish Journal of Topography, a pseudonymous “J.C.” of “13 Dalrymple Place” (who was it?) told of several dying traditions and, amidst it all, the story behind the Butter Well above Castle Campbell:

“The meadow of Craiginnan, in the vicinity of these hills, was (and still is) famous for the quantities of hay it yearly produces. Nearly seventy years ago, David Wright rented the farm of Craiginnan. His servants on cutting the grass of the meadow, were in the custom of leaving it to the management of the fairies. These aerial beings came from Blackford, Gleneagles, Buckieburn, etc., and assembling on the summit of the Saddlehill descended to their work among the hay. From morning till evening they toiled assiduously. After spreading it out before the sun, they put it into coils, then into ricks, when it was conveyed into the adjacent farm-yard, where they built it into stacks. This kindness of the fairies David Wright never forgot to repay, for, when the sheep-shearing came round, he always gave them a few of the best fleeces of his flock. He flourished wonderfully, but finding his health daily declining, and seeing death would soon overtake him, he imparted to his eldest son the secret of his success and told him ever to be in friendship with the “gude neebors.”

“The old man died and was succeeded by his son, who was at once hard, grasping and inhospitable. The kind advices and injunctions given him by his father were either forgotten or unattended to. Hay-making came round, but young Wright, instead of allowing the “green-goons” to perform what they had so long done (thinking thereby to save a few fleeces), ordered his servants to the work. Things went on very pleasantly the first day, but on going next morning to resume their labour, what was their surprise to find the hay scattered in every direction. Morning after morning this was continued, until the hay was unfit for use. In revenge for this, he destroyed the whole of their rings, ploughed up their green knolls, and committed a thousand other offences. He had soon reason, however, to repent of these ongoings.

“One day the dairymaid having completed the operation of churning, carried the butter, as was her wont, to the butter well on the east side of the house, to undergo the process of washing, preparatory to its being sent away to the market. No sooner had she thrown it into the well, than a small hand was laid upon it, and in a second the bright golden treasure disappeared beneath the crystal waters! The servant tried to snatch it; but alas! it was lost—irrecoverably lost forever! and as she left the place a voice said:

“Your butter’s away’

To feat our band

In the fairy ha’.”

“The horses, cows and sheep sickened and died; and to complete all, Wright, on returning from a Glendevon market, night overtook him in the wild pass of Glenqueich. He wandered here and there, and at last sunk into a “well-e’e”, in which he perished. After his death the farmhouse went gradually to demolition and its bare walls are now only to be seen.”

Butter Well site, looking west

The place-name ‘Craiginnan’ is thought to derive from the somewhat banal “crags by the anvil-shaped land”, which is grasping at some desperate straws if you ask me! But it’s also been suggested by Angus Watson (1995) to possibly derive from the “Gaelic Creag Ingheann, maiden crag”, which would acquaint it with the nearby Maiden’s Well and Maiden’s Castle a mile northeast of here—both of which are possessed of their own fairy-lore. Makes a lot more sense too!

References:

- “J.C.”, “Rhymes and Superstitions of Clackmannanshire,” in Scottish Journal of Topography, Antiquities & Traditions, volume 2, Jul 1, 1848.

- Simpkins, John Ewart, County Folklore – volume VII: Examples of Printed Folk-Lore Concerning Fife, with some Notes on Clackmannan and Kinross-Shires, Folk-Lore Society: London 1914. p.312

- Watson, Angus, The Ochils: Placenames, History, Tradition, PKDC: Perth 1995.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian