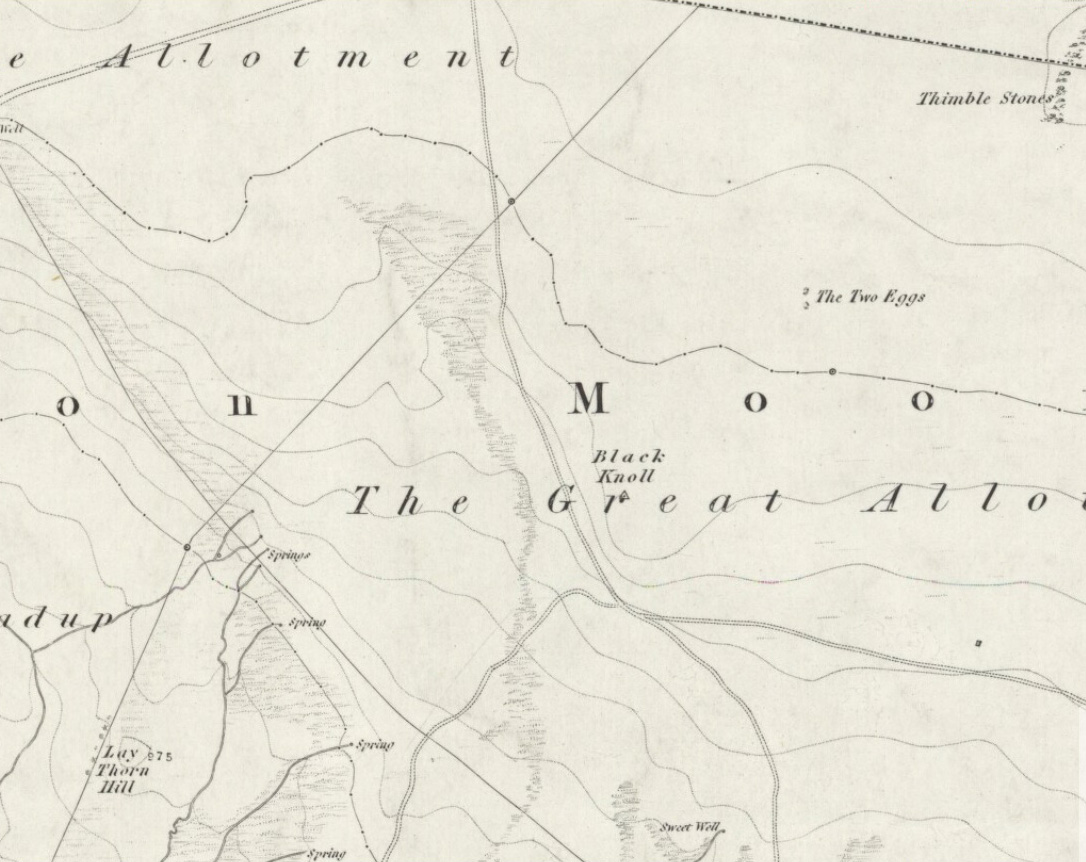

Cairns: OS Grid Reference – SE 170 507– NEW DISCOVERY

From the large parking spot by the roadside along Askwith Moor Road, walk up (north) 250 yards until you reach the gate with the path leading onto Askwith Moor. Follow this along, past the triangulation pillar until you reach the Warden’s Hut near the top of the ridge and overlooking the moors ahead. Naathen — look due south onto the moor and walk straight down the slope till the land levels out. If you’re lucky and the heather aint fully grown, you’ll see a cluster of stones about 500 yards away. That’s where you’re heading. If you end up reaching the Woman Stone carving, you’ve walked 100 yards past where you should be!

Archaeology & History

Discovered on the afternoon of May 13, 2010, amidst another exploratory ramble in the company of Dave Hazell. We were out looking for the Woman Stone carving and a few others on Askwith Moor, and hoping we might be lucky and come across another carving or two in our meanderings. We did find a previously unrecorded cup-marked stone (I’ll add that a bit later) — and a decent one at that! — but a new cairn-field was one helluva surprise. And in very good nick!

There are several cairns sitting just above the brow of the hill, looking into the western moors. Most of these are typical-looking single cairns, akin to those found on the moors above Ilkley, Bingley and Earby, being about 3 yards across and a couple of feet high amidst the peat and heather covering. But two of them here are notably different in structure and size (and please forgive my lengthy description of them here).

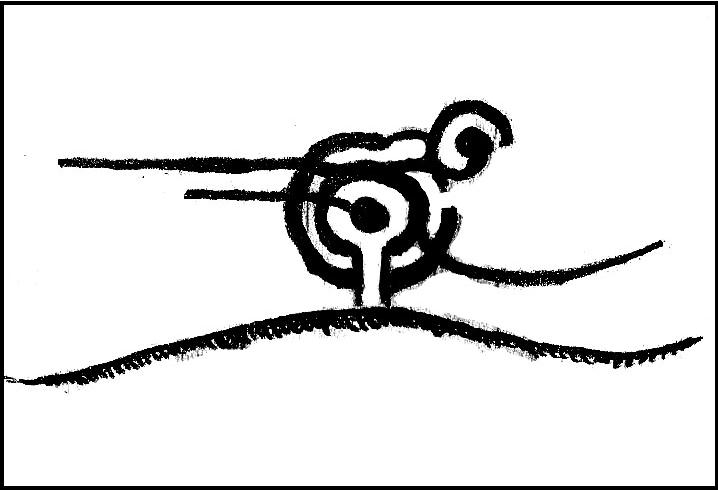

We found these tombs after noticing a large section of deep heather had been burnt back, and a large mass of rocks were made visible as a result. Past ventures onto these moors when seeking for cup-and-ring carvings hadn’t highlighted this cluster, so we thought it might be a good idea to check them out! As I approached them from the south from the Woman Stone carving (where we’d sat for a drink and some food, admiring the moors and being shouted at by a large gathering of geese who did not want us here), it became obvious, the closer I got, that something decidedly man-made was in evidence here.

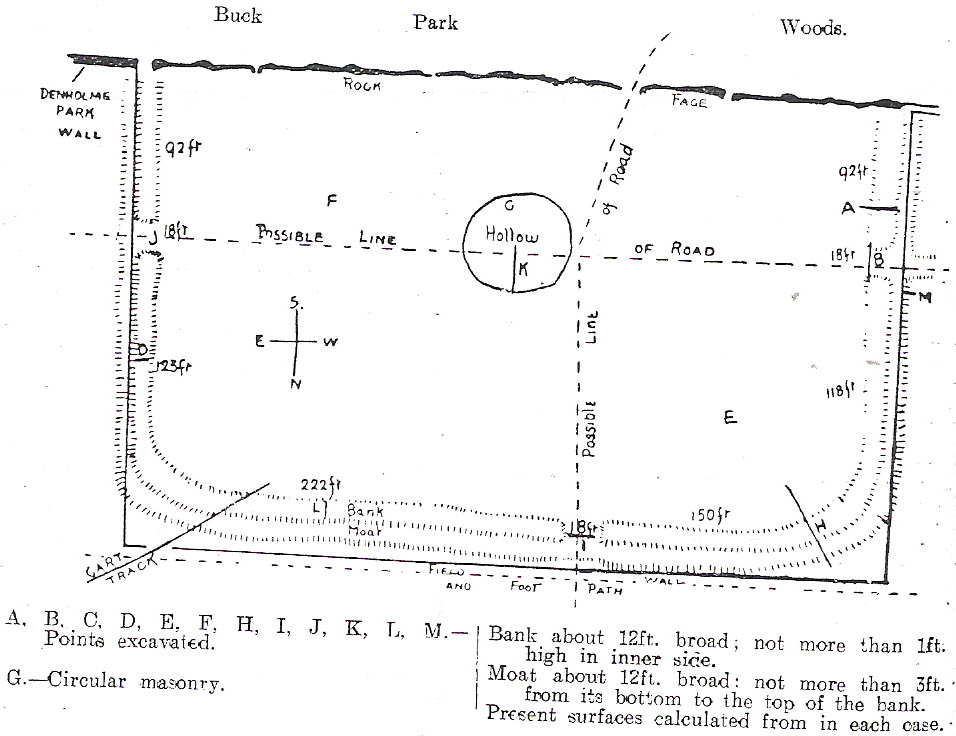

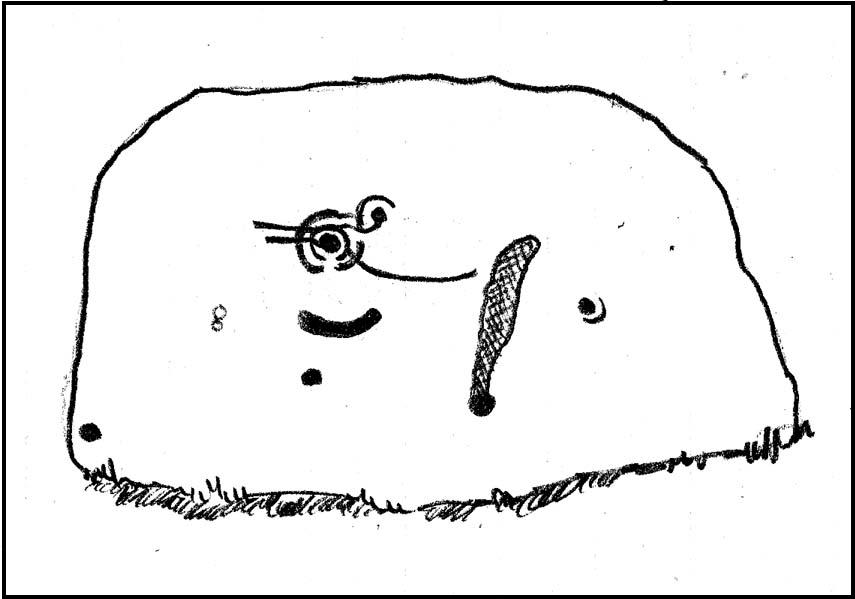

Walking roughly northwards out of the heather and onto the burnt ground, a cairn-like feature (hereafter known as “Cairn A”) was right in front of me; though this seemed to have a ring of small stones — some earthfast, others placed there by people — surrounding the stone heap. And, as I walked around the edge of this large-ish cairn (about 9 yards in diameter and 2-3 feet tall), it was obvious that a couple of these outlying stones were stuck there by humans in bygone millenia. The most notable feature was the outlying northernmost upright: a small standing stone, coloured white and distinctly brighter than the common millstone grit rock from which this monument is primarily comprised. As I walked round it — adrenaline running and effing expletives emerging the more I saw — it became obvious that this outlying northern stone had long lines of thick quartz (or some crystalline vein) running across it, making it shine very brightly in the sunlight. Other brighter stones were around the edge of the cairn. It seemed obvious that this shining stone was of some importance to the folks who stuck it here. And this was confirmed when I ambled into another prehistoric tomb about 50 yards north, at “Cairn B.”

Cairn B was 11 yards in diameter, north-south, and 10 yards east-west. At its tallest height of only 2-3 feet, it was larger than cairn A. This reasonably well-preserved tomb had a very distinct outlying “wall” running around the edges of the stone heap, along the edge of the hillside and around onto the flat moorland. Here we found there were many more stones piled up in the centre of the tomb, but again, on its northern edge, was the tallest of the surrounding upright stones, white in colour (with perhaps a very worn cup-marking on top – but this is debatable…), erected here for some obviously important reason which remains, as yet, unknown to us. Although looking through the centre of the cairn and onto the white upright stone, aligning northwest on the distant skyline behind it, just peeping through a dip, seems to be the great rocky outcrop of Simon’s Seat and its companion the Lord’s Seat: very important ritual sites in pre-christian days in this part of the world. Near the centre of this cairn was another distinctly coloured rock, as you can see in the photo, almost yellow! Intriguing…

Within a hundred yards or so scattered on the same moorland plain we found other tombs: Cairns C, D, E, F, G and H — but cairns A and B were distinctly the most impressive. An outlying single cairn, C, typical of those found on Ilkley Moor, Bingley Moor, Bleara Moor, etc, was just five yards southwest of Cairn A, with a possible single cup-marked stone laying on the ground by its side.

Just to make sure that what we’d come across up here hadn’t already been catalogued, I contacted Gail Falkingham, Historic Environment team leader and North Yorkshire archaeological consultant, asking if they knew owt about these tombs. Gail helpfully passed on information relating to a couple of “clearance cairns” (as they’re called) — monument numbers MNY22161 and MNY 22162 — which are scattered at the bottom of the slope below here. We’d come across these on the same day and recognised them as 16th-19th century remains. The cairnfield on top of the slope is of a completely different character and from a much earlier historical period.

We know that human beings have been on these moors since mesolithic times from the excess of flints, blades and scrapers found here. Very near to these newly-discovered tombs, Mr Cowling (1946) told that:

“On the western slope of the highest part of Askwith Moor is a very interesting flaking site. For some time flints have been found in this area, but denudation revealed the working place about August, 1935. There were found some twenty finished tools of widely different varieties of flint. A large scraper of red flint is beautifully worked and has a fine glaze, as has a steep-edged side-blow scraper of brown flint. A small round scraper of dull grey flint has the appearance of newly-worked flint, and has been protected by being embedded in the peat…One blade of grey flint has been worked along both edges to for an oblong tool… The flint-worker on this site appears to have combed the neighbourhood to supplement the small supply of good flint.”

All around here we found extensive remains of other prehistoric remains: hut circles, walling, cup-and-ring stones, more cairns, even a probable prehistoric trackway. More recently on another Northern Antiquarian outing, we discovered another previously unrecognised cairnfield on Blubberhouse Moor, two miles northwest of here.

References:

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way: A Prehistory of Mid-Wharfedale, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Jack, Jim, “Ancient Burial Ground and Bronze Age Finds on Moor,” in Wharfedale Observer, Thursday, May 27, 2010.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian