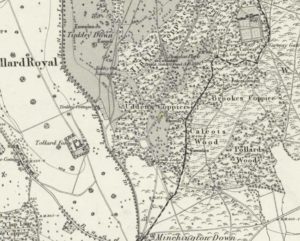

Cairnfield: OS Grid Reference – NC 7279 6232

From Bettyhill, go out of the village along the A836 Thurso road for just over a mile. You go uphill for a few hundred yards and just as the road levels-out, there’s the small Farr Road on your left and the cattle-grid in front of you. Just before here is a small cottage on your left. In the scrubland on the sloping hillside just below the cottage, a number of small mounds and undulations can be seen. That’s it!

Archaeology & History

Although this place was highlighted on the first OS-map of the area in 1878, I can only find one modern reference describing this somewhat anomalous cluster of sites. It’s anomalous, inasmuch as it doesn’t have the general hallmark of being a standard cairnfield or cluster of tumuli. For one, it’s on a slightly steep slope; and another is that amidst what seems to be cairns there are other, more structured remains. As I wandered back and forth here with Aisha, I kept shaking my head as it seemed somewhat of a puzzling site. As it turns out, thankfully, I wasn’t the only one who thought this…

In R.J. Mercer’s (1981) huge work on the prehistory of the region, he described the site as a whole as a field system comprising “enclosures, structures, cairns and field walls” and is part of a continual archaeological landscape that exists immediately east, of which the impressive Fiscary cairns are attached. In all, this ‘cairnfield’ or field system is made up of at least 23 small man-made structures, with each one surviving “to a height of c.0.5m and are associated with 11 cairns from 2-6m is diameter.”

In truth, this site is probably of little interest visually unless you’re a hardcore archaeologist or explorer.

References:

- Mercer, R.J., Archaeological Field Survey in Northern Scotland – volume 2: 1980-1981, University of Edinburgh 1981.

Acknowledgments: To the awesome Aisha Domleo, for her images, bounce, spirit and madness – as well as getting me up here to see this cluster of sites.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian