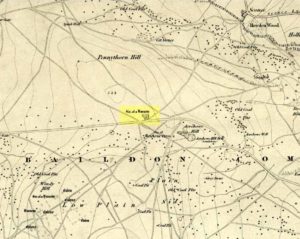

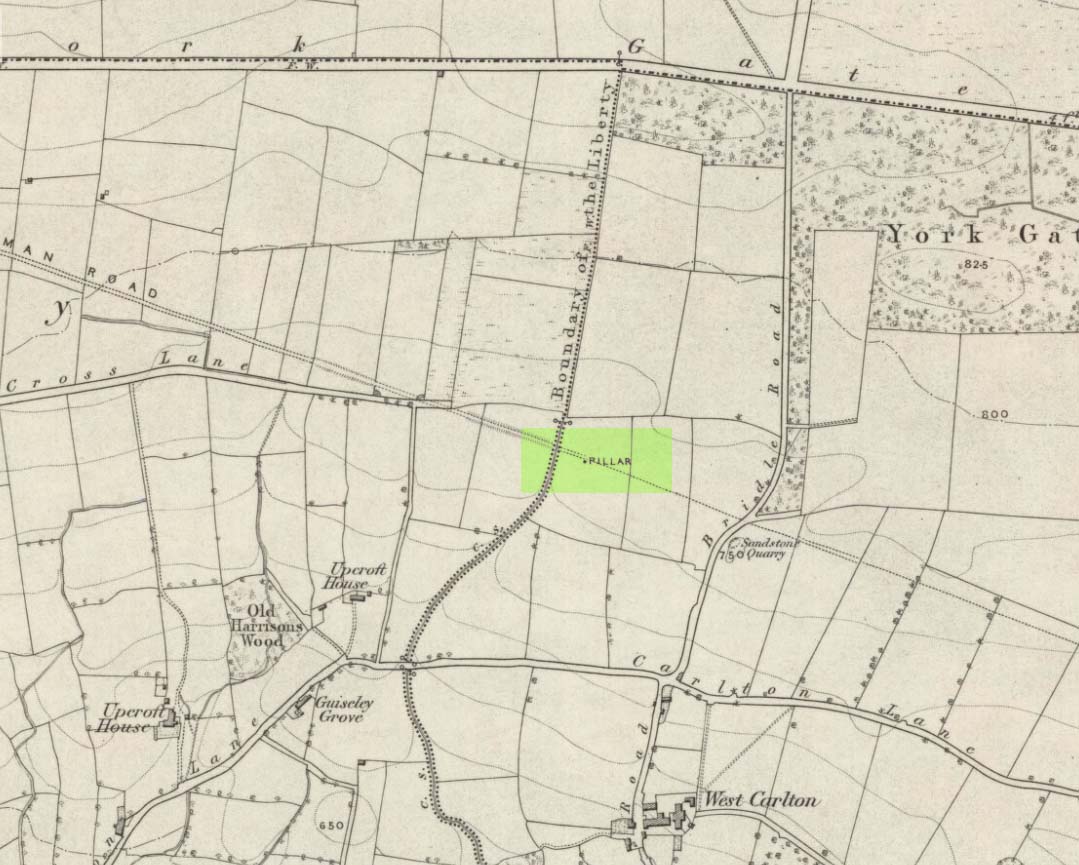

Standing Stone/s: OS Grid Reference – SE 20675 43469

Also Known as:

- Boon Stones

- Boul Stones

- Bull Stone of Otley Chevin

Getting Here

Worth checking this if you aint seen it before! Head up to the back (south-side) of Otley Chevin (where the cup-and-ring Knotties Stone lies sleeping), following the road there and park up near/at the Royalty pub. Take the footpath behind the pub which crosses the fields and once into the second field, head diagonally down to the far-left corner. From here, look over the wall — you can’t really miss it!

Archaeology & History

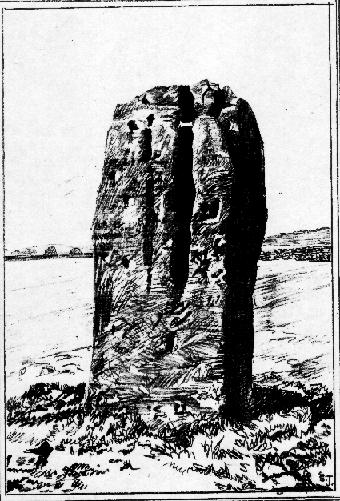

An intriguing site for various reasons. All we have left to see of any value nowadays is this nigh-on 6-foot tall thick monolith, standing alone in the field halfway between West Carlton and Otley Chevin. Completely missed in local archaeological surveys, the place was mentioned briefly by Slater (1880); though it appears to have been first described in detail by Eric Cowling (1946), who suspected the stone may have Roman origins (though didn’t seem too convinced!), saying that:

“near the ground the section is almost oblong, with sides three-feet six-inches by one-foot ten-inches; two feet from top, the section is almost circular.”

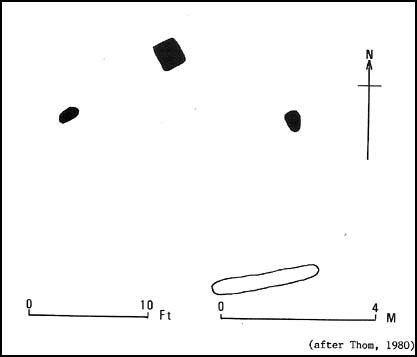

The fact that the stone stands very close to the line of an all-but forgotten Roman road that runs right past it added weight to this thought (the road runs towards a Roman settlement a mile east of here near Yeadon). But this standing stone is unlikely to be Roman. More recent evidence seems to indicate a relationship with a now-lost giant cairn about 100 yards to the south. The only remains we have of this place are scatterings of many small loose stones nearby. And it seems a very distinct possibility that the extra standing stones that were once hereby, stood in a line.

The very first reference I’ve found about this site also indicates that there was more than one stone here in the past! In 1720 this site was known as the ‘Boon Stones’; and the plural was still being used by the time the 1840 Tithe Awards called them the ‘Boul Stones.’ Initially it was thought that both words were plural for “bulls” — as A.H. Smith (1962) propounds in his otherwise superb survey — but this is questionable. (see Folklore)

Folklore

A piece of folklore that seems to have been described first by Philemon Slater (1880) relates to the pastime of bull-baiting here, that is –

“fastening bulls to it when they were baited by dogs, a custom…still known to the Carlton farmers” (North Yorkshire).

Cowling (1946) told that he heard the stone was said to be lucky as well as being a source of fertility. This ‘fertility’ motif may relate to the meaning of the stone’s early name, the Boon Stones. Both boon and boul are all-but obsolete northern dialect words. ‘Boul’ is interesting in its association with a prominent folklore character, as it was used as a contemptuous term “for an old man.” Now whether we can relate this boul to the notion of the ‘Old Man’ in British folklore, i.e., the devil, or satan — as with the lost standing stone of The Old Man of Snowden, north of Otley — is difficult to say.

More interestingly perhaps is the word ‘boon’, as it is an old dialect word for “a band of reapers, shearers, or turf-cutters.” This band of reapers ordinarily consisted of five or six people and would collect the harvest at old harvest times. And as the early description talks of Boon Stones, this plurality would make sense. One curious, though not unsurprising folklore relic relating to these boons was described at another megalithic site (now gone) by John Brand (1908), where in the parish of Mousewald in Dumfries,

“The inhabitants can now laugh at the superstition and credulity of their ancestors, who, it is said, could swallow down the absurd nonsense of ‘a boon of shearers,’ i.e., reapers being turned into large grey stones on account of their kemping, i.e., striving.”

Standing stones with the folklore of them being men or women turned to stone is common all over the world. If we accept the dialect word ‘boon’ as the first name of this old stone, there may once have been some harvest-time events occurred here long ago (and this is quite likely). Equally however, we must also take on the possibility that this Bull Stone has always been a loner and that its name came from the now obsolete Yorkshire word, a bull-steann, meaning a stone used for sharpening tools, or a whetstone.

Take your pick!

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Brand, John, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain – volume 2, George Bell: London 1908.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Jackson, Sidney, ‘The Bull Stone,’ in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 2:5, 1956.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – 2 volumes, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 7, Cambridge University Press 1962.

- Slater, Philemon, The History of the Ancient Parish of Guiseley, William Walker: Otley 1880.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian