Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 4832 6173

Getting Here

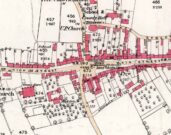

Ghaist Stane on 1865 OS-map

Whichever route you take to reach this lovely hamlet, hiding away in deep greenery, when you get to the one and only road junction, where it goes downhill (towards the old church), look just above you just below the first tree. All but covered in vegetation, the ruined stone lays down there. Climb up and see!

Archaeology & History

Tis up on the verge here

An exploration of this site was prompted when fellow antiquarian, Paul Hornby, came across the curious place-name of ‘Ghaist Stane’ when he was looking over some old Ordnance Survey maps of the region. So we met up and took a venture over there! Last highlighted on the 1865 map (when the old village was known as Fearn, not the modern spelling), even the Canmore lads had missed this one. But it’s not easy to find….

After meandering back and forth by the village roadside, on the tops of the walls, into the field above, Paul eventually said, “Is that it?!” just above the roadside, almost buried in vegetation below the roots of a tree. So I clambered back up and brushed some of the vegetation away – and there it was – in just the place that the old OS-map showed it to be (give or take a few yards).

The remains of the stone measure roughly 3 feet by 3 feet; with the present upper portion of the stone being of a lighter colour than the lower portion, indicating that this section of the stone was the portion that was underground when it was standing upright. Its history is fragmentary, but we know that it was almost completely destroyed in the middle of the 19th century. Notes from the Object Name Book of the region in 1861 told,

“The “Ghaist Stane”…formerly well known, is becoming little known from the stone having been recently blasted in making the Dike it now forms a part of, but it may be observed in the wall as a huge stone much larger than those beside it in the Dike. It does not project now from the side of the Road.”

Now the stone is almost entirely forgotten and lays covered, ignored, even by local people. It could do with being resurrected and its heritage preserved before it disappears forever.

Folklore

The uncovered Ghaist Stane

The word “ghaist” is a regional dialect word meaning “a ghost or goblin”, inferring that the site was haunted. And, considering the inherent animistic cultural psychology of the people here in earlier centuries, we must also consider the distinct possibility that the stone itself was the abode of a resident spirit, perhaps an ancestral one of a local chief, or queen, or elder of some sort.

In James Guthrie’s (1875) analysis of the folklore of Fern township, he told of the peculiarly odd violent brownies of the district and thought that they and the spirit of the Ghaist Stane were one and the same.

“In addition to the leading characteristics of Brownies in general the more prominent of these being, that they forded the rivers when their waters were at their highest, and that the sage femme always landed safely at the door of the sick wife—the brownies of Ferne are connected with scenes of cruelty and bloodshed. This peculiarity would seem to indicate that the brownie and the ghaist of Feme, were one and the same. The Ghaist Stane is in the vicinity of the church. To this piece of isolated rock, it is said this disturber of the peace was often chained as a fitting punishment for his misdeeds, but tradition is silent as to the brownie being similarly dealt with, which strengthens the supposition that they were, in this quarter at least, generally regarded as one being.”

The spirit of the Ghaist Stane roamed far and wide in the district it seemed, and a long rhyme telling a tale of the ghaist was once well-known in the area which, thankfully, Mr Guthrie gave us in full:

THE GHAIST O’ FERNE-DEN

There liv’d a farmer in the North,

(I canna tell you when),

But just he had a famous farm

Nae far frae Feme-den.

I doubtna, sirs, ye a’ hae heard,

Baith women folks an’ men,

About a muckle, fearfu’ ghaist —

The ghaist o’ Ferne-den!

The muckle ghaist, the fearfu’ ghaist,

The ghaist o’ Ferne-den;

He wad hae wrought as muckle wark

As four-au’-twenty men!

Gin there was ony strae to thrash,

Or ony byres to clean,

He never thocht it muckle fash

0′ workin’ late at e’en!

Although the nicht was ne’er sae dark,

He scuddit through the glen,

An’ ran an errand in a crack —

The ghaist o’ Ferne-den!

Ane nicht the mistress o’the house

Fell sick an’ like to dee,—

“O! for a oanny wily wife!”

Wi’ micht an’ main, cried she!

The nicht was dark, an’ no a spark

Wad venture through the glen,

For fear that they micht meet the ghaist —

The ghaist o’ Ferne-den!

But ghaistie stood ahint the door,

An’ hearin’ a’ the strife,

He saw though they had men a score,

They soon wad tyne the wife!

Aff to the stable then he goes,

An’ saddles the auld mare,

An’ through the splash an’ slash he ran

As fast as ony hare!

He chappit at the Mammy’s door—

Says he — “mak’ haste an’ rise;

Put on your claise an’ come wi’ me,

An’ take ye nae surprise!”

“Where am I gaun?” quo’ the wife,

“Nae far, but through the glen —

Ye’re wantit to a farmer’s wife,

No far frae Ferne-den!”

He’s taen the Mammy by the hand

An’ set her on the pad,

Got on afore her an’ set aff

As though they baith were mad!

They climb’d the braes—they lap the burns—

An’ through the glush did plash:

They never minded stock nor stane,

Nor ony kind o’ trash!

As they were near their journey’s end

An’ scudden through the glen:

“Oh!” says the Mammy to the ghaist,

“Are we come near the den!

For oh! I’m feared we meet the ghaist!”

“Tush, weesht, ye fool! “quo’ he;

“For waur than ye ha’e i’ your arms,

This nicht ye winna see!”

When they cam to the farmer’s door

He set the Mammy down:—

“I’ve left the house but ae half hour—

I am a clever loon!

But step ye in an’ mind the wife

An’ see that a’ gae richt,

An’ I will tak ye hame again

At twal’ o’ clock at nicht!”

“What maks yer feet sae braid?” quo’ she,

“What maks yer een sae sair?”

Said he, — “I’ve wander’d mony a road

Without a horse or mare!

But gin they speir, wha’ brought ye here,

‘Cause they were scarce o’ men;

Just tell them that ye rade ahint

The ghaist o’ Ferne-den!”

References:

- Guthrie, James C., The Vale of Strathmore – Its Scenes and Legends, William Paterson: Edinburgh 1875.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian