Cross: OS Grid Reference – SE 88923 98686

Also Known as:

- Lilla’s Cross

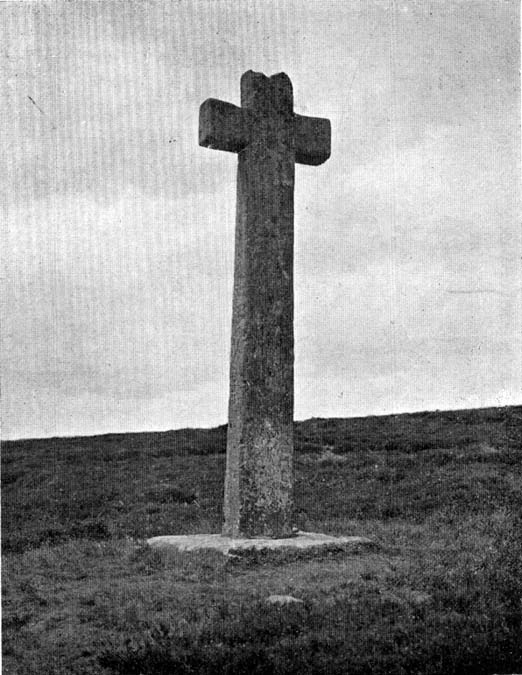

Lilla Cross is situated on Fylingdales Moor, north Yorkshire, between Pickering and Whitby at the junction of two major moorland footpaths. It is located close to the Fylingdales Ballistic Missile Early Warning Station – which resemble giant golf balls on the horizon.

Archaeology & History

The ancient cross is 10 foot high and free-standing but it sits upon what is probably a ruined Bronze-Age bowl barrow called Lilla Howe; the recumbent stones that lie around the base of the cross may form part of that. It is a sturdy, stocky cross that has some letters carved onto it, one in particular being a large letter “C” possibly meaning Christos (Christ) and with that a small thin cross; there are a few other faint letters but these are difficult to decipher now. A plaque on a nearby stone gives information about the cross. I think Lilla Cross was used as a sort of Medieval milestone or way-marker – hence the lettering on the cross.

In 1952 the cross was moved to Sil Howe near Goathland but 10 years later in 1962 it was returned to its original site on top of Lilla Howe. In the 1920s excavations on the barrow revealed some artefacts of jewellery, but no remains of Edwin’s trusty chief minister were found; the jewellery was, in fact, said to date from the mid 9th century. Lilla Cross has been referred to by historians as the oldest christian cross on the north York Moors.

Folklore

According to the legend, in AD 625 or 626 King Edwin of Northumbria was travelling with his entourage across the moors, but an assassin had been dispatched by the king of the west Saxons to kill Edwin. The assassin lunged forward with his poison tipped sword, but Lilla his chief minister at the king’s court, leapt in between his sovereign and the swordsman. Poor Lilla took the full thrust of the sword and died on the spot thus saving the king from being murdered. King Edwin, who was greatly impressed by this selfless act of devotion, ordered that Lilla being a newly converted christian be buried here in a christian way though he asked that a number of articles be placed with the body including gold and silver. The king then had a cross erected in memory at the spot where Lilla died. But it seems likely that the cross dates from the 10th century, though there may have been an earlier Saxon cross here.

References:

- Ogilvie, Elizabeth & Sleightholme, Audrey, An Illustrated Guide to the Crosses on the North Yorkshire Moors, Village Green Press: Thorganby 1994.

- White, Stanhope, Standing Stones and Earthworks on the North Yorkshire Moors, Fretwell & Cox: Keighley 1987.

- Woodwark, T.H., The Crosses on the North York Moors, Whitby Literary & Philosophical Society 1934.

© Ray Spencer, 2011