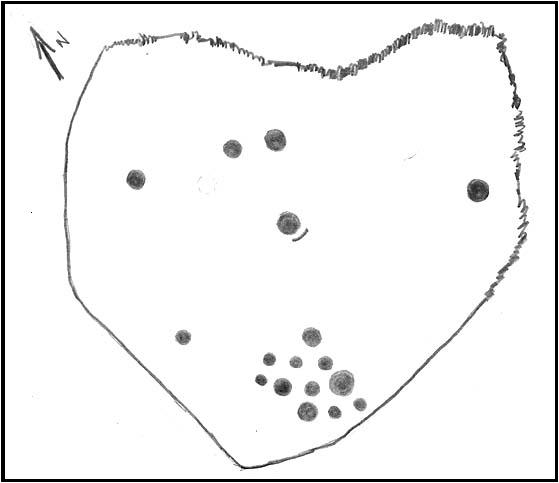

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 07366 44628

Also Known as:

- Carving no.10 (Hedges)

- Carving no.49 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Getting Here

A wonderful site, though a bittova walk for city-minded folk. Head up the road from Riddlesden, Keighley, towards the southern edge of Rombalds Moor and keep going till you reach the road which surrounds the moor (called Silsden Road). At the T-junction in front of you is a path which takes you onto the fields and moor. Go over the stile and walk straight up the steepish field that follows the straight line of the forest, all the way to the top. Climb over the wall on your left when you reach the top of the tree-line, walk past the triangulation pillar for 100 yards or so till you hit the end of the walling before it drops back into the trees. The carving’s under your nose!

Archaeology & History

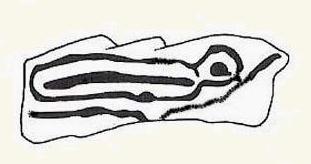

The name of this carving is based on a first impression I got of it when I came here as a young lad, still in my teens. The ‘Wondjina’ is a name given to primal aboriginal spirits whose images are etched and painted on rock surfaces in various parts of Australia (usually rock overhangs or in caves). Don’t ask me why, but that was the impression I first got of this stone — and it’s something that stays with me. Some archaeo’s won’t like the association such mythic ancestral beings may have upon people’s notions of cup-and-ring art, but they tend to be the ones who have little educational background regarding the animistic nature of rocks in traditional and peasant societies: ingredients that are integral to these ancient carvings, as research worldwide clearly shows.

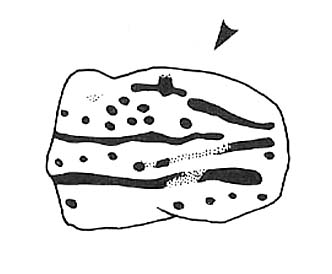

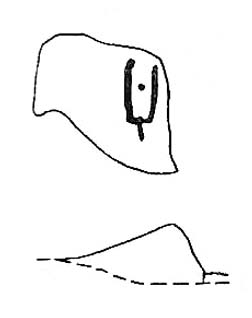

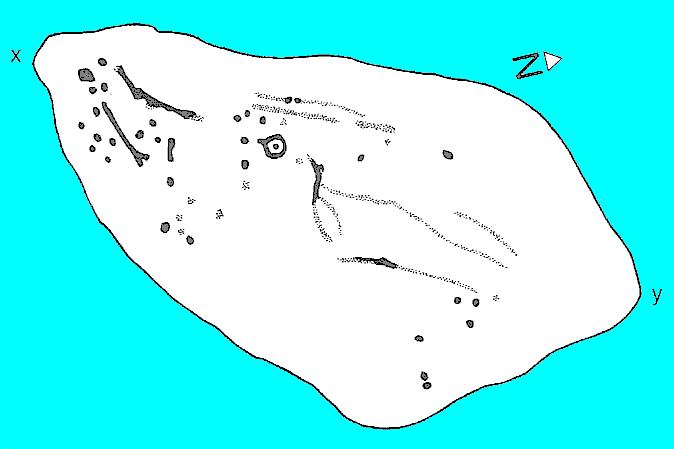

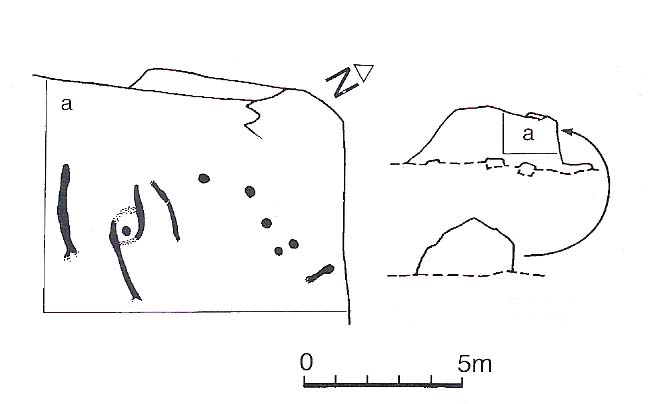

The carving was first described by our old Yorkshire historian Arthur Raistrick (1936) in an early essay on Yorkshire rock carvings; and then again in a later article by Stuart Feather. (1961) The primary design is of a large single cup-and-ring at one end of the rock, with a series of seemingly unbroken lines reaching up (or perhaps moving away) from the cup-and-ring. A long central line runs through the middle of the Wondjina ‘being’, which initially seems to have been a series of cups linked by this line; though these cups (at least four of them) have eroded over time and are difficult to see without good sunlight. What seem to be several other very eroded cup-marks are also found on two of the other long lines. These can be made out in the photograph here.

Another carving is on the stone right next to this one (2ft away) and there are several other cup-marked stones to be found along the same ridge (carving numbers 058, 059, 060, etc). And for those of you into landscape archaeology, take the position of this carving into consideration. The view from here is quite superb and on clear days a number of prominent hills and important mythological landscape features stand out. To those of you who think such things unimportant or of little relevance in the mythography of our ancestors — you’ve a lot to learn! Otherwise, a visit to this carving and its associates is well worth a trek!

References:

- Bennett, Paul, ‘The Prehistoric Rock Art and Megalithic Remains of Rivock & District (2 parts),’ in Earth, 3-4, 1986.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS 2003.

- Feather, Stuart, ‘Mid-Wharfedale Cup-and-Ring Markings: Nos. 7 & 8, Rivock Edge,’ in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 6:8, 1961.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Raistrick, Arthur, “‘Cup-and-Ring’ Marked Rocks of West Yorkshire,’ in Yorkshire Archaeology Journal, 32, 1936.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian