Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 14250 81756

Also Known as:

-

WAP 8 (Brown & Brown)

Getting Here

From Masham, head westwards along the country lanes to Fearby village (passing the old cross on the green), through old Healey village (where once stood four stone circles, seemingly destroyed) and onwards to Gollinglith. From here, keep going up the winding steep lane until you’re at the top where, on the right-hand side of the road, a footpath takes you diagonally northwest over the uphill fields. When you hit the walling which leads to the woods, follow it up and, once at the corner of the trees, follow the track back eastwards along the wall edge, keeping your eyes peeled when you pass the second line of walling that runs down the slope. You’re damn close!

Archaeology & History

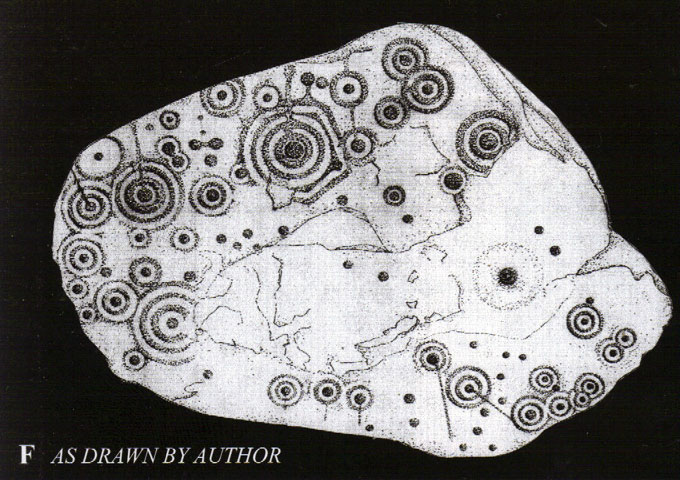

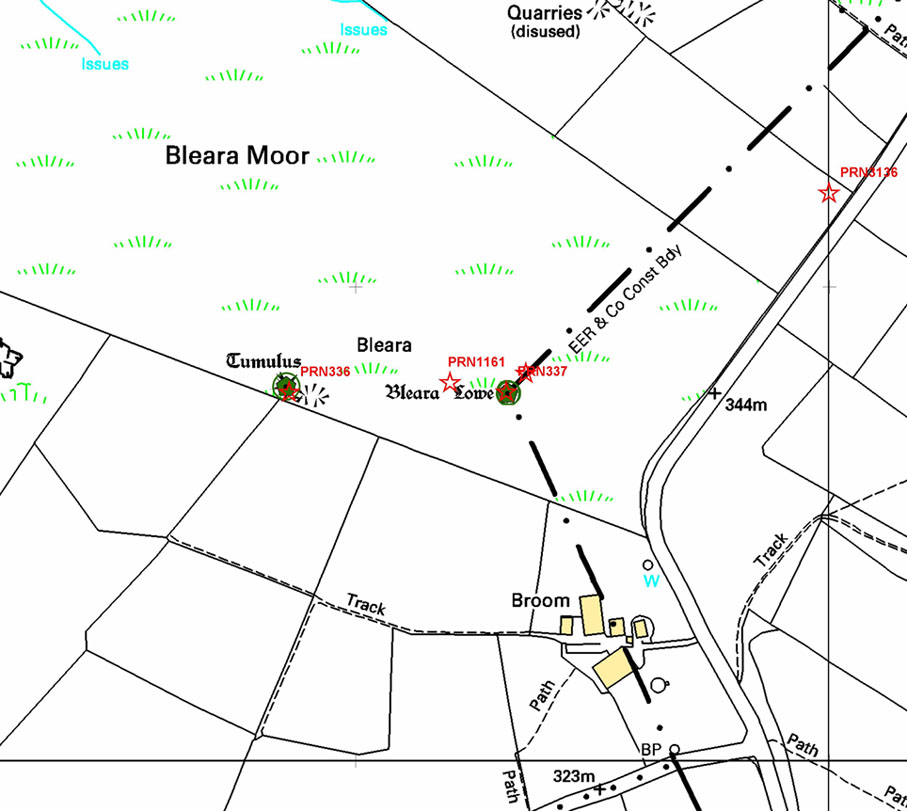

One of a cluster of fascinating carvings in this remote region of the upland Dales, this is perhaps the most impressive multiple-ringed carving of the group, known collectively as the West Agra Plantation group. The carving was rediscovered sometime in 2002 by Emily McIntosh and was described by Brown & Brown (2008) thus:

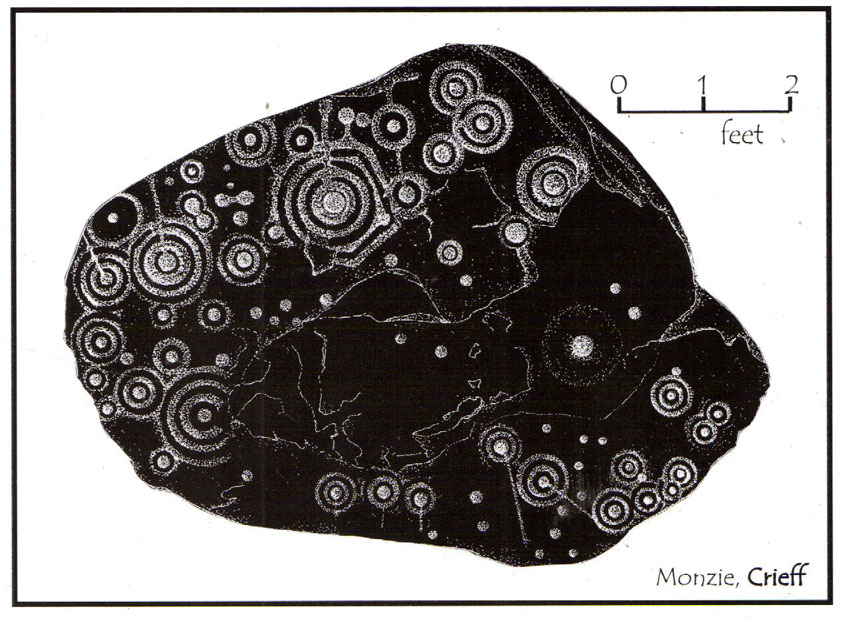

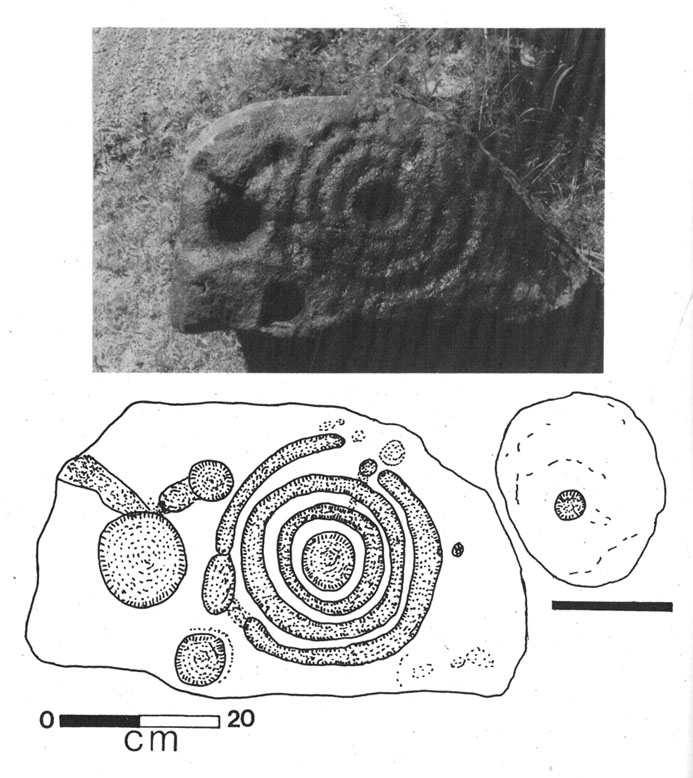

“This boulder measures 5.5 x 3.1 x 1.28m and has a multiringed motif 50cm in diameter linked by a number of grooves and isolated cups.”

But this barely does the stone justice. The main focus is on the cup with six surrounding rings, intersected by an intrusive double-line from outside the series of rings then running into the central ring itself — though not touching the focal cup at the very centre. This double line points to the southeast and is somewhat akin to a sliver of light running to or from old solar designs. It is a little bit like some aspects of the carved stones found on Ilkley’s Panorama Stones (though Ilkley’s carvings are much fainter). At the end of the intrusive double-line is a small cluster of cup-marks. There’s also another curious singular carved line running outwards from the third ring, running out of the concentric rings then heading off further down the stone. More cups and lines scatter other parts of the stone and there may be another faint line running from near the central cup all the way out of the rings close to the main ‘ray’ of lines.

A large standing stone can be seen if you walk a few hundred yards east along the side of the wall. It’s quite impressive.

Apparently the woodland in which this carving (and its associates) can be found is supposedly ‘private’ and one is supposed to contact some group calling itself Swinton Estates to set foot in the woods. Not the sort of practice we usually put up with in Yorkshire. If anyone has their contact details, please add them below in the event that anyone has need to ask ’em about going for a walk here.

References:

- Brown, Paul & Barbara, Prehistoric Rock Art in the Northern Dales, Tempus: Stroud 2008.

Links:

- Agra Wood Rock Art – more notes & images

Acknowledgements: For use of their photos, many thanks to Geoff Watson; and QDanT and his Teddy!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian