Tumulus (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – TA 0584 6128

Archaeology & History

A fallen tumulus that once marked the southwestern side of the village boundary line, and was once adjacent to the prehistoric Green Dikes earthworks that once passed here. Sadly however, sometime early in the 20th century, this ancient burial mound fell victim to usual ignorance of arrogant land-owners who place money ahead of history and local tradition and it was ploughed-up and destroyed. Thankfully we have an account of the site in J.R. Mortimer’s (1905) incredible magnum opus. Listing it as ‘Barrow no.272’ in the number of tombs excavated, he told us that:

“It is situated on elevated ground about half-a-mile (south)west of Ruston Parva. On September 20th and 21st, 1886, it measured about 70 feet in diameter and 2 feet in elevation; and had originally been several feet higher, as an old inhabitant remembered assisted in removing its upper portion, which was carried away and spread on the surrounding land many years previously. At the base of the barrow, near the centre, was a long heap of cremated bones which had been interred in a hollow log of wood with rounded ends, about 3 feet in length and 14 inches in width, well shown by impressions in the plastic soil, and by the remains of the decayed wood. The heap of bones was rather large and probably consisted of the remains of more than one body. No relic accompanied them. Several splinters and flakes of flint were picked from the mound.”

The tumulus (as its name implies) became a spot besides which one of East Yorkshire’s many ancient beacons were built. In Nicholson’s (1887) survey of such monuments, he told that

“the modern beacon, apparently, stood on the site of the old one, on the high ground in the angle of the road from Driffield to Kilham. It was a prominent object and would be well-known to the coachmen and guards…for it stood on the side of the road from Driffield to Bridlington. Mr John Browne, of Bridlington, remembers it; and says, ‘It would be the last of the beacons that remained in this district and was removed between fifty and sixty years ago. My recollection of it is that it was a tall pole, with a tar barrel at the top, and had projected steppings to reach the barrel.”

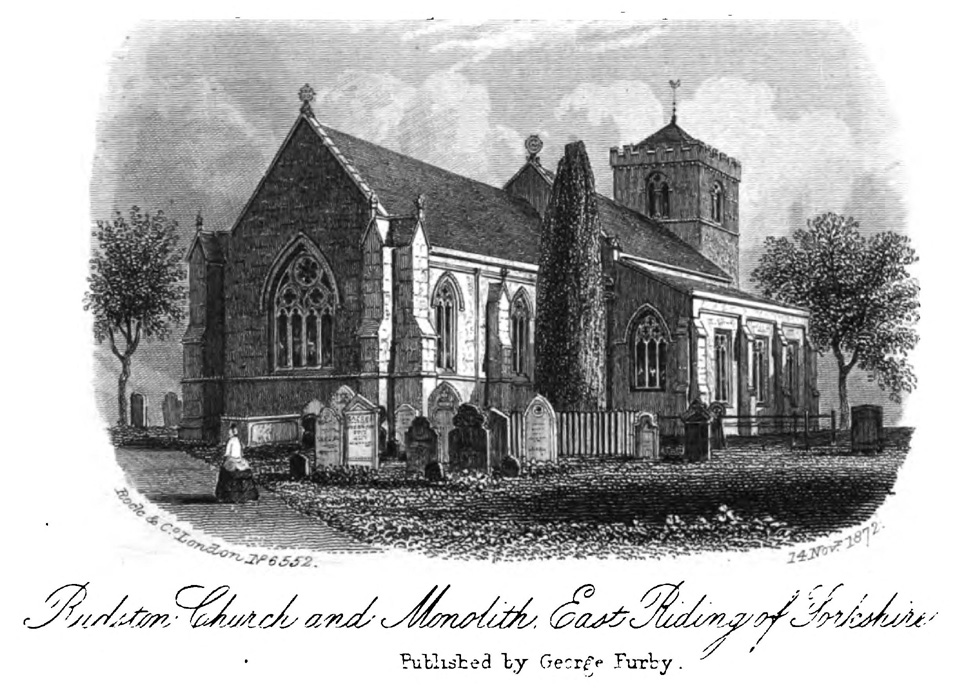

One of the earliest accounts of the beacon from the late-1500s told that it took signal for its light from the beacon at Rudston, which stood upon one of the Rudston cursus monuments, a short distance from the massive Rudston monolith.

References:

- Mortimer, J.R., Forty Years Researches in British and Saxon Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire, Brown & Sons: Hull 1905.

- Nicholson, John, Beacons of East Yorkshire, A. Brown & Sons: Hull 1887.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian