Standing Stones: OS Grid Reference – NS 73609 46916

Also Known as:

- Avonholm

- Canmore ID 45595

- Glesart Stones

- Struthers Burial Ground

- Three Stones

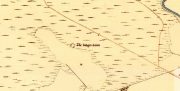

Glesart Stones on 1864 map

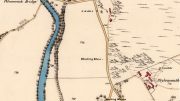

From the roundabout in Glassford village, head west down Jackson Street along the country lane of Hunterlees Road. About 600 yards on, turn right at the small crossroads (passing the cemetery on yer left) for about half-a-mile, before turning left along a small track that head to some trees 400 yards along. Once you’ve reached the trees, walk uphill and follow the footpath to the right, keeping to the tree-line. It eventually runs to a small private graveyard. You’re there!

Archaeology & History

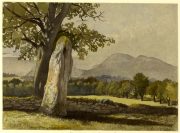

Glesart Stones,

looking west

In the little-known private graveyard of the Struthers family on the crest of the ridge overlooking the River Avon and gazing across landscape stretching for miles into the distance, nearly a mile east of Glassford village, several hundred yards away from the Commonwealth graveyard, a cluster of yew trees hides, not only the 19th century tombstones, but remnants of some thing much more archaic. Three small standing stones, between 2½ and 4 feet in height, hide unseen under cover of the yews, at the end of a much overgrown ancient trackway which terminates at the site. They’re odd, inasmuch as they don’t seem to be in their original position. Yet some form of archaic veracity seems confirmed by the weathered fluting: eroded lines stretching down the faces of two of the taller stones and, more importantly, what seem to be cup-markings on each of the monoliths.

Cup-mark atop of east stone

Easternmost stone

The tallest stone at the eastern end of the graveyard has a deep cup on its crown. This may be the result of weathering; but we must exercise caution with our scepticism here. Certainly the eroded lines that run down this stone are due to weathering – and many centuries of it; but the peculiarity is that the weathering occurs only on one side. This implies that only one side of the stone was open to the elements.

Central cup-marked stone

‘X’ carved atop of central stone

The second, central stone of the three, is slightly smaller than the first. Unlike the eastern stone, its crown has been snapped off at some time in the past century or so, as evidenced in the flat smooth top. But along the top are a series of small incised marks, one of which includes a notable ‘X’, which may have been surrounded by a circle. A second fainter ‘X’ can be seen to its side, and small metal-cut lines are at each side of these figures. Another small section of this stone on its southern edge has also been snapped off at some time in the past. The most notable element on this monolith is the reasonably large cup-mark on its central west-face. It is distinctly eroded, measuring 2-3 inches across and an inch or more deep. Its nature and form is just like the one in the middle of the tallest of the standing stones at Tuilyies, nearly 31 miles to the northeast.

Western smallest stone

The Three Stones

The smallest of the three stones is just a few feet away from the central stone. To me, it seemed oddly-placed (not sure why) and had seen the attention of a fire at its base not too long ago. On its vertical face near the top-centre of the stone, another cup-marking seems in evidence, some 2 inches across and half-an-inch deep—but this may be natural. The Glasgow archaeologist Kenneth Brophy reported that on a recent visit, computer photogrammetry was undertaken here, so we’ll hopefully see what they found soon enough.

There is some degree of caution amongst some archaeologists regarding the prehistoric authenticity of the Glesart Stanes – and not without good cause. Yet despite this, the seeming cup-marks and, particularly, the positioning of the stones in the landscape suggest something ancient this way stood. The stones here are more likely to be the remains of a once-larger monument: perhaps a cairn; perhaps a ring of stones; or perhaps even an early christian site. At the bottom of the hill for example, just 350 yards below, is a large curve in the River Avon on the other side of which we find the remains of an early church dedicated to that heathen figure of St. Ninian (his holy well close by); and 300 yards north is the wooded Priest’s Burn, whose history and folklore seem lost.

The Glesart Stanes were the subject of an extended article by M.T. M’Whirter in the Hamilton Advertiser in 1929 (for which I must thank Ewan Allinson for putting it on-line). He wrote:

“Situated on the highest hill-top on the estate of Avonholm, north to the house of that name, is the private burial ground of James Young Struthers… Situated within the burial ground are three upright flagstones of a dark brown colour, rough and unhewn, Each stone is facing the east, and placed one behind the other, though not in a straight line, and the space between the eastern and the middle stone is eight feet, and the space between the middle and the western stone is seven feet. The stone flags vary in measurement, the eastern stone being the greater, standing four feet three inches high, three feet eight inches broad, and one foot thick. The middle stone is three feet high, three feet ten inches broad, and nine inches thick; and the western stone is three feet high, four feet broad and ten inches thick. The two outer stones bear no letters, figures or marks, but the centre stone has rudely sculptured on the top-edge the Roman numerals IX, and on the western side of the stone there is a cup-shaped indentation about two inches in diameter. A groove 26 inches in length extends from the top of the stone to below the level of the cup indentation. The groove is deeper at the top, but gradually loses in depth towards the bottom end. I have seen grooves similar to above by the friction of a wire rope passing over a rocky surface. The numerals, cup indentation and groove do not appear to be part of the original placing of the stones and, if a cromlech, then in the centuries that have gone, the stones becoming exposed to view by the removal of the mound, would invariably have led to a search for stone coffins or urns, yet no discovery of either has ever been recorded.”

Indeed, Mr M’Whirter was sceptical of them being part of a prehistoric burial site, preferring instead to think that a megalithic ring once stood here. He continued:

“From an examination of the three stones, I am convinced that they form a segment of a circle, and assuming that nine additional stones complete the circle, it would enclose a space of roughly one hundred feet in circumference, with each stone facing an easterly direction.”

But we might never know for certain…. The only other literary source I have come across which describes the site is that by the local vicar, William Stewart (1988), who told us that:

“The stones stand erect, six feet apart, three rough slabs of coarse-grained sandstone, three feet high, three feet broad and six inches thick, free of any chisel marks. Two have their back to the east, the third, oblique to the others, has its back to the south-east, thus there is no suggestion of a stone circle. There are vertical grooves on two of the stones, while the centre stone has a cupmark, below which is a faint circle, one foot in diameter. They stand at the end of a long narrow strip of land with low earthen walls on either side, perhaps an old agricultural field division, and they gave their name ‘Three Stanes’, to a now partly-lost road which eventually reached The Craggs and ended as Threestanes Road in Strathaven…”

The Three Stones

The “faint circle” described by Mr Stewart is barely visible now. And the idea that these “three stones” gave their name to the farmhouse and road of the same name at the other side of Strathaven, three miles west, seems to be stretching credulity to the limits. Surely?

Folklore

In 1845, Gavin Laing in the New Statistical Account for Lanarkshire told that:

“These stones are known simply as the “Three Stones”. There is a tradition in the neighbourhood that three Lords were buried here, after being killed while looking on at a Battle. The stones are about 3½ feet high and about as thick as flag stones. They stand upright being firmly fixed in the ground.”

The stones and their traditional origin were also mentioned in Francis Groome’s Ordnance Gazetteer (1884), where he echoed the 1845 NSA account, but also added:

“Three tall upright stones are here, and have been variously regarded as Caledonian remains, as monuments of ancient noblemen, and as monuments of martyrs.”

Then at the end of the 1850s, when the Ordnance Survey lads came here, they reported,

“Three high stones stand upright on a small eminence upon the lands of Avonholm, respecting their origin there are various opinions. They are probably the remnants of Druidical superstition.”

References:

- Groome, Francis H., Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland – volume 1, Thomas C. Jack: Edinburgh 1884.

- M’Whirter, M.T., “The Standing Stones at Glassford,” in Hamilton Advertiser, 1929.

- Stewart, William T., Glasford – The Kirk and the Kingdom, Mainsprint: Hamilton 1988.

- Wilson, James Alexander, A Contribution to the History of Lanarkshire – volume 2, J. Wylie: Glasgow 1937.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian