Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 0092 4756

Also Known as:

- Black Hill Long Barrow

- Bradley Moor Long Barrow

- Bradley Moor Long Cairn

- King’s Cairn

Follow the same directions for getting to the Black Hill Round Cairn. It’s less than 100 yards away – you can’t miss it!

Archaeology & History

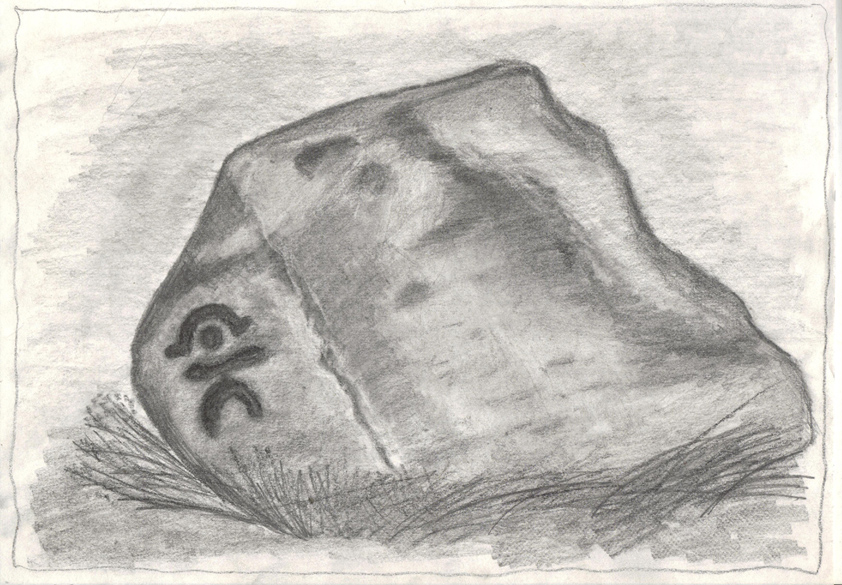

This is a superb archaeological site — and it’s bloody huge! It’s big and it’s long and it sticks out a bit – which is pretty unique in this part of the Pennines, as most other giant cairns tend to be of the large round variety. Although the site was originally defined by Arthur Raistrick (1931) as a long barrow, J.J. Keighley (1981) told how, “it was found to be a round cairn imposed on a long cairn.” And it’s an old one aswell…

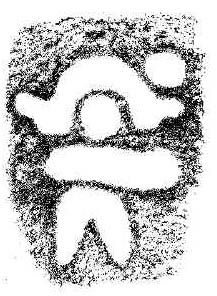

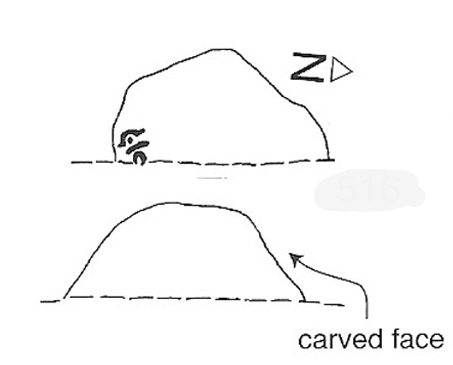

More than 220 feet long and 80 feet in diameter at its widest southeastern end, as we walk along the length of the cairn to its northwestern edge, its main body averages (only!) 45 feet in diameter. Made up of tens of thousands of rocks and reported by Butterfield (1939) to have had an upright stone along its major axis, the “height varies from 4-8ft, but the cairn has been much despoiled and disturbed,” said Cowling in 1946. He also told how,

“Excavation revealed that almost in the centre of the mound were the remains of a cist made of roughly dressed stone flags and dry walling, covered by a large stone. Under a stone slab, laid on the floor of the cist, were fragments of (burnt and unburnt) bone and a small flint chipping.”

This is a very impressive site and deserving of more modern analysis. The alignment of the tomb, SE-NW, was of obvious importance to the builders, believed to be late-neolithic in character. The tomb aligns to two large hills in the far distance in the Forest of Bowland which we were unable to identity for certain. If anyone knows their names, please let us know!

Folklore

The older folk of Bradley village below here, tell of the danger of disturbing this old tomb. In a tale well-known to folklorists, it was said that when the first people went up to open this tomb for the very first time, it was a lovely day. But despite being warned, as the archaeologists began their dig, a great storm of thunder, lightning and hailstones erupted from a previously peaceful sky and disturbed them that much that they took off and left the old tomb alone. (I must check this up in the archaeo-records to see if owt’s mentioned about it.)

References:

- Ashbee, Paul, The Earthen Long Barrow in Britain, Geo Books: Norwick 1984.

- Butterfield, A., ‘Structural Details of a Long Barrow on Black Hill, Bradley Moor,’ in YAJ 34, 1939.

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey, I, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Raistrick, Arthur, ‘Prehistoric Burials at Waddington and Bradley,’ in YAJ 30, 1931.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian