Cup-Marked Stone (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NT 1273 6973

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 50366

- Witch’s Stone

Archaeology & History

This fascinating looking carving (in my personal Top 10 of all-time favourites cup-and-rings in the UK!) was unfortunately destroyed sometime between 1918 and 1920. A huge pity, as the design on the rock is almost unique in its ‘linear’ system of cups running a considerable length across the surface of the stone (like the similar design found at Old Bewick in Northumberland).

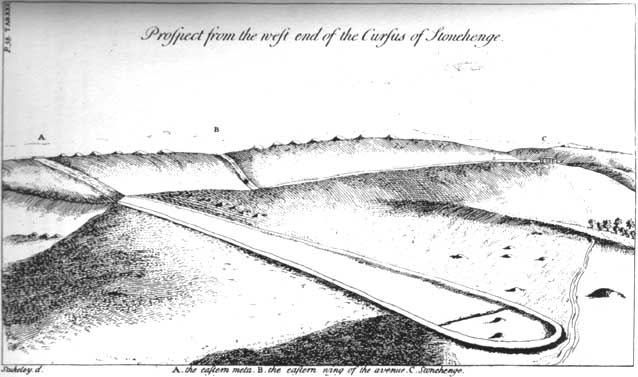

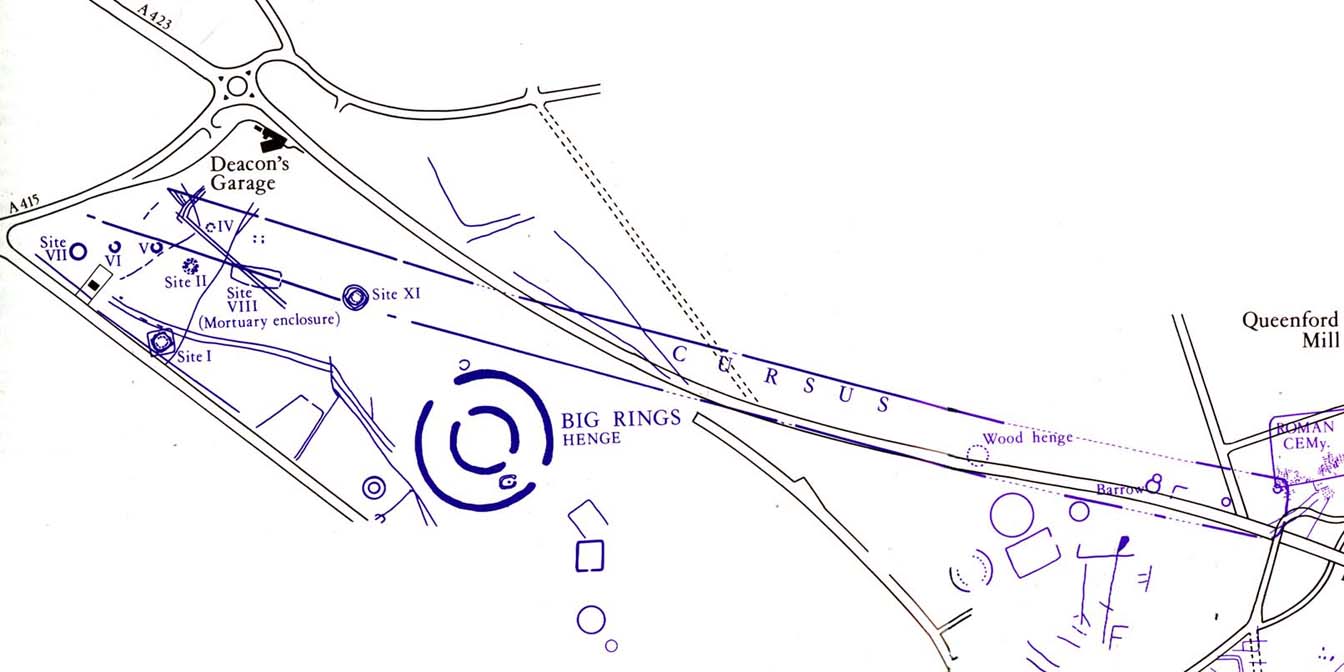

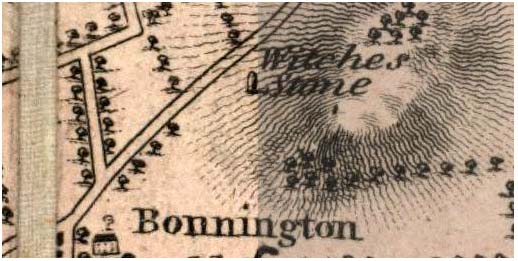

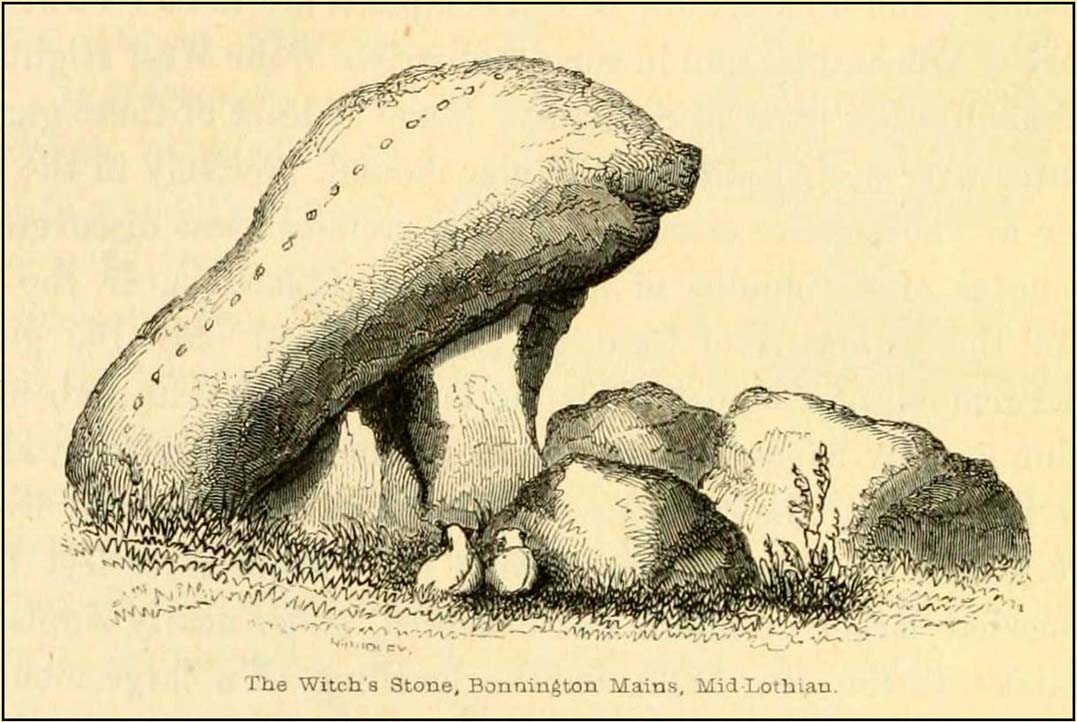

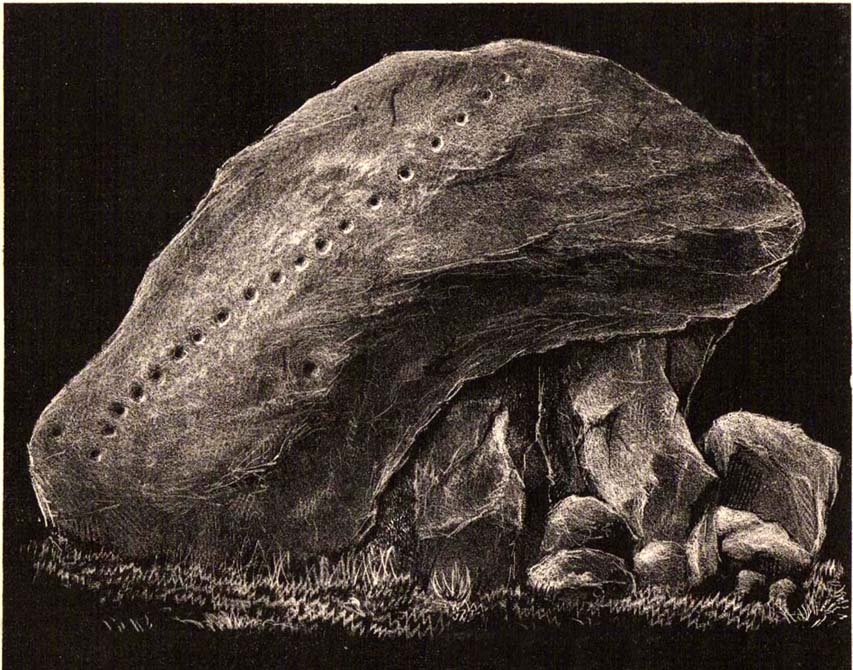

Shown first of all on Kirkwood’s Environs of Edinburgh map in 1817 (above), this legendary rock was found amidst a cluster of other cup-and-ring stones at Tormain (some are still there) and was initially said by Daniel Wilson (1851) to have been the giant capstone of a cromlech that once stood here, but whose structure had fallen away. This idea is implied in the earliest drawing we have of the stone in Wilson’s magnum opus (above); Sir J.Y. Simpson (1867) gave us a similar impression with his drawing a few years later. But upon visiting the Witches Stone just as his book was going to the press, Mr Wilson visited the site and proclaimed that he “altogether doubted if they are the remains of a cromlech”, and what rested here were more probably just fascinating geological remains, with even more fascinating carvings on top!

In the years that followed Wilson’s initial description, the Witches Stone was visited and described by a number of eager antiquarians. Simpson (1867) gave us a quite revealing account, telling:

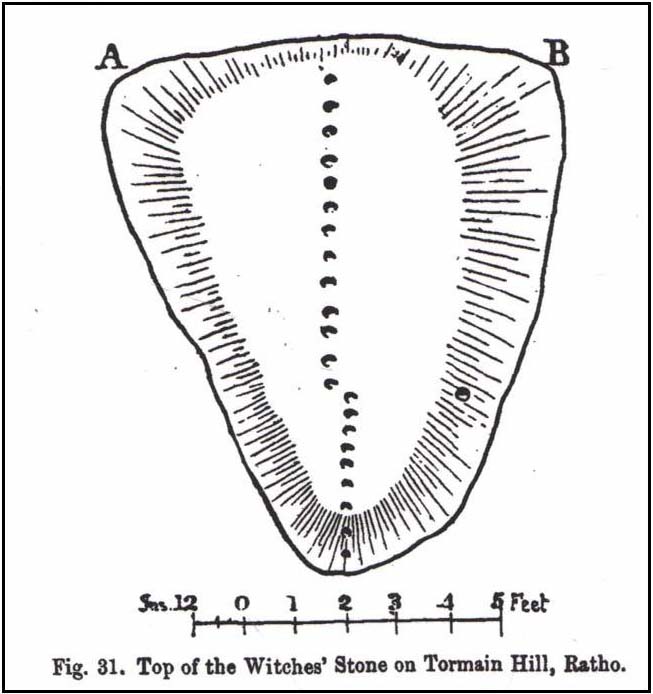

“On the farm of Bonnington, about a mile beyond the village of Ratho…are the remains of ‘this partially ruined cromlech’…with the capstones partially displaced, as if it had slid backwards upon the oblique plane of the huge stones or stone which still supports it. Two or three large blocks lie in front of the present props. Its site occupies a most commanding view of the valley of the Almond, and of the country and hills beyond. The large capstone is a block of secondary basalt or whinstone, about twelve feet long, ten in breadth and two in thickness. Its upper surface has sculptured along its median line a long row of some twenty-two cup-cuttings; and two more cup-cuttings are placed laterally: one, half a foot to the left of the central row and at its base; the other, two feet to the right of the tenth central cup and near the edge of the block. The largest of the cups are about three inches in diameter and half an inch in depth; but most of them are smaller and shallower than this…”

A few years later another early petroglyph authority, J. Romilly Allen (1882), visited the Witches Stone and found “an Ordnance bench mark (had been) cut on the stone itself”! He then continued with his own description of this once-important megalithic site:

“The Witch’s Stone is a natural boulder of whinstone, rounded and smoothed by glacial action, whoso upper surface slopes at an angle of about 35° with the horizon. The length of the sloping face is 8 feet and at the top is a flat place 2 feet wide. The breadth of the stone is 11 feet 3 inches at the upper end, and 4 feet at the lower end. The thickness varies from 2 to 3 feet. The highest part of the stone is 6 feet 6 inches above the ground, and the lowest 1 foot 6 inches. It rests on what has originally been a portion of the same boulder, but is now a mass of whinstone broken up into several fragments, which serve as supports to prop up the stone above. Viewed from the north side the whole presents the appearance of a cromlech, the upper stone forming the cap, and the disintegrated portion below the supports. This notion, however, will be clearly seen to be erroneous on looking at it from the opposite side, as shown on the accompanying sketch…where the crack separating the two portions of the boulder is very apparent… The sculpturings consist of twenty-four cups varying in diameter from 1½ to 3 inches. Twenty-two of these cups are arranged in an approximately straight line along the sloping face of the stone, and divide it into two almost equal parts. The two remaining cups lie, one 7½ inches to the left of the lowest cup of the central row, and the other 2 feet 3 inches to the right of the ninth cup up the stone… The field in which the Witch’s Stone is situated is called “Knock-about.” The sloping face of the stone has been much polished by the practice of people climbing on to the top and sliding down. Some of the cups are almost obliterated in consequence. The stone forms a very prominent feature in the view, and must always have attracted attention from its peculiar shape.”

Some twenty years after Allen, the megalithomaniac Fred Coles (1903) came and checked the Witches Stone out for himself and, as happens, had a few additional things to say about the place:

“Although this huge boulder and its cup-marks have been more than once figured and described, I found, on a close examination of the broad surface of the Stone, that none of the illustrations showed the cup-marks in their exact relation to each other, nor in their true relation to the contour of the Stone. The drawing shown above…was made after a careful measurement by triangulation of the Stone; and it is claimed to be the first that shows that the cups, two and twenty in number, are not disposed in one continuous line, but that thirteen follow each other from the high south edge of the stone for a distance of exactly 6 feet, and nine others lie a few inches to the west, occupying a space 3 feet long of the overcurving edge of the north end. It is further shown that, at a point 2 feet 3 inches west of the ninth cup-mark, there is another one quite as large as the largest in the rows near the middle of the Stone. The south edge (A B) has slipped a little down from its original height, the boulder being frost-split horizontally; its height there above ground is 8 feet. The northern and narrower end is about 2 feet above ground, and does not touch the ground, as it rests upon its lower portion, beyond which it projects a few inches. The cup-marks run due north.”

If the Witches Stone was in fact a natural outcrop stone and not a cromlech, this very last point telling that “the cup-marks run due north” probably had much greater importance than a mere compass-bearing to the people who etched this carving. For in pre-christian religious structures across the northern hemisphere, north is commonly representative of death and the land of the gods. In magickal rites “it is the place of greatest symbolic darkness,” as neither sun nor moon ever rise or set there. Additionally, north is the place where, in shamanic traditions, the heavens are tied to the Earth: the cosmic axis itself that links heaven, Earth and underworld. In early neolithic traditions this mythic structure was probably endemic. Whether its magickal relevance was intended here, at this stone, we will probably never know…

Folklore

Folklore tells that the Witches Stone was one of the sites used in magickal rites by the Scottish occultist, Michael Scot. J.R. Allen’s (1882) description of “the sloping face of the stone has been much polished by the practice of people climbing on to the top and sliding down,” may relate to folk memory of fertility rites once practiced here, as found at similarly carved rocks in the UK and across the world.

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “Notes on some Undescribed Stones with Cup Markings in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 16, 1882.

- Coles, Fred R., “Notes on Some Hitherto Undescribed Cup-and-Ring Marked Stones,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 37, 1903.

- McLean, Adam, The Standing Stones of the Lothians, Megalithic Research Publications: Edinburgh no date (c.1978).

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Counties of Midlothian and West Lothian, HMSO: Edinburgh 1929.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Smith, John Alexander, “Notes of Rock Sculpturings of Cups and Concentric Rings, and ‘The Witch’s Stone’ on Tormain Hill; also of some Early Remains on the Kaimes Hill, near Ratho, Edinburghshire,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 10, 1874.

- Wilson, Daniel, The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, Sutherland & Knox: Edinburgh 1851.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian