Chambered Cairn (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SJ 266 223

Also Known as:

- Llanymynych Hill

- Llech y Wydhon

Archaeology & History

An exact grid-reference for this once-impressive chambered tomb is difficult as “nothing remains of this site at the present day” (Daniel 1950) and the majority of the hilltop itself (a prehistoric hillfort no less), has been turned into one of those awful golf courses which are still spreading like cancer over our ancient hills. It was obviously very close to the Shropshire border, as the folklorist Charlotte Burne (1853) said the grave was “on the Shropshire side of Llanymynech Hill,” perhaps placing it in the township of Pant. But traditionally it remains within Llanymynech, within and near the top of the huge hillfort and east of Offa’s Dyke.

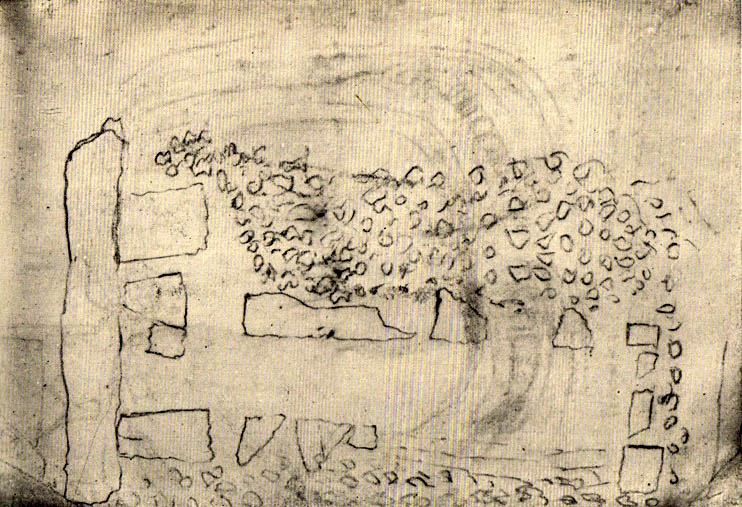

The old tomb was mentioned in an early letter of the great druid revivalist, Edward Lhwyd, who left us with the old ground-plan, reproduced above; and based on Lhwyd’s drawing and early narratives, Glyn Daniel (1950) thought the site “was perhaps a gallery grave”. The best description we have of Bedd y Cawy was penned by John Fewtrell (1878) in his essay on the local parish in which he told:

“This interesting relic of antiquity stood on the north-eastern end of the hill. It was formed of four upright stones, on the top of which was placed a flat slab measuring 7ft by 6ft, and 18 in thickness. It is known by the name “Bedd-y-Cawr” (the Giant’s grave). The British name appears to support the theory that the cromlech is a burying place, and not an altar devoted to religious purposes. The word is derived probably from the Welsh cromen, a roof, or vault, and lech, a stone, meaning a vault formed by a slab supported upon uprights ; or, according to some, ” the inclining flat stone”. Rowlands derives it from the Hebrew cærem-luach, “a devoted stone”, but this is far-fetched for a word or name in common use among our British forefathers. Many regard the cromlech as a distinct species of monument, differing from either a dolmen or a cairn.

“When the covering of stones or earth has been removed by the improving agriculturist, the great blocks which form the monolithic skeleton of the mound and its chamber usually defy the resources at his command. As the skeleton implies the previous existence of the organised body of which it formed the framework, so, upon this theory, the existence of a ‘ cromlech ‘ implies the previous existence of the chambered tumulus of which it had formed the internal framework. Sepulchral tumuli were formerly classified according to their external configuration or internal construction; but more extended and critical observation has shown that mere variations of form afford no clue to the relative antiquity of the structures. But as it has always been the custom of the prehistoric races to bury with their dead objects in common use at the time of their interment, such as implements, weapons, and personal ornaments, we have in these the means of assigning the period of the deposit relatively to the Stone, Bronze, or Iron age.” Sometimes no traces whatever of human remains are found in the chamber. Search was made to some depth in this cromlech, but nothing was found.”

In Fewtrell’s same essay he also described another megalithic site (also destroyed) on the southwestern part of the Llanymynech Hill, where,

“stood two rows of flat stones, parallel, 6 feet asunder, and 36 in length. A tradition exists which states that in digging near this place a Druid’s cell was discovered, but of what shape or size it does not relate. There were a number of human bones and teeth in a state of good preservation also discovered. In digging between the parallel rows a stratum of red earth was found, about an inch thick.”

Folklore

As the name of this old tomb tells, it was once reputed as “the Grave of the Giant”, but in Charlotte Burne’s huge work on the folklore of Shropshire (volume 1), she told it to be the tomb of his lady:

‘The Giant’s Grave’ is the name given to a mound on the Shropshire side of Llanymynech Hill, where once was a cromlech, now destroyed. The story goes that a giant buried his wife there, with a golden circlet round her neck, and many a vain attempt has been made by covetous persons to find it, undeterred by the fate which tradition says overtook three brothers, who overturned the capstone of the cromlech, and were visited by sudden death immediately afterwards.”

There is also a legendary cave beneath Llanymynech Hill which have long been regarded as the above of goblins and faerie folk. More of this will be told in the profile for the hillfort itself.

References:

- Burne, Charlotte Sophia (ed.), Shropshire Folk-lore, Trubner: London 1853.

- Daniel, Glyn E., The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales, Cambridge University Press 1950.

- Fewtrell, John, “Parochial History of Llanymynech,” in Collections Historical & Archaeological Relating to Montgomeryshire, volume 11, 1878.

- Wynne, W.W.E., “Letters of E. Lhwyd,” in Archaeologia Cambrensis, vol.3, 1848.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian