Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – NY 861 797

Archaeology & History

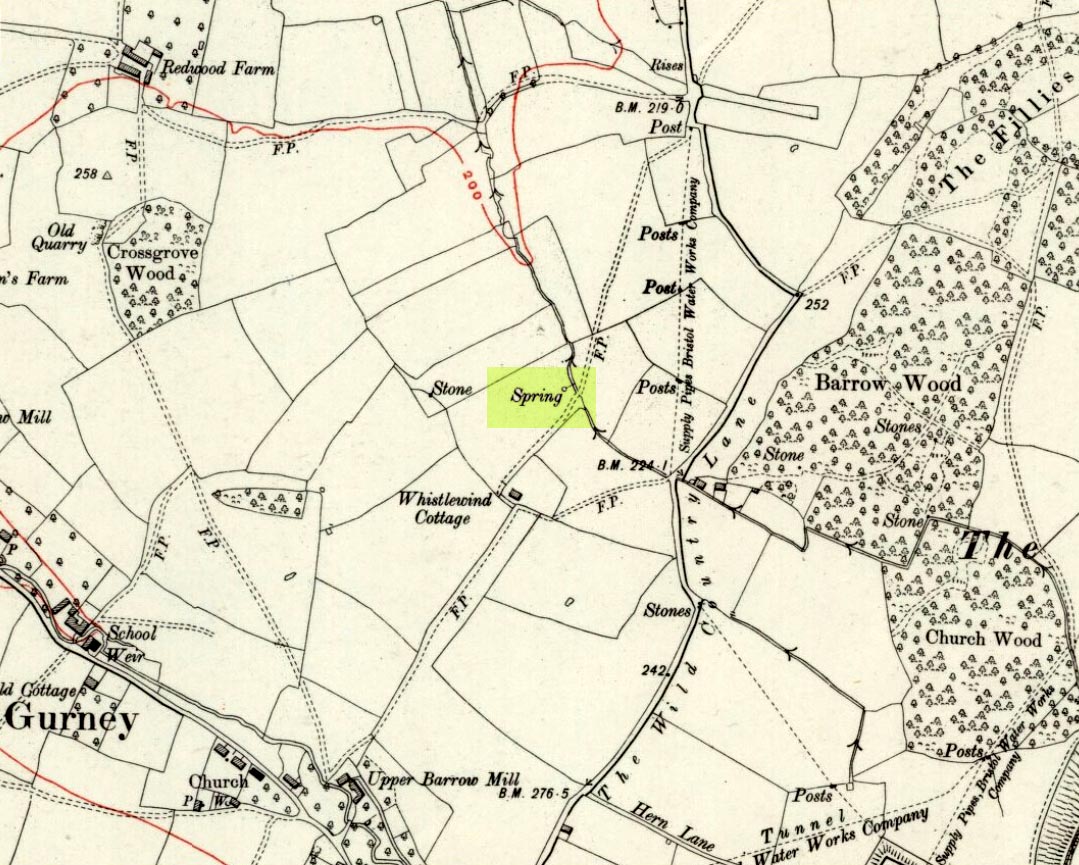

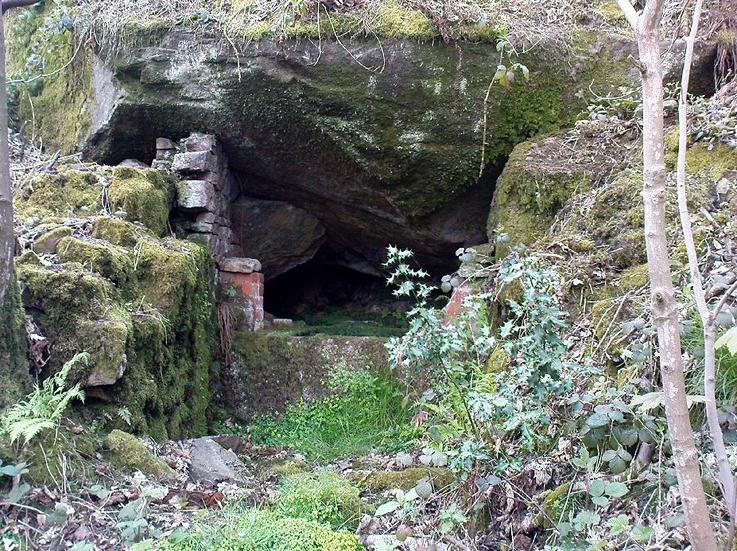

Very little is known about this forgotten heathen water source. It was described in some notes attached on a piece of paper accompanying John Warburton’s description of Lee Hall and its surroundings. The notes were first printed in an early edition of Archaeologia Aeliana and subsquently included in Binnall & Dodds’ (1942) fine survey on the holy wells of the region. It’s exact whereabouts appears to be lost, but it may be either the small pool across from the present Hall, or a small spring found in the edge of the small copse of trees just east of Lee Hall Farm. Does anyone know?

Folklore

Written verbatim in that dyslexic olde english beloved of antiquarians like misself, the only piece of folklore said of this spring of water told:

“At the Lee hall an exclent spring, the vertue is such that if the lady of the Hall dip aney children that have the rickets or any other groone destemper, it is either a speedy cure of death. The maner and form is as followeth: The days of dipping are on Whitsunday Even, on Midsumer Even, on Saint Peeter’s Even. They must bee dipt in the well before the sun rise and in the River Tine after the sun bee sett: then the shift taken from the child and thrown into the river and if it swim…child liveth, but if it sink dyeth.”

The latter sentence echoing the crazy folklore of the christians to identify witches in bygone days!

References:

- Binnall, P.B.G. & Dodds, M. Hope, ‘Holy Wells in Northumberland and Durham,’ in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (4th Series), 10:1, July 1942.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian