Stone Row: OS Grid Reference – SH 8767 6147

Also known as:

- Gwytherin Church Standing Stones

- The Four Stones

From the Denbigh road (A543 and A544) turn off at Llansannan for Gwytherin on the B5384 for 6 miles or so. At the village of Gwytherin St Winifred’s church stands roughly in the middle of the place at a junction of four roads. The church stands upon a small round hill and within the confines of the churchyard (north side) are four small standing stones – you can’t really miss them!

Archaeology & History

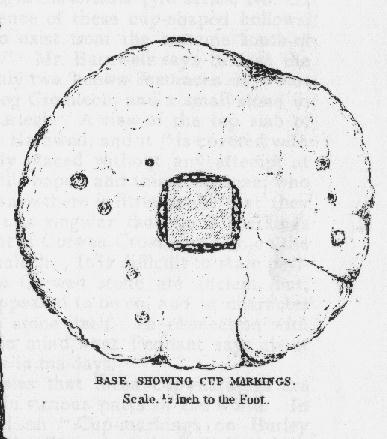

At the northern side of the churchyard near the wall there’s an alignment of four small standing stones probably dating from the Bronze Age. The stones stand roughly 3 metres or 6 feet apart and are about 1 metre or 3 feet in height. The westernmost stone has a Latin inscription carved onto it which is ‘VINNEMAGLI FILI SENEMAGLI’, or, ‘The Stone of Vinnemaglus, son of Senemaglus’, which is generally thought to date from the Romano-British period in the 5th-6th century AD and to be a grave marker. Most probably the inscription was carved onto the prehistoric stone during the early Christian period — the stones themselves being from pre-Christian times.

The general thinking is that these stones belonged to a Bronze Age settlement that stood here long before any church was founded. Perhaps there were other stones here forming a linear alignment that must have meant something to the ancient folks who lived here. There has also been speculation as to whether the inscribed standing stone could actually mark the grave of St Winifred herself.

The churchyard is circular, indicating that it is a pagan sacred site. Celtic churches being built on sites like this to Christianize them, but not entirely forget the meaning to the peoples of “the old religion,” as it’s called. Also in the churchyard stand three ancient yew trees — yet another sign that the site is a holy one.

The first church in Gwytherin was founded by St Eleri (Elerius), a Welsh prince, in the mid-7th century. He may be identical with St Hilary, a saint commemorated at a village of that name near Cowbridge, South Glamorgan. Other than that, Eleri and his mother, Theonia, founded a double monastery here: one for men and the other for women, to which a young St Winifred (of Holywell) came to and was elected second abbess after Theonia. St Eleri was probably a disciple of St Beuno, uncle to St Winifred, and also her cousin. Here in 650 or 670 AD Winifred was buried in the churchyard — her relics being taken to Shrewsbury abbey in 1138.

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, From Carnac to Callanish, Yale University Press 1993.

- Houlder, Christopher, Wales: An Archaeological Guide, Faber & Faber: London 1978.

- Hulse, T.G., Gwytherin: A Welsh Cult Site Of The Mid-Twelth Century, (unpublished paper) 1994.

- Nash-Williams, V.E., The Early Christian Monuments of Wales, Cardiff, 1950.

- Westwood, J.O., “Early Inscribed Stones of Wales,” in Archaeologia Cambrensis, 18:255-259, 1863.

Copyright © Ray Spencer 2011