Chambered Tomb (damaged) & Cup-and-Ring Stones: OS Grid Reference – SJ 405 875

Also Known as:

- Calder Stones

- Caldway Stones

- Dogger Stones

- Druid’s Cross

- Rodger Stones

Getting Here

Access to these stones has, over recent years been pretty dreadful by all accounts. It’s easy enough to locate. Go into Calderstones Park and head for the large old vestibule or large greenhouse. If you’re fortunate enough to get one of the keepers, you may or may not get in. If anyone has clearer info on how to breach this situation and allow access as and when, please let us know.

Archaeology & History

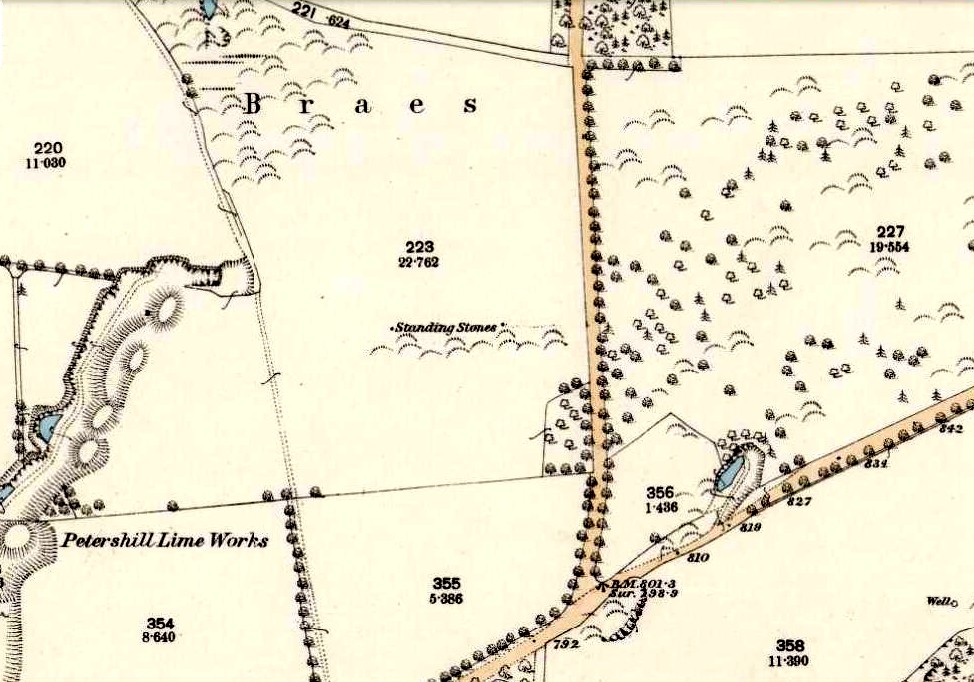

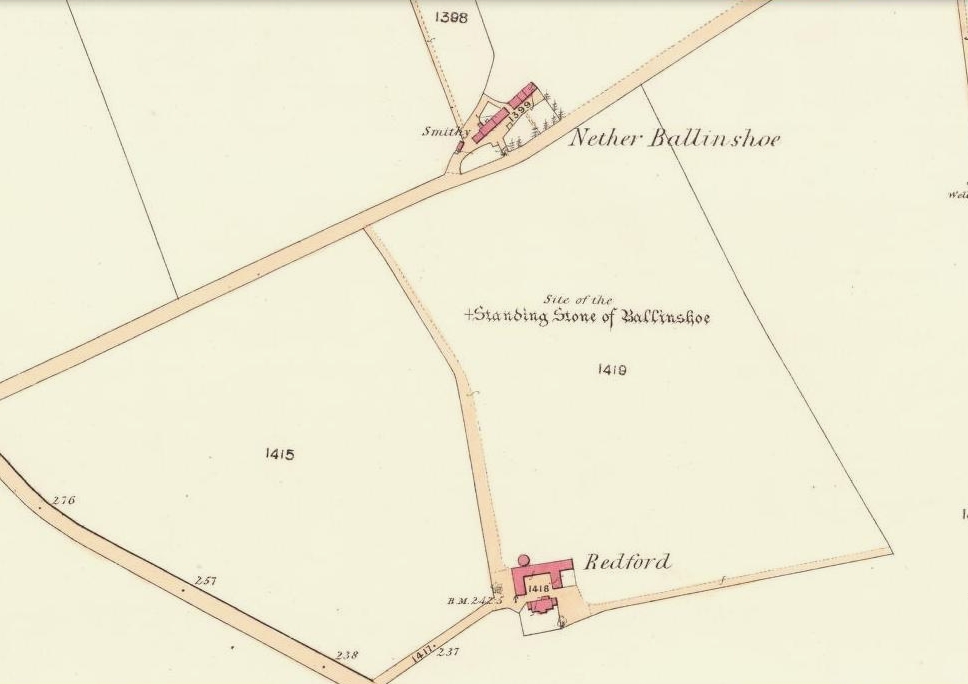

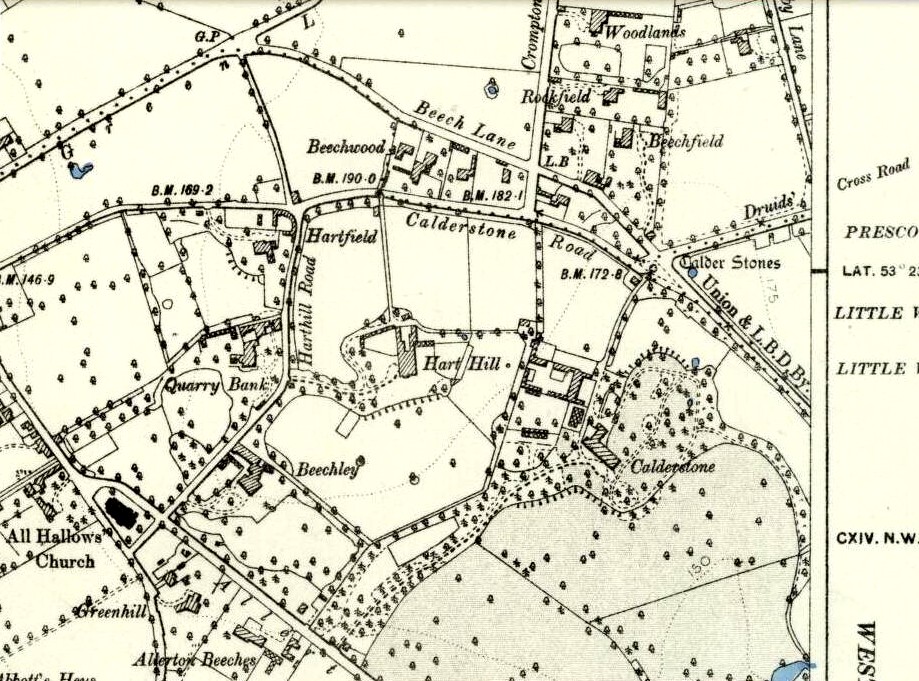

Marked on the 1846 Ordnance Survey map in a position by the road junctions at the meeting of township boundaries, where the aptly-named Calderstones Road and Druids Cross Road meet, several hundred yards north of its present site in Harthill Greenhouses in Calderstones Park, this is a completely fascinating site whose modern history is probably as much of a jigsaw puzzle as its previous 5000 years have been!

Thought to have originally have been a chambered tomb of some sort, akin to the usual fairy hill mound of earth, either surrounded by a ring of stones, or the stones were covered by earth. The earliest known literary reference to the Calderstones dates from 1568, where it is referenced in a boundary dispute, typical of the period when the land-grabbers were in full swing. The dispute was over a section of land between Allerton and Wavertree and in it the stones were called “the dojer, rojer or Caldwaye stones.” At that time it is known that the place was a roughly oval mound. But even then, we find that at least one of the stones had been taken away, in 1550.

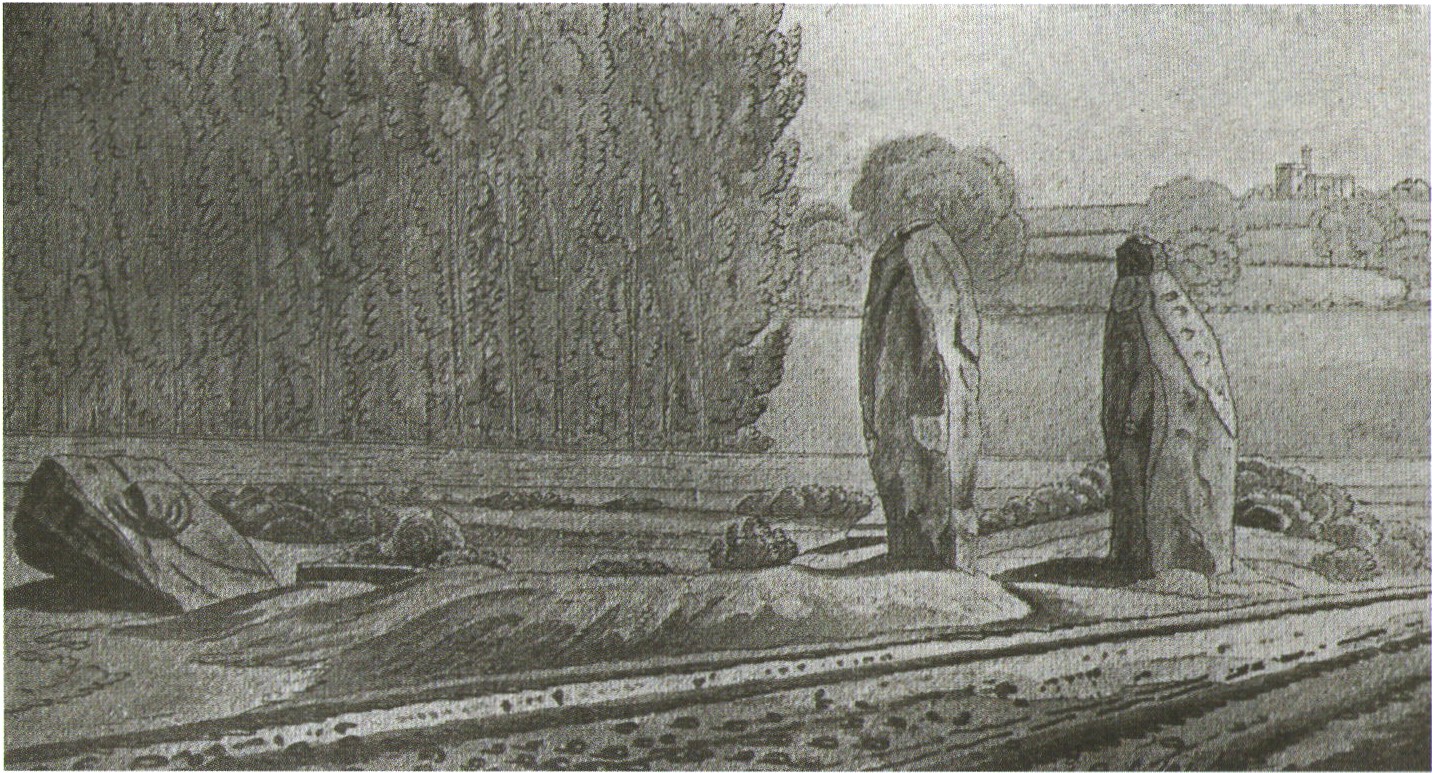

Little was written about the place from then until the early 19th century, when descriptions and drawings began emerging. The earliest image was by one Captain William Latham in 1825. On this (top-right) we have the first hint of carvings on some of the stones, particularly the upright one to the right showing some of the known cup-markings that still survive. By the year 1833 however, the ‘mound’ that either surrounded or covered the stones was destroyed. Victorian & Paul Morgan (2004) told us,

“The destruction first began in the late 18th or early 19th century when the mound was largely removed to provide sand for making mortar for a Mr Bragg’s House on Woolton Road. It was at this time that a ‘fine sepulchral urn rudely ornamented outside’ was found inside.”

The same authors narrated the account of the mound’s final destruction, as remembered by a local man called John Peers—a gardener to some dood called Edward Cox—who was there when it met its final demise. Mr Cox later wrote a letter explaining what his gardener had told him and sent it to The Daily Post in 1896, which lamented,

“When the stones were dug down to, they seemed rather tumbled about in the mound. They looked as if they had been a little hut or cellar. Below the stones was found a large quantity of burnt bones, white and in small pieces. He thought there must have been a cartload or two. He helped to wheel them out and spread them on the field. He saw no metal of any sort nor any flint implements, nor any pottery, either whole or broken; nor did he hear of any. He was quite sure the bones were in large quantity, but he saw no urn with them. Possibly the quantity was enhanced by mixture with the soil. No one made such of old things of that sort in his time, nor cared to keep them up…”

But thankfully the upright stones remained—and on them were found a most curious plethora of neolithic carvings. After the covering cairn had been moved, the six remaining stones were set into a ring and, thankfully, looked after. These stones were later removed from their original spot and, after a bit of messing about, came to reside eventually in the curious greenhouse in Calderstones Park.

The carvings on the stones were first described in detail by the pioneering James Simpson. (1865) I hope you’ll forgive me citing his full description of them—on one of which he could find no carvings at the time, but he did state that his assessment may be incomplete as the light conditions weren’t too good. Some things never change! Sir James wrote:

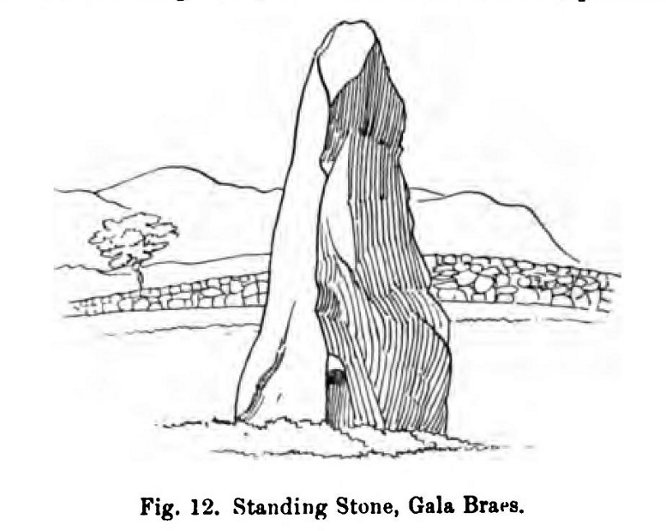

“The Calder circle is about six yards in diameter. It consists of five stones which are still upright, and one that is fallen. The stones consist of slabs and blocks of red sandstone, all different in size and shape.

“The fallen stone is small, and shews nothing on its exposed side; but possibly, if turned over, some markings might be discovered on its other surface.

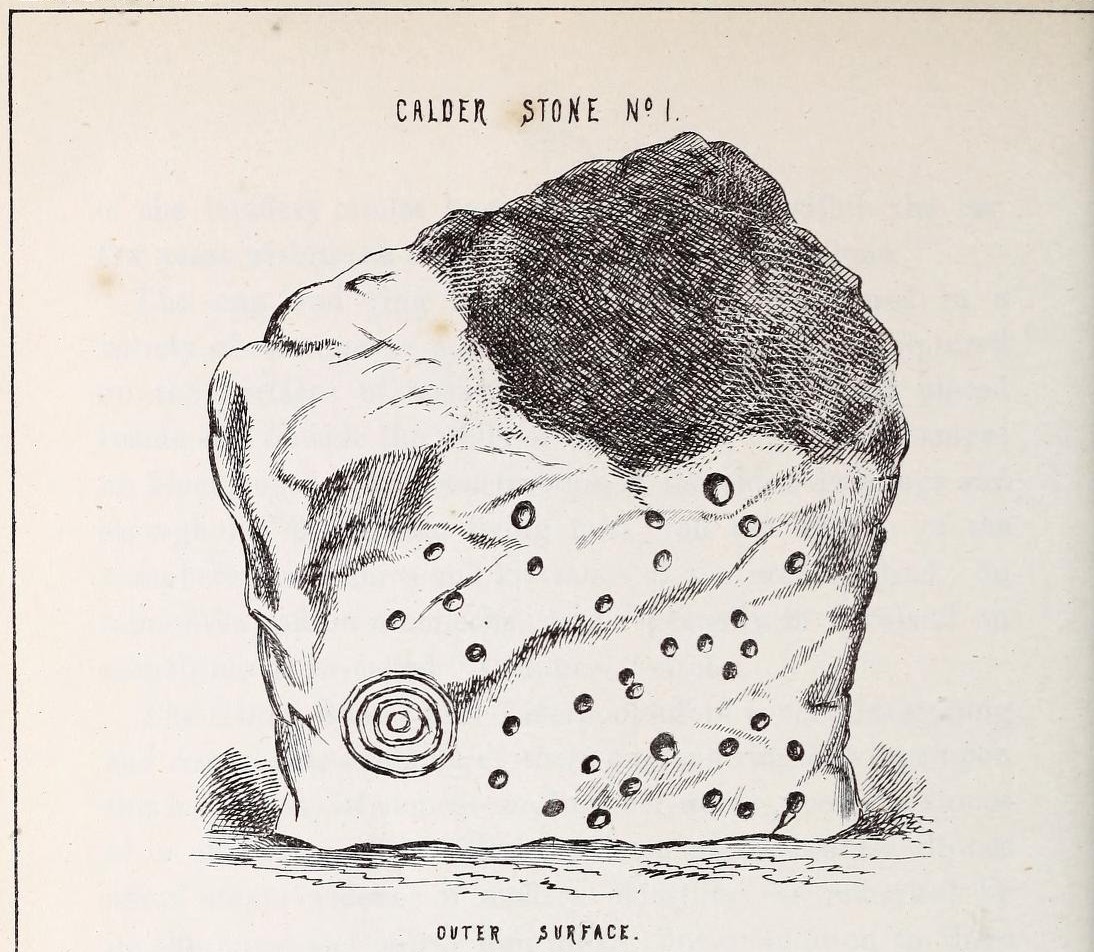

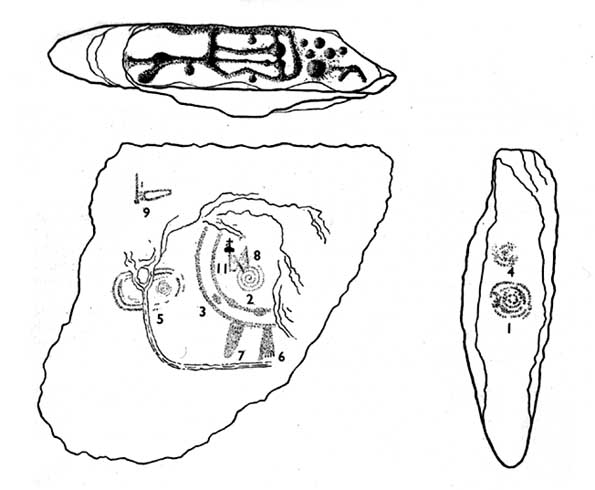

“Of the five standing stones, the largest of the set (No. I) is a sandstone slab, between five and six feet in height and in breadth. On its outer surface—or the surface turned to the exterior of the circle— there is a flaw above from disintegration and splintering of the stone; but the remaining portion of the surface presents between thirty and forty cup depressions, varying from two to three and a half inches in diameter; and at its lowest and left-hand corner is a concentric circle about a foot in diameter, consisting of four enlarging rings, but apparently without any central depression.

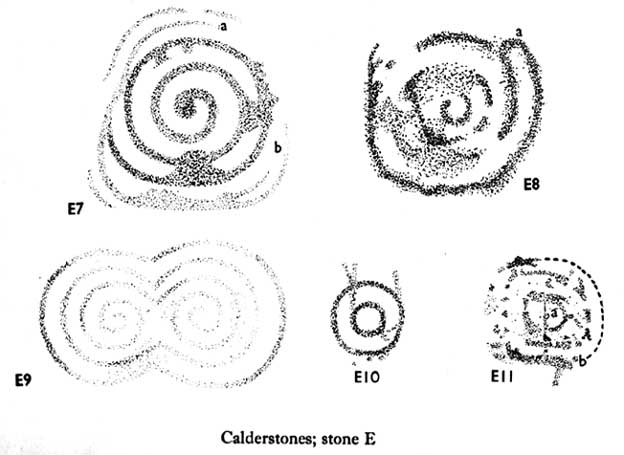

“The opposite surface of this stone, No. 1, or that directed to the interior of the circle, has near its centre a cup cut upon it, with the remains of one surrounding ring. On the right side of this single-ringed cup are the faded remains of a concentric circle of three rings. To the left of it there is another three-ringed circle, with a central depression, but the upper portions of the rings are broken off. Above it is a double-ringed cup, with this peculiarity, that the external ring is a volute leading from the central cup, and between the outer and inner ring is a fragmentary line of apparently another volute, making a double-ringed spiral which is common on some Irish stones, as on those of the great archaic mausoleum at New Grange, but extremely rare in Great Britain. At the very base of this stone, and towards the left, are two small volutes, one with a central depression or cup, the other seemingly without it. One of these small volutes consists of three turns, the other of two.

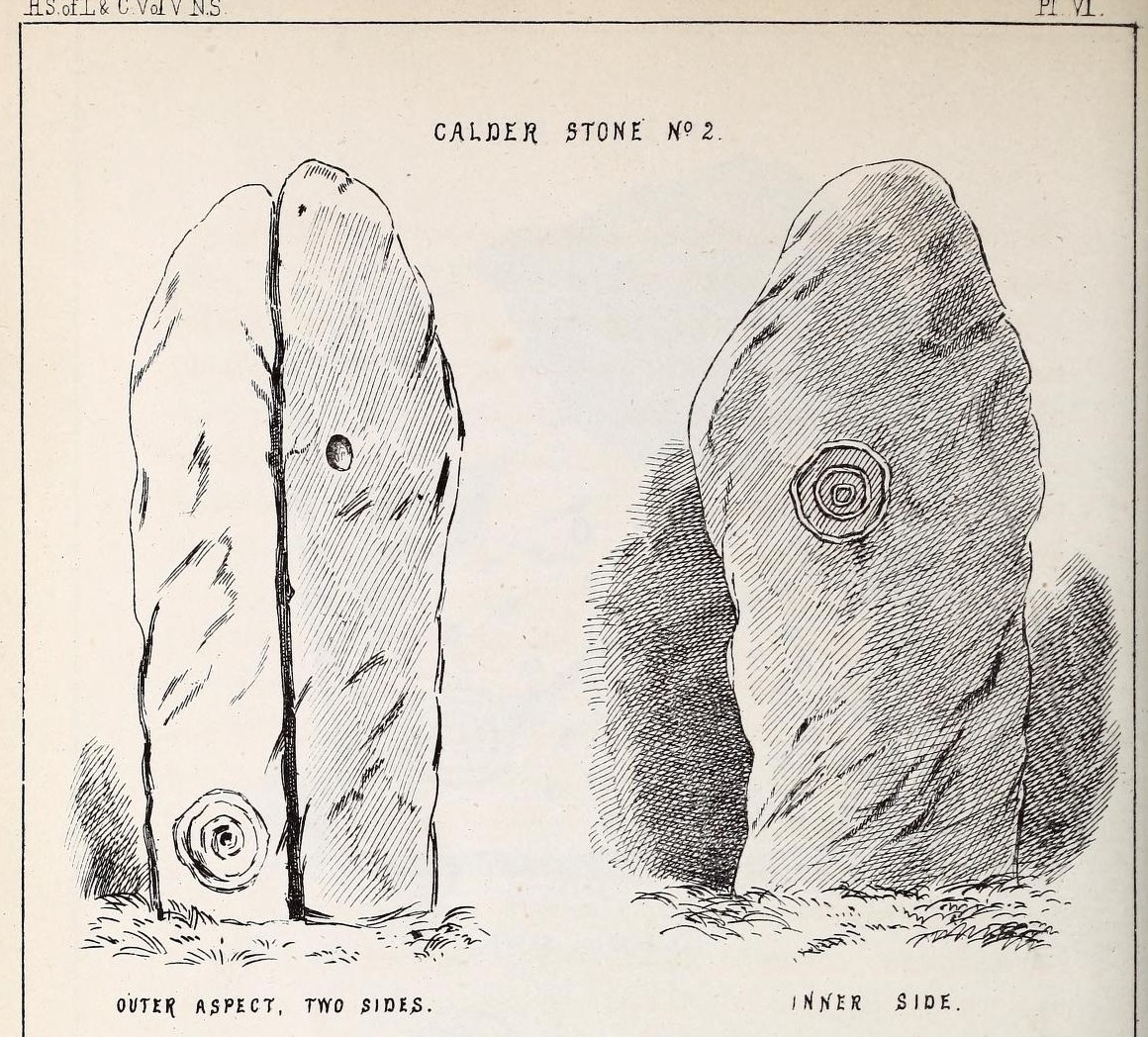

“The next stone, No. 2 in the series, is about six feet high and somewhat quadrangular. On one of its sides, half-way up, is a single cup cutting; on a second side, and near its base, a volute consisting of five rings or turns, and seven inches and a half in breadth ; and on a third side (that pointing to the interior of the circle), a concentric circle of three rings placed half-way or more up the stone.

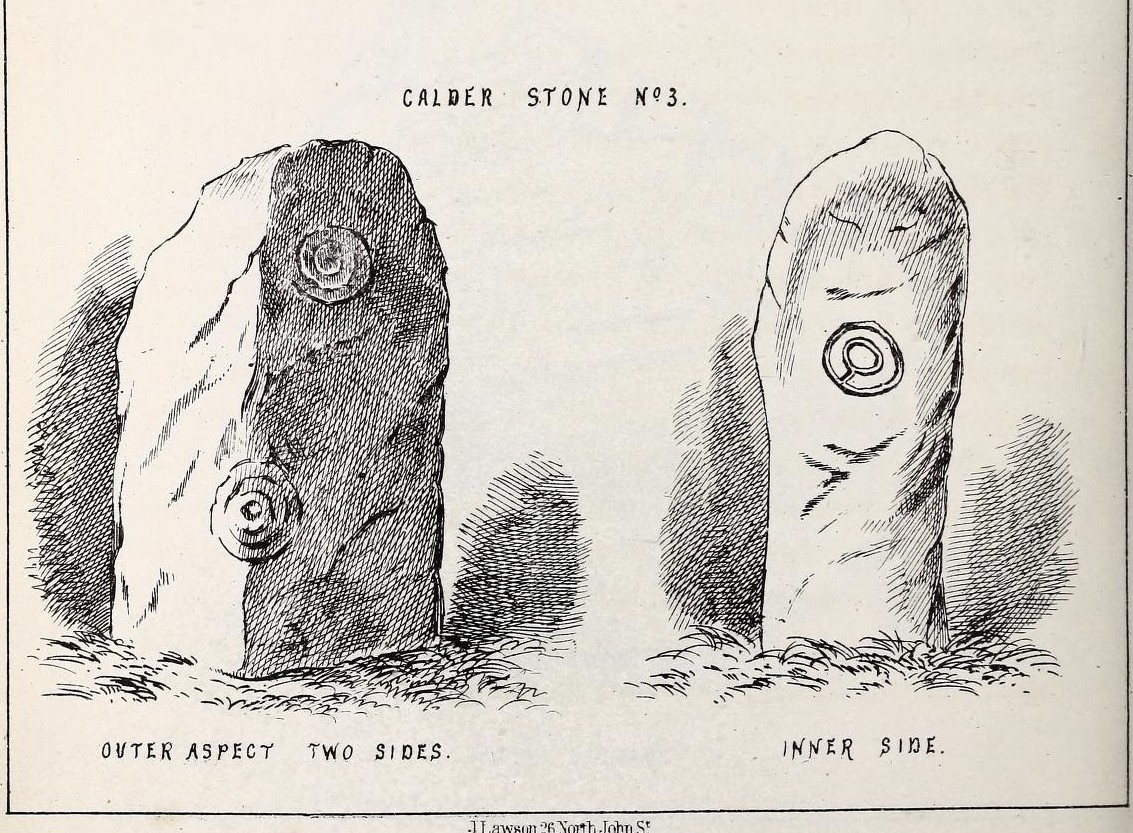

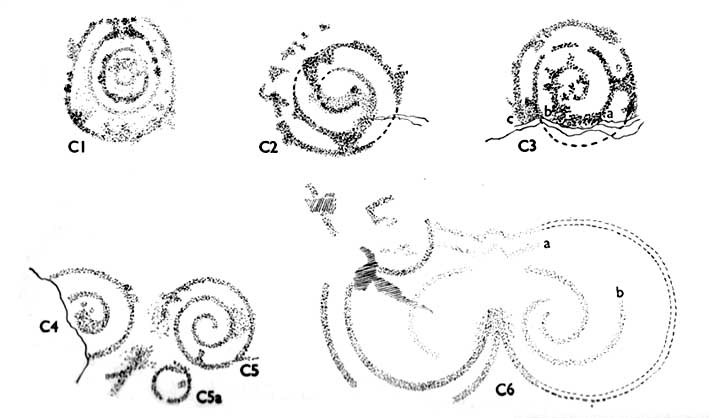

“The stone No. 3, placed next to it in the circle, is between three and four feet in height; thick and somewhat quadrangular, but with the angles much rounded off. On its outermost side is apparently a triple circle cut around a central cup; but more minute examination and fingering of the lines shews that this figure is produced by a spiral line or volute starting from the central cup, and does not consist of separate rings. The diameter of the outermost circle of the volute is nearly ten inches. Below this figure, and on the rounded edge between it and the next surface of the stone to the left, are the imperfect and faded remains of a larger quadruple circle. On one of the two remaining sides of this stone is a double concentric circle with a radial groove or gutter uniting them. This is the only instance of the radial groove which I observed on the Calder Stones, though such radial direct lines or ducts are extremely common elsewhere in the lapidary concentric circles.

“The stone No. 4 is too much weathered and disintegrated on the sides to present any distinct sculpturings. On its flat top are nine or ten cups ; one large and deep (being nearly five inches in diameter). Seven or eight of these cups are irregularly tied or connected together by linear channels or cuttings…

“The fifth stone is too much disfigured by modern apocryphal cuttings and chisellings to deserve archaeological notice.

“The day on which I visited these stones was dark and wet. On a brighter and more favourable occasion perhaps some additional markings may be discovered.”

It wasn’t long, of course, before J. Romilly Allen (1888) visited the Calderstones and examined the carvings; but unusually he gave them only scant attention and added little new information. Apart from reporting that another of the monoliths had carvings on it, amidst a seven-page article the only real thing of relevance was that,

“Five of the Calderstones show traces, more or less distinct, of this kind of carving, the outer surface of the largest stone having about thirty-six cups upon it, and a set of four concentric rings near the bottom at one corner. One of the stones has several cups and grooves on its upper surface.”

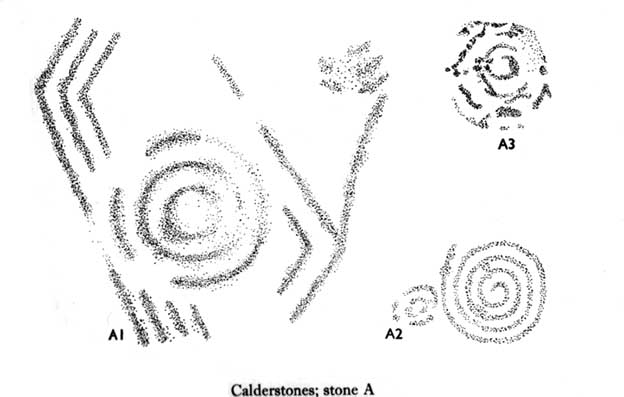

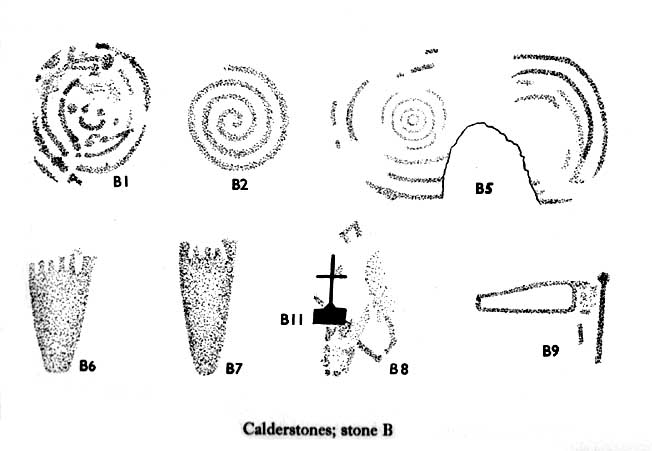

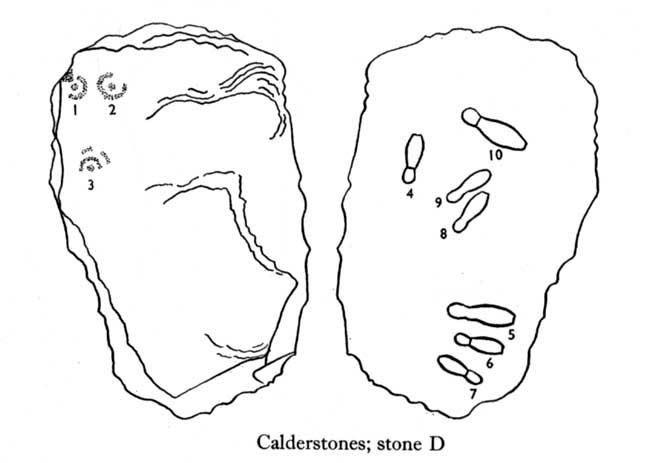

Unusual for him! The major survey of the Calderstone carvings took place in the 1950s when J.L. Forde-Johnson (1956; 1957) examined them in great detail. His findings were little short of incredible and, it has to be said, way ahead of his time (most archaeo’s of his period were simply lazy when it came to researching British petroglyphs). Not only were the early findings of Sir James Simpson confirmed, but some fascinating rare mythic symbols were uncovered that had only previously been located at Dunadd in Argyll, Cochno near Glasgow, and Priddy in Somerset: human feet – some with additional toes! Images of feet were found to be carved on Stones A, B and E. A carved element on Stone C may even represent a human figurine—rare things indeed in the British Isles!

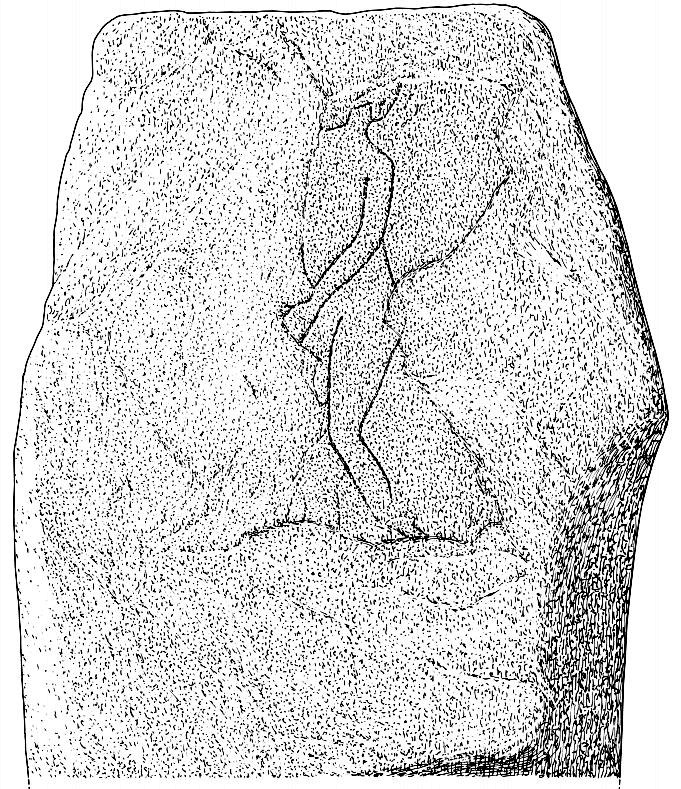

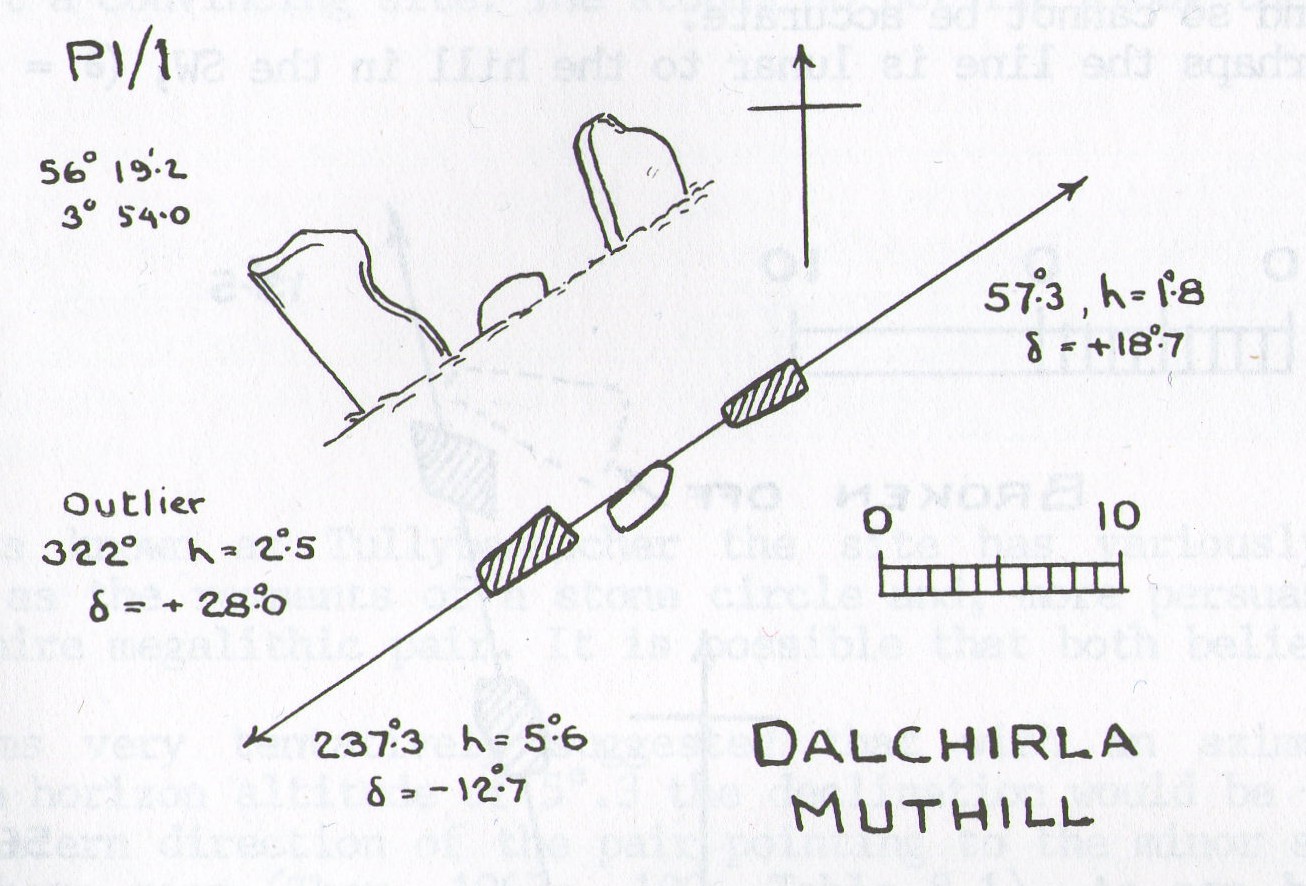

The detailed sketches here are all from Forde-Johnson’s 1957 article, where five of the six stones were found to bear petroglyphs (the sixth stone has, more recently, also been found to also possess faint carvings of a simple cup-mark and five radiating lines).

The date of the site is obviously difficult to assess with accuracy; but I think it is safe to say that the earlier archaeological assumptions of the Calderstones being Bronze Age are probably wrong, and the site is more likely to have been constructed in the neolithic period. It’s similarity in structure and form to other chambered tombs—mentioned by a number of established students from Glyn Daniel (1950) to Frances Lynch—would indicate an earlier period. The fact that no metals of any form have ever been recovered or reported in any of the early accounts add to this neolithic origin probability.

There is still a lot more to be said about this place, but time and sleep are catching me at the mo, so pray forgive my brevity on this profile, until a later date…

Folklore

Curiously, for such an impressive site with a considerable corpus of literary references behind it, folklore accounts are scant. The best that Leslie Grinsell (1976) could find in his survey was from the earlier student C.R. Hand (1912), who simply said that,

“They were looked upon with awe by the people about as having some religious significance quite beyond their comprehension.”

There is however, additional Fortean lore that has been written about these stones and its locale by John Reppion (2011).

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Calderstones, near Liverpool,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 44, 1888.

- Ashbee, Paul, The Bronze Age Round Barrow in Britain, Phoenix House: London 1960.

- Baines, Thomas, Lancashire and Cheshire, Past and Present – volume 2, William MacKenzie: London 1870.

- Beckensall, Stan, British Prehistoric Rock Art, Tempus: Stroud 1999.

- Beckensall, Stan, Circles in Stone: A British Prehistoric Mystery, Tempus: Stroud 2006.

- Cowell, Ron, The Calderstones – A Prehistoric Tomb in Liverpool, Merseyside Archaeological Trust 1984.

- Crawford, O.G.S., The Eye Goddess, Phoenix House: London 1957.

- Daniel, Glyn E., The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales, Cambridge University Press 1950.

- Faulkner, B.M., “An Analysis of Three 19th-century Pictures of the Calderstones,” in Merseyside Archaeological Journal, volume 13, 2010.

- Forde-Johnson, J.L., “The Calderstones, Liverpool,” in Powell & Daniel, Barclodiad y Gawres: The excavation of a Megalithic Chambered Tomb in Anglesey, Liverpool University Press 1956.

- Forde-Johnson, J.L., “Megalithic Art in the North West of Britain: The Calderstones, Liverpool,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 23, 1957.

- Grinsell, Leslie, Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain, David & Charles: Newton Abbot 1976.

- Hand, Charles R., The Story of the Calderstones, Hand & Co.: Liverpool 1912.

- Harrison, Henry, The Place-Names of the Liverpool District, Elliot Stock: London 1898.

- Herdman, W.A., “A Contribution to the History of the Calderstones, near Liverpool,” in Proceedings & Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society, volume 11, 1896.

- Morgan, Victoria & Paul, Prehistoric Cheshire, Landmark: Ashbourne 2004.

- Nash, George & Stanford, Adam, “Recording Images Old and New on the Calderstones in Liverpool,” in Merseyside Archaeological Journal, volume 13, 2010.

- Picton, James A., Memorials of Liverpool – 2 volumes, Longmans Gree: London 1875.

- Reppion, John, “The Calderstones of Liverpool,” in Darklore, volume 6, 2011.

- Roberts, D.J., “A Discussion Regarding the Prehistoric Origins of Calderstones Park,” in Merseyside Archaeological Journal, volume 13, 2010.

- Simpson, J.Y., “On the cup-cuttings and ring cuttings on the Calderstones, near Liverpool,” in Proceedings of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, volume 17, New Series 5, 1865.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Taylor, Isaac, Words and Places, MacMillam: London 1885.

- Stewart-Brown, Ronald, A History of the Manor and Township of Allerton, Liverpool 1911.

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to the staff at Calderstones Park; thanks also to the very helpful staff at Liverpool Central Library.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian