Hillfort: OS Grid Reference – C 36686 19721

Also Known as:

- Grianan Ailighe

- Grianan of Ailech

- National Monument 140

Archaeology & History

Attributed by Michael Dames (1996) and others before him as the abode of the Dagda and the house of the sun, this huge monument was recorded in the Irish Annals as being destroyed in 1101 AD following a great battle. A site of mythic importance to the very early Irish Kings and Queens, and used by the shamans of the tribes, The Grianan is a place of of legendary importance to folklorists, historians and archaeologists alike and has been widely described over the last 150 years. Although the site you see today was hugely reconstructed between the years 1874 and 1878, it’s still impressive and, wrote George Petrie (1840), commands,

“one of the most extensive and beautifully varied panoramic prospects to be found in Ireland”!

Used over very long periods of time, the archaeologist Brian Lacy (1983) described the Grianan, on the whole, as,

“a restored ‘cashel’*, centrally placed within a series of three enclosing earthen banks; the site of an approaching ‘ancient road’; and a holy well.”

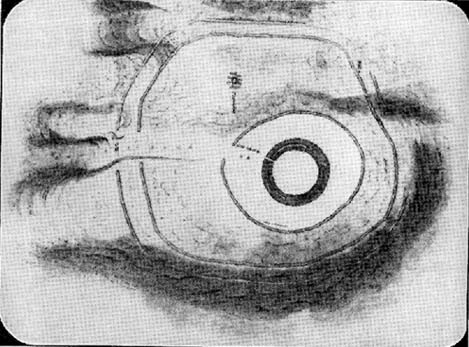

Lacy’s description in the Donegal Inventory is considerable and culls from the various surveys and reports done in the past. First surveyed by George Petrie in 1835, the internal body of the stone-built site is roughly circular and measures around 25 yards across, with a singular entrance on its eastern (sunrise) side. A stone ‘seat’ is at the end of the internal passage. At the centre of the huge ‘room’, Petrie recorded traces of a rectangular stone structure that he thought might have been the remnants of some old chapel built sometime in the 18th century.

More than 25 yards outside of the primary stone building is another surrounding embankment, oval in shape, low to the ground and with another singular entrance to the east — though this entrance is not in line with that of the main structure. At a further distance out from this embankment are the remains of another two oval ‘enclosures’, though the the remains of the outermost one is considerably more fragmented.

Although the replenished ‘fort’ dates from the Iron Age, early remains here are thought to have been of Bronze Age origin. A ‘tumulus’, now gone, being one such find here.

Folklore

There is much legend here. The creation myth narrated by Scott (1938) tells that it was,

“built originally by the Daghda, the celebrated king of the Tuatha de Danann, who planned and fought the battle of the second or northern Magh Tuireadh against the Formorians. The fort was erected around the grave of his son Aeah (or Hugh) who had been killed through jealousy by Corgenn, a Connacht chieftain.”

From similar legendary sources, it is told that,

“the time to which the first building of Aileach may be referred, according to the chronology of the Four Masters, would be about seventeen hundred years before the christian era. There are strong grounds for believing that the Grianan as a ‘royal’ seat was known to Ptolemy, the Greek geographer, who wrote in AD 120. In his map of Ireland he marks a place, Regia…which corresponds fairly well with its situation.”

By the outer banking on the south-side of the fortress is the remains of a much-denuded spring of water, the old water supply for this place. It gained the reputation of being a holy well, dedicated to St. Patrick.

…the be continued…

References:

- Dames, Michael, Mythic Ireland, Thames & Hudson: London 1996.

- Harbison, Peter, Guide to the National Monuments in the Republic of Ireland, Gill & MacMillan: Dublin 1982.

- Lacy, Brian, Archaeological Survey of County Donegal, DCC: Lifford 1983.

- Petrie, George, ‘The Castle of Donegal,’ in Irish Penny Journal, 1, 1840.

- Scott, Samuel, ‘Grianan of Aileach,’ in H.P. Swan’s Book of Inishowen, Buncrana 1938.

- Swan, Harry Percival, The Book of Inishowen, William Doherty: Buncrana 1938.

Links:

- Guarding the Grianan – the WordPress Word

- Grianan of Aileagh – Stone House of the Sun

* Cashels are “monuments similar in type to earthen ringforts, but enclosed by walls of drystone construction.”

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian