‘Stone Circle’: OS Grid Reference – NN 838 032

Archaeology & History

An intriguing entry inasmuch as we don’t know the full history and nature of the site. Whether this site was the “druidical circle” mentioned in the 1791 Old Statistical Account of Scotland ” upon the heights of Sheriffmuir,”(vol.3, p.210), we cannot be sure. The site was certainly described by Mr Hutchinson (1893) more than a century ago as a “stone circle”, but earlier still in a short piece in the Stirling Journal of May 5, 1830. It read:

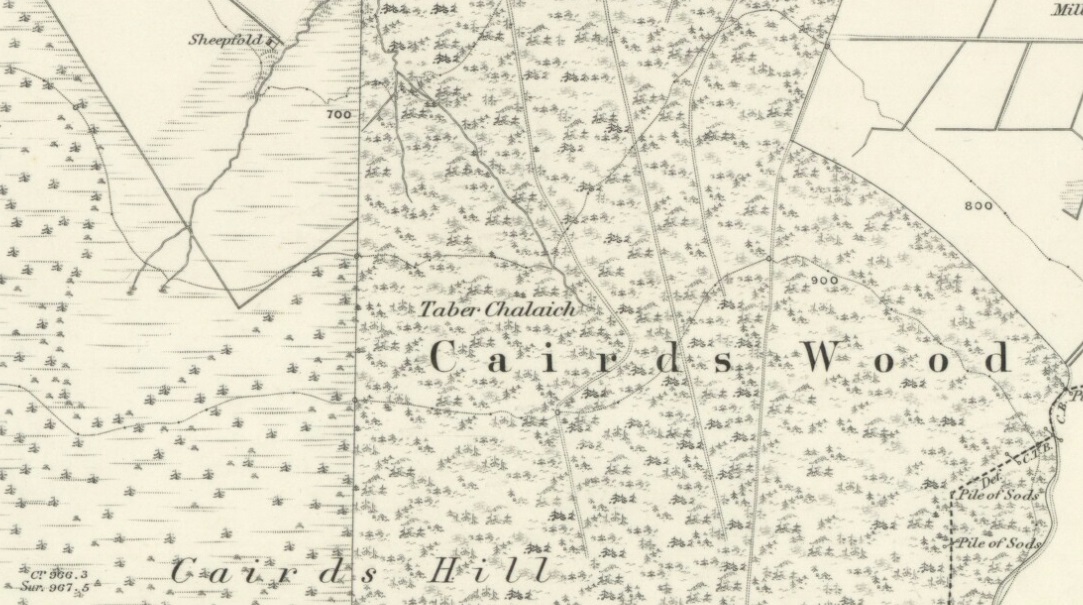

“About eight miles from Stirling by the Sheriffmuir Road, near a place called Harperstone, there is a remarkable circle of stones, supposed to have been a druidical place of worship of old. The site of this circle is rather uncommon in this country — being on the back summit of a high hill, one of the Ochils called the Black Hill, and exposed to every wind that blows. It is about two english miles south of the present roadway.”

The writer’s notes then told of some curious finds by this circle, giving the impression that it may have had another function: perhaps a cairn of sorts; perhaps an ancient building — we may never know. Nevertheless, his information is intriguing.

“Tradition records two remarkable circumstances connected with this druidical circle, which may perhaps be worthy of being preserved. About the middle of last century (c.1750) there were dug up at the foot of the larger stones three vessels of clay of antique shapes, containing coins of very ancient date, which were long preserved by Monteath of Park, but are now, we regret to say, lost. So late as 1770, these coins were, it is said, to be seen at Park House, all of gold. About the year 1715, some stones on which had been engraved inscriptions were dug up at the same place; and at a previous period specimens of ancient Pictish armour were dug up from the bowels of this hill, which had been carefully deposited of yore some feet below the surface in crypts of curious description.”

When Mr Hutchinson came to explore this region in search of the stone circle, his nose took him to a site a few hundred yards north of nearby Harperstone Farm, where he found a large stone:

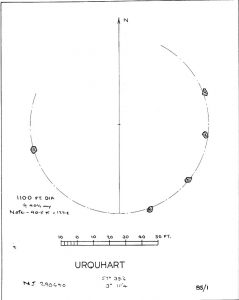

“It is 9 feet long by 6 feet across on the top, is 3 feet thick and measures 26 feet round. This appears to have been a centre stone, and a surrounding circle is traceable more or less distinctly — moreso to the west and north, less so to the east and south. The radius of the circle is about 15 yard, and a similar distance separates each of the larger stones yet traceable in the circle. The ground beside the great central stone appears to have been excavated…”

But it would seem that Hutchinson’s site and the one described in the Stirling Journal of 1830 are two distinctly separate items if their relative topographical descriptions are to be accepted. No doubt — like many a-local who’s found these same written accounts — when we visited and wandered back and forth over the Black Hill site in Autumn 2010, we were as puzzled as others before us in finding nothing on the named Black Hill. Nothing that could remotely be viewed as the circle described was anywhere in evidence. The only thing that we found of any potential was on the flat below the southern ridge of the hill, heading towards the small copse of trees, where is a possible ring of seven stones, albeit a low one, in an ellipse formation. The ground was much overgrown and a spring of water emerged from the edge of where might have been an eighth stone. The photo shown here was the best we could get of the site. It’s unlikely to be the place which Messrs Hutchinson and company wrote about.

A more detailed examination of the landscape around this ‘Harperstone Circle’ is needed.

References:

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones of Stirling District,” in The Stirling Antiquary, volume 1, 1893.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian