Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 81382 99686

Nearly 600 yards west of the old Sheriffmuir Road (between Bridge of Allan to Greenloaning), you’re best approaching it up the zigzaggy lane from above Stirling Uni until it levels out beyond the main wooded area where the hills open up on either side of you. There’s a little touristy parking spot further along the road, just below a small wooded bit. Go past this and look out for the small peaked hill nearly a half-mile NW on your left. Take whichever footpath you fancy (if you see one) and get to the top of that hill!

Archaeology & History

This is a wonderful spot, located at the highest point on this small moorland region on the western edge of the Ochil Hills. I haven’t found too much written about this once proud, but now fallen monolith — which seems unusual considering its size, cos it’s huge! It would have stood out and been visible for miles around. Quite when it was felled, I cannot find. The only info I’ve got here (Royal Commission 1963) tells:

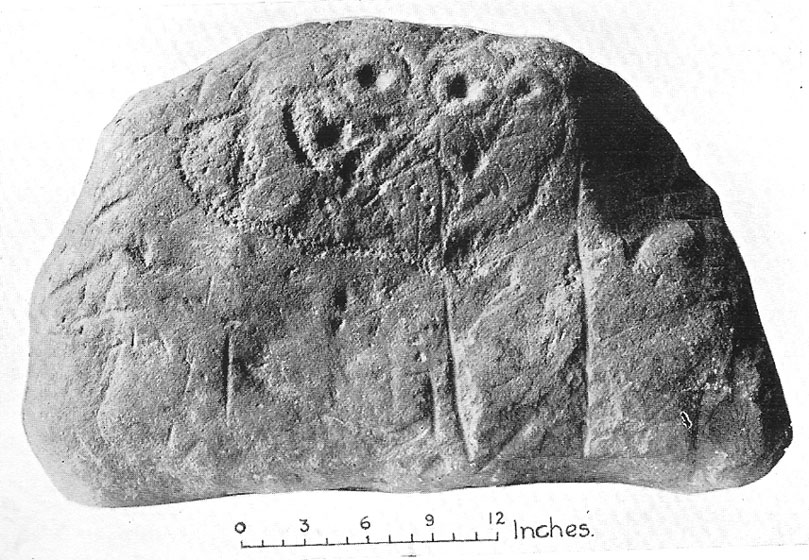

“Lying recumbent on a grassy patch among the heather, it is a four-sided pillar measuring 13ft in length, a maximum of 4ft 6in across the wider side, and a maximum of 1ft 6in across the narrower side.”

In enquiring about the nature of this stone a few years ago, a local chap who called himself ‘Wharryburn’ wrote to say, “I believe the laid-out stone is a fallen standing stone. My grandfather was gamekeeper at Airthrey Estate and responsible for the shooting on the moor there he passed it to my father etc… It’s the local volcanic stone, not an ice-dropped erratic. There are also a few biggish stones at points around that I tried to make some sense out of a few years ago, but no luck.”

The great hill of Dumyat rises to its east; a short distance north is a megalithic stone row with its upright Wallace Stone; whilst the overgrown prehistoric cairns of Pendreich 1, 2 and 3 live on the small hillocks a few hundred yards to the south.

References:

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian