Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 8551 8819

Archaeology & History

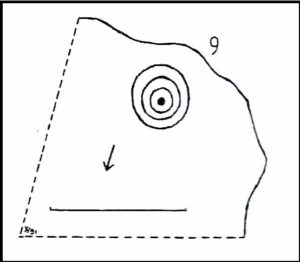

Near the northwestern end of the small geological ridge that runs to the west of Castleton farmhouse, close to an awesome nine-ringed carving, we find this more simplified triple-ringed petroglyph. And although the carving is easy enough to describe, its labelling (as ‘Castleton 7c’) is rather troublesome. As with other carvings in this locale, the name of the stone is based on a survey done by Maarten van Hoek in the mid-1990s. But van Hoek’s sketch of Castleton 7c and the one shown in our photos, whilst very similar, possess attributes that aren’t on van Hoek’s drawing. Now this isn’t too odd, as many petroglyphs look different when lighting conditions change; to the point where some features you can see one day are almost invisible the next. But this carving has attributes that are very difficult to miss – and van Hoek’s detailing tended to be good. But, all this aside: until we can verify with certainty one way or the other and despite my suspicions that this isn’t what van Hoek described, I’m still entering this carving as Castleton 7c. So – now that bit’s out of the way…!

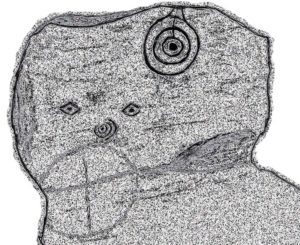

When we visited the site two years ago the day was dark and overcast, so we didn’t really have good conditions for seeing any faint carvings. But this wasn’t faint, thankfully. It was completely buried beneath soil and gorse bushes, but thankfully Paul Hornby managed to unearth the one you can see in the photos. If it is the Castleton 7c petroglyph, it was rediscovered by van Hoek on one of his ventures here in 1985.

When we visited the site we only managed to uncover a small section of the stone, as the roots of the surrounding gorse prevented us from seeing more. (it’s tough stuff unless you’ve got the right gardening equipment!) The section we uncovered consisted of a cup-and-triple-ring. This is consistent with van Hoek’s sketch and description; but we also found there were two very notable ‘arcs’ on the outer edge of the rings—nearly opposite each other—as if another, fourth ring had been started. You can’t really miss these elements – and even in the poor lighting conditions we had, these outer arcs are very evident on a number of photos – especially when they are expanded to full-scale. However, as I mentioned, we were unable to uncover all the rock; but when van Hoek was here there was far less herbage. What he saw on this carving was as follows:

“Deturfing part of this ridge revealed a fine cup with three rings with a broadly pecked tail; one solo cup; one large oval ring with small central cup; and a faint cup with two rings, the outer one incomplete. The rock slopes 12º ENE.”

The “broadly pecked tail” he mentions is also not really clear in any of the 60 photos we took. There is a faint line that runs through the three rings, into the central cup and out the other side: a single curving line no less. It’s certainly visible, but it’s far from broad. But there are a number of other lines coming out of the rings. These maybe just natural scratch marks, or even scratches acquired from farming activity. It’s difficult to say. In the poor light that we had, there as looked to be a single cupmark a few inches away from the rings, but this isn’t consistent with the position of the cupmark on van Hoek’s sketch.

There’s a simple solution to all this: we need to revisit the site and expose more of the rock. At least that will tell us once and for all whether this is the same as van Hoek’s stone, or whether we’ve found yet another new carving. Watch this space, as they say! 😉

References:

- van Hoek, Martin A.M., “Prehistoric Rock Art around Castleton Farm, Airth, Central Scotland,” in Forth Naturalist & Historian, volume 19, 1996.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian