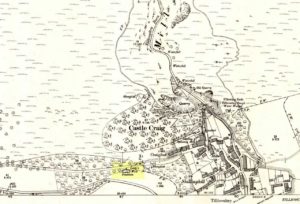

Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – SJ 898 555

If you park in the first car park at Greenaway Country Park past the lake, and then walk along the road taking the footpath on the left around the lake, continue until one crosses a bridge, just below the Warden’s Tower taking a path which follows a small stream, past a pond and then continue until there is a bridge on the left. Just after this is a path on the right you will reach the Gawton Well.

Archaeology & History

The spring, voted one of the most mystical places and certainly one of the most atmospheric of Staffordshire’s ancient wells, is found on the remains of the Kynpersley Estate. It fills at first an elliptical stone basin, then a small rectangular basin and then a larger one which could have formed a bath. There is a semi-circular stone just after this and it then flows through a number of large rocks forming a stream. The site has an excellent arrangement: the juxtaposition between the man-made and the natural.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.

Folklore

This suggestion of the site being a folly may be justified by the presence of Gawton’s Stone. This is just up from the spring, being a large stone supported by three other stones. Some antiquarians identified erroneously this as either a druidic altar or megalithic structure (it would be impossible to lift the structure). However it is here that legendarily a hermit lived called Gawton who used the well. Often landowners would employ a hermit to add some romance to the estate, although the stone does not particularly look like a comfortable place. Certainly local tradition states that the man came from Knypersley Hall in the seventeenth century, although the house is 18th century and no name is recorded as living there of any note! The house itself dates from the 12th century. Robert Plot (1686) in his work on Staffordshire states that:

“There are many waters such as the water of the well at Gawton Stone…which has some reputation for the cure of the King’s evil..”

The King’s evil was a skin complaint generally called scrofula which was only thought to be cured by the touch of the reigning monarch. Now rarely do I try out springs, but at this time my little boy was suffering with eczema and having tried all sorts of creams I said flippantly try some of the well’s water. I collected it from near the source in a drinking bottle, it felt unusually silky to the skin, and applied some to an area of dry peeling skin on his cheek. Remarkably by the time we had walked from the well to the car the area have healed itself rather miraculously. I only wished I had collected some more to use later, although the area on his face disappeared for good….

In all Gawton’s Well deserves to be more well known, a magical site of which my only clue, many years ago before the internet, to its existence before reaching it was a circle on the OS-map! A site which may reveal its secrets with greater research, which I plan to undertake whilst preparing for the Staffordshire book below.

References:

- Parish, R.B., Holy wells and healing springs of Staffordshire (forthcoming) full set of references within.

- Plot, Robert, A Natural History of Staffordshire, Oxford 1686.

Links:

© R.B. Parish, The Northern Antiquarian