Cup-and-Ring Stone (lost): OS Grid Reference – NX 68700 44699

Archaeology & History

This impressive-looking carving was rediscovered in the 1880s during one of Fred Coles’ ventures uncovering many of the petroglyphs in this area. It could be found, he said, “some three hundred yards south-east of Balmae House.” When the local historian Malcolm Harper visited Samuel Fletcher who lived in the cottage at Balmae a few years after it had been discovered, he spoke enthusiastically about the carvings and knew much about them, but Harper doesn’t specifically mention whether or not he’d seen this stone (he probably did). Nowadays the carving is covered in thickets of gorse and and, as a result, it hasn’t been seen in many a year. The great Scottish petroglyph hunter Kaledon Naddair may have been one of the last people to visit it.

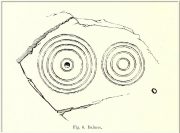

It’s impressive, as Mr Coles’ (1895) sketch shows, comprising, as he said, of

“two sets of concentric rings, one having four, the other five and a central cup. It is smooth, and slopes to the W. at an angle of 40°. The largest ring is 24 inches in diameter.”

A number of other impressive multiple-ringed carvings exist hereby that have also fallen prey to the cover of gorse. So get some hedge-cutters and decent gardening gloves if you’re gonna look for this one!

References:

- Coles, Fred, “A Record of the Cup-and-Ring Markings in the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 29, 1895.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of South-West Scotland,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 14, 1967.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Galloway and the Isle of Man, Blandford: Poole 1979.

- Morris, Ronald W.B. & Bailey, Douglas C., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of Southwestern Scotland: A Survey,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 98, 1967.

- Royal Commission Ancient & Historical Monuments & Constructions of Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in Galloway – volume 2: County of the Stewatry of Kirkcudbrightshire , HMSO: Edinburgh 1914.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian