Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 81410 96489

Also Known as:

- Airthrey Castle Stone

- Canmore ID 47115

- Stirling University Stone

Dead easy to find! From Stirling head out on the A9 road towards Bridge of Allan and Stirling Uni. You’ll hit a small roundabout a mile out of Stirling – go straight across and up the little bendy road. Follow this round the bottom side of the Uni for a half-mile, watching out for the left-turn as the tree-line ends, taking you up to the factory behind the trees (if you hit the roundabout a bit further on, you’ve gone too far!). Go up the slope and onto the level sports playing fields – where this old beauty will catch your eye! If you somehow miss it, just get to the Uni and ask some of the students where it is!

Archaeology & History

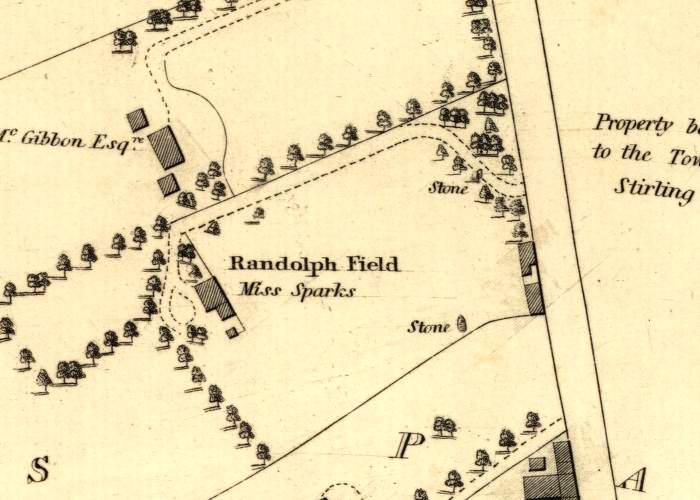

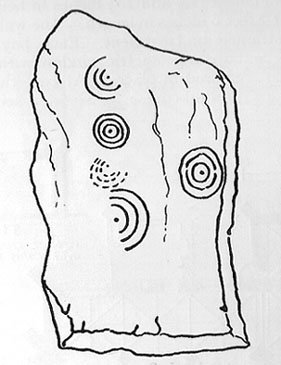

This single standing stone is a beauty! It’s big – it’s hard – and it’s bound to get you going! (assuming you’re into megaliths that is) Standing proud and upright on the eastern fields of the Stirling University campus, A.F. Hutchinson (1893) measured it as being “9ft 1in in height. Its greatest breadth is 4ft 10in, and its circumference 14ft.” A bittova big lad! More than fifty years later when the Royal Commission (1963) lads got round to measuring its vital statistics, only an inch of the upright had been eaten by the ground. The stone was highlighted on the earliest OS-maps of the area.

Folklore

Of the potential folklore here, most pens and voices seem quiet; although Mr Hutchinson (1897) told of William Nimmo’s early thoughts, linking the history of this stone with the others nearby, saying:

“Of what events these stones are monuments can not with certainty be determined. In the ninth century, Kenneth II, assembled the Scottish army in the neighbourhood of Stirling, in order to avenge the death of Alpin his father, taken prisoner and murdered by the Picts. Before they had time to march from the place of rendezvous, they were attacked by the Picts… As the castle and town of Stirling were at that date in the hands of the Picts, the rendezvous of Kenneth’s army and the battle must have been on the north side of the river; and as every circumstance of that action leads us to conclude that it happened near the spot where these stones stand, we are strongly inclined to consider them as monuments of it. The conjecture, too, is further confirmed from a tract of ground in the neighbourhood which, from time immemorial, hath gone by the name of Cambuskenneth: that is, the field or creek of Kenneth.”

And although this hypothesis is somewhat improbable, it was reiterated in the new Statistical Account of 1845, which also suggested that this and the other Pathfoot Stone were “intended probably to commemorate some battle or event long since forgotten.”

References:

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones of Stirling District,” in The Stirling Antiquary, volume 1, 1893.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian