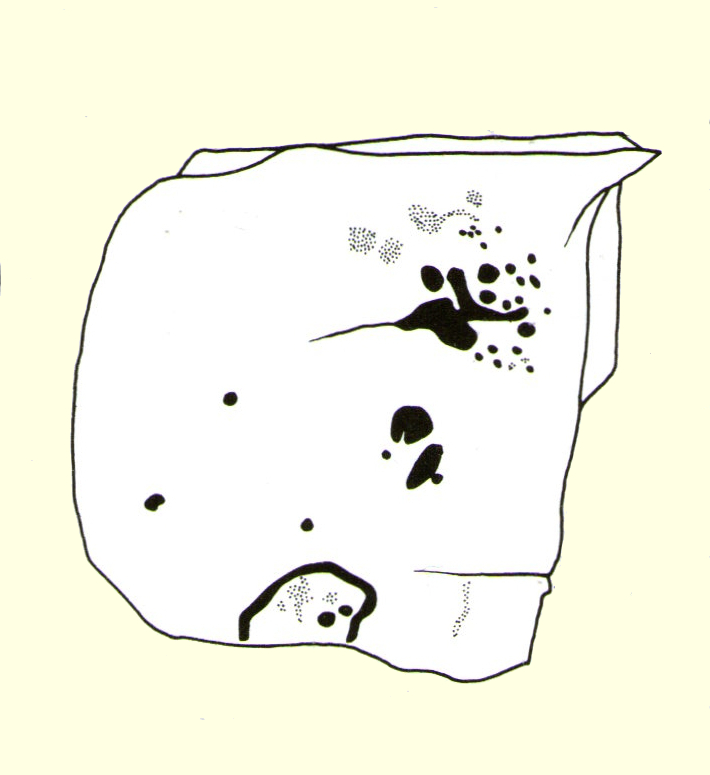

Cup-Marked Stone (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NN 5456 2084

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 24150

- Stone of the Eyes

Archaeology & History

Apparently destroyed, although some remains of the stone were said to be seen in the walling by the roadside; but when visiting this spot a few days ago the summer vegetation had completely covered any potential finds here. The stone fell foul of the usual self-righteous industrialists when the track alongside which it had sat for countless centuries was turned into a road and the stone was “blasted”. It was found some 20 yards below the large cup-marked stone known as Wester Auchleskine, seen amidst the clump of rocks in the field above.

The stone was described in MacKinlay’s (1893) fine survey on Scottish holy wells due to the healing properties of the waters that collected into the rock basin here. The earliest record of the site that I’ve found comes from the hallowed papers of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries, where—in J.M. Gow’s (1887) rambles just east of Balquidder—he told us the following:

“Going still further east to the first turning of the road beyond the farmhouse of Wester Auchleskine, and on the left-hand side, there used to be a large boulder with a natural cavity in its side, famous as a curing well for sore eyes. This stone was called “Clach nan sul” (the Stone of the Eyes). In 1878 the road trustees caused it to be blasted, as it was supposed to be a danger in the dark to passing vehicles. Its fragments were broken up, and used as road metal.”

Whether or not the site known as the Priest’s Basin, or Basan an Sagairt—a couple of hundred yards west by the roadside—was of a similar nature, or an attempt by christians to draw people away from the old healing Clach nan Sul and use this other one instead, we do not know. There are numerous accounts of other stones in this mountainous region of Scotland where rocks-with-hollows filled with water were attributed with healing properties, like the Whooping Cough Stone at Struan, the Measles Stone at Fearnan, and many others.

Folklore

The folklore described by Mr Gow was reiterated in MacKinlay’s (1893) survey. He also told how,

“The hollow in the Clach-nan-Sul at Balquhidder…contained small coins placed there by those who sought a cure for their sore eyes. Mr J. Macintosh Gow was told by some one in the district that ‘people, when going to church, having forgotten their small change, used in passing to put their hands in the well and find a coin.’ Mr Gow’s informant mentioned that he had done so himself.”

References:

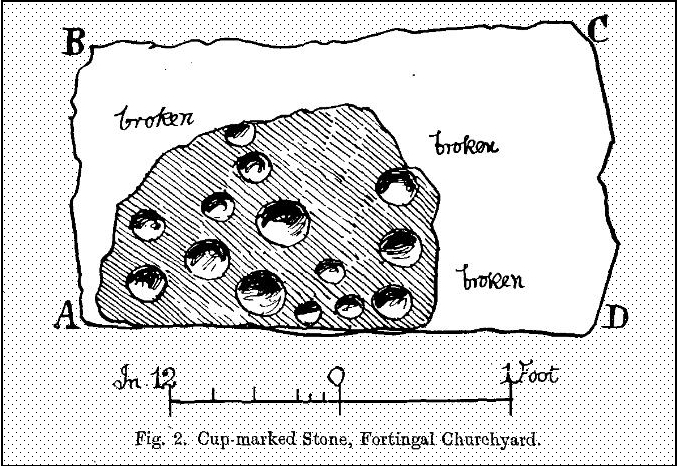

- Gow, James M., “Notes in Balquhidder: Saint Angus, Curing Wells, Cup-Marked Stones, etc”, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 21, 1887.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian