Stone Circle: OS Grid Reference – NN 863 061

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 25219

- Seven Stanes

Getting Here

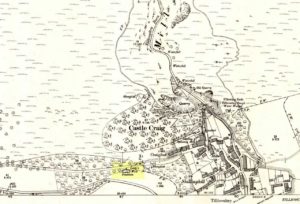

From Dunblane, head out east up and along Glen Road up towards Sheriffmuir. Turn left at the junction of the Sheriffmuir Inn and keep going for about 3 miles, keeping your eyes peeled for the TV mast on the left-hand side of the road. 100 yards past this, you can park-up. Walk down the road another 100 yards until you get to the next gate in the fence. According to Ordnance Survey, the circle is/was across the road from here.

Archaeology & History

Although local tradition and historical accounts tells of a circle of seven stones nearby, there’s little to be seen at the position shown on the OS-map. On one side of the road, just above the embankment, there are hardly any rocks at all to even remotely ascribe as being touched by humans – i.e., there’s nowt there! On the other side of the road, close to the parking spot, we do find a small cluster of rocks, perhaps hinting at a cairn structure, and then another longer stone embedded in the embankment 20 yards further down – but even these ‘remains’ (if you could call them that) seem flimsy evidence indeed of any megalithic structure here. There is also a small arc of small stones by the roadside in the same area — but even these would be stretching imagination into psilocybe realms to call them a stone circle! So I’m not sure what’s happened here. My gut feeling told me that the position of this ‘stone circle’ shown on the OS-map was wrong, but that some remains of it would be found nearby. But that could be bullshit.

Nevertheless, there are what seems to be the remains of prehistoric walling and possible enclosures close by, so a greater examination and bimble in the heathlands here is on the cards in the coming weeks. If anyone living close by has further information on this spot, or fancies walking back-and-forth through the boggy moors (it’s arduous and not for the faint-hearted) in search of such sites, lemme know! I have the feeling that there’s more to be found along this stretch of countryside.

Whether this site was the “druidical circle” mentioned in the Old Statistical Account of Scotland “in the heights of Sheriffmuir,”(vol.3, p.210), or the lost Harperstone Circle, we cannot be sure. But an early account of this lost circle was written in John Monteath’s (1885) collection of Dunblane folktales. He told:

“About two miles south-west of the village of Blackford, on the Sheriff-muir road, and near to the farm-house of Easter-Biggs, is an arch of stones, seven in number, called the “Seven Stanes,” varying from perhaps a ton to two tons each. One of these is of a round prismatical shape, and stands in an erect position. Beside these lies a large bullet of stone, called “Wallace’s Puttin’ Stane,” and he is accounted a strong man who can lift it in his arms to the top of the standing one, which is about four feet high, – and a very strong man who is able to toss it over without coming in contact with the upright one. At one time few were to be found of such muscular strength as to accomplish this – not so much from the actual weight of the stone itself, as from the difficulty of retaining hold of it, it being very smooth and circular. This difficulty, however, was obviated about seventy years ago, by the barbarous hand of a mason, to enable himself to perform the feat, since which time a person of ordinary strength can easily lift it…”

It would seem there are or were additional prehistoric sites scattering the eastern edges of the Ochils within a few miles of each other along this ridge, as several accounts from both local newspapers and learned journals talk of a number of places, of differing dimensions. The lost Harperstone Circle is a case in point; and another ‘circle’ mentioned by A.F. Hutchison in 1890, measuring just “10 – 12ft in diameter, of 5 or 6 stones, each about 2ft high” (probably a small cairn circle) differs from Monteath’s description on the Wester Biggs ring.

Folklore

In Monteath’s (1885) account of local Dunblane traditions, the following narrative was given which local people held dear as a truthful statement of these ancient stones:

“Some antiquaries might suppose the ‘Seven Stanes’ to have been, in former times, a Druidical place of worship; but tradition contradicts this, in a manner so distinct and pointed, that none, in anyway acquainted with the connection which, in Scotland in particular, exists between oral testimony and written records, but must be struck with the plausibility of the story which tradition affords…

“The “Seven Stanes” then, instead of being the remains of a Druidical place of worship, tradition informs us, are intended to commemorate a glorious victory obtained by an army of Scottish patriots under Wallace over an English army 10,000 strong, who were taken by surprise and cut to pieces. Wallace, who was not less remarkable for the celerity of his movements than the strength of his arm, determined not only to intercept it, but formed, at the same time, the most daring plan of cutting off their retreat, as if already assured of victory. For this purpose he divided his brave followers into three divisions; one of which he dispatched in the night to the “Seven Stanes” – another was stationed at the Blackhill of Pendreigh, to fall upon the rear – and Wallace himself, with his division, lay on the Muir of Whiteheadston.”

References:

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones of Stirling District,” in The Stirling Antiquary, volume 1, 1893.

- Monteath, John, Dunblane Traditions, E. Johnstone: Stirling 1885.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian