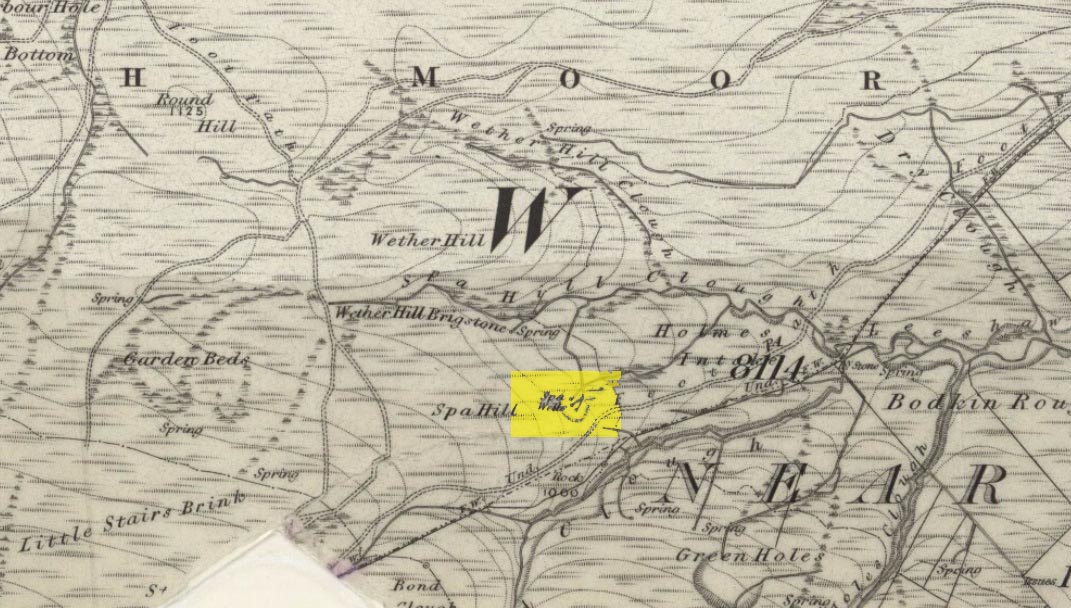

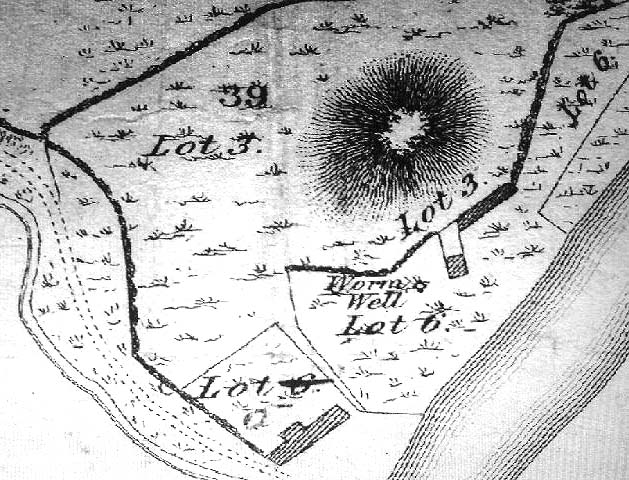

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SE 2633 8176

Also Known as:

- Mickel Well

- Mickey Well

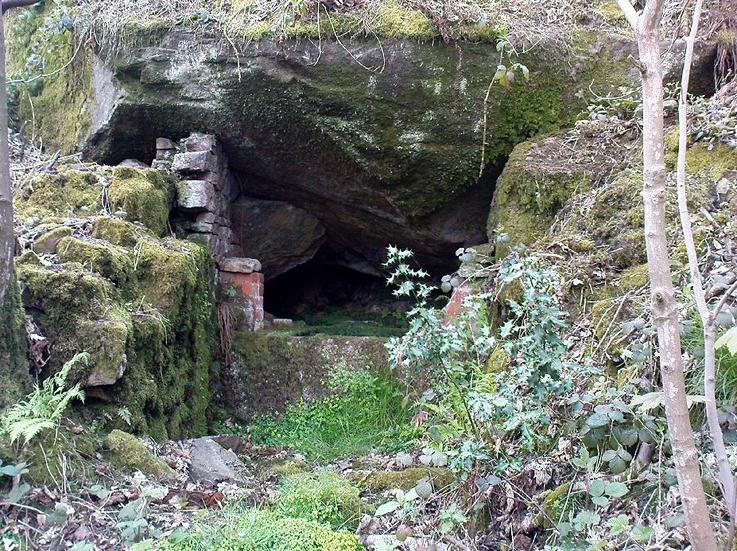

Found near the bottom of Holly Hill, as Graeme Chappell tells us, this old site “is located by the side of a narrow lane on the west side of the village of Well (aptly named). The OS map places the well on the north side of the lane, but this is only the outflow from a pipe that carries the water under the road. The spring actually rises at the foot of a small rock outcrop, on the opposite side of the road.”

Archaeology & History

Although the village of Well is mentioned in Domesday in 1086 and the origin of the place-name derives from “certain springs in the township now known as The Springs, St. Michael’s Well and Whitwell,” very little appears to have been written about this place. Edmund Bogg (c.1895) wrote that an old iron cup — still there in the 19th century — was attached next to this spring for weary travellers or locals to partake of the fine fresh water. Nearby there was once an old Roman bath-house and, at the local church, one writer thinks that the appearance of “a fish-bodied female figure…carved into one of the external window lintels” is representative of the goddess of these waters. Not so sure misself — but I’m willing to be shown otherwise.

Folklore

Around 1895, that old traveller Edmund Bogg once again wrote how the villagers at Well village called this site the Mickey or Mickel Well,* explaining: “the Saxons dwelling at this spot reverently dedicated this spring of water to St. Michael.” A dragon-slayer no less!

Although not realising the Michael/dragon connection, the same writer later goes on to write:

“There is a dim tradition still existing in this village of an enormous dragon having once had its lair in the vicinity of Well, and was a source of terror to the inhabitants, until a champion was found in an ancestor of the Latimers, who went boldly forth like a true knight of olden times, and after a long and terrible fight he slew the monster, hence a dragon on the coat of arms of this family. The scene of the conflict is still pointed out, and is midway between Tanfield and Well.”

This fable occurred very close to the gigantic Thornborough Henges! It would be sensible to look more closely at the mythic nature of this complex with this legend in mind. A few miles away in the village of Kirklington, the cult of St. Michael could also be found.

References:

- Bogg, Edmund, From Eden Vale to the Plains of York, James Miles: Leeds n.d. (c.1895)

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire, Cambridge University Press 1928.

* In old english the word ‘micel‘ (which usually accounts for this word) means big or great. On the same issue, the ‘Holly Hill’ in the case here at Well actually derives from the holly tree and NOT a ‘holy’ well. However, check the folklore of this tree in Britain and you find a whole host of heathen stuff.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian