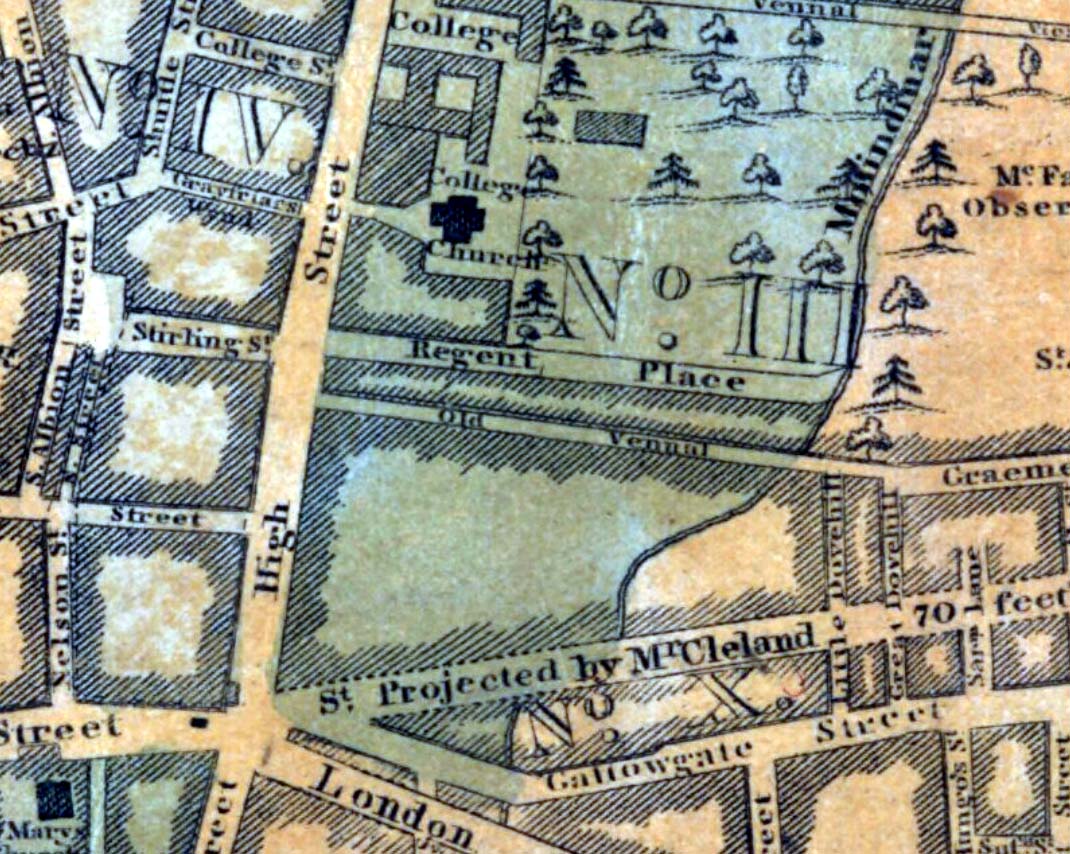

Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 598 649

Archaeology & History

One of the many public wells in Glasgow, all trace of this site disappeared long ago. Found at the ancient heart of the city, the name ‘Vennel’ comes from the old dialect meaning, “a narrow alley or lane between houses,” which is where it was once found, along the Old Vennel. An early account of it was outlined in MacGeorge’s (1880) classic text, where it was described as,

“a draw well, as there is a minute of council in 1656 arranging with John Scott, mill-wright, to ‘rewle and governe’ this well and ‘the new well in Trongait’, he undertaking to uphold them ‘in cogis and rungis, the toun vphalding all ganging greth quhan athir it weirs or breckis.’”

A few years after this in 1663, it seems the Vennel Well had been closed due to it becoming regularly polluted and further council minutes told:

“Recommendis to the deane of gild to caus open again the wall at the Stincking Vennell, and to remove the old wark therof, and caus mak it lyk the wall in Trongait for service of the inhabitantis.”

Around this time a door and lock was put around the well to prevent people dumping and polluting the waters. Further council minutes from April 1663 inform us that,

“The keyes of the well at the Vennell is delyvered to Robert Bell, tailyeour, and he is to have twa dollouris yeirlie for his attending thereupon.”

All healing virtues, folklore and traditions of this site have long since been forgotten.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Glasgow, TNA 2017.

- Brotchie, T.C.F., “Holy Wells in and Around Glasgow,” in Old Glasgow Club Transactions, volume 4, 1920.

- Grant, William (ed.), The Scottish National Dictionary – volume 9, part 4, SNDA: Edinburgh 1974.

- MacGeorge, Andrew, Old Glasgow, Blackie & Son: Glasgow 1880.

- Marwick, J.D. (ed.), Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Glasgow, AD 1663-1690, SBRS: Glasgow 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian