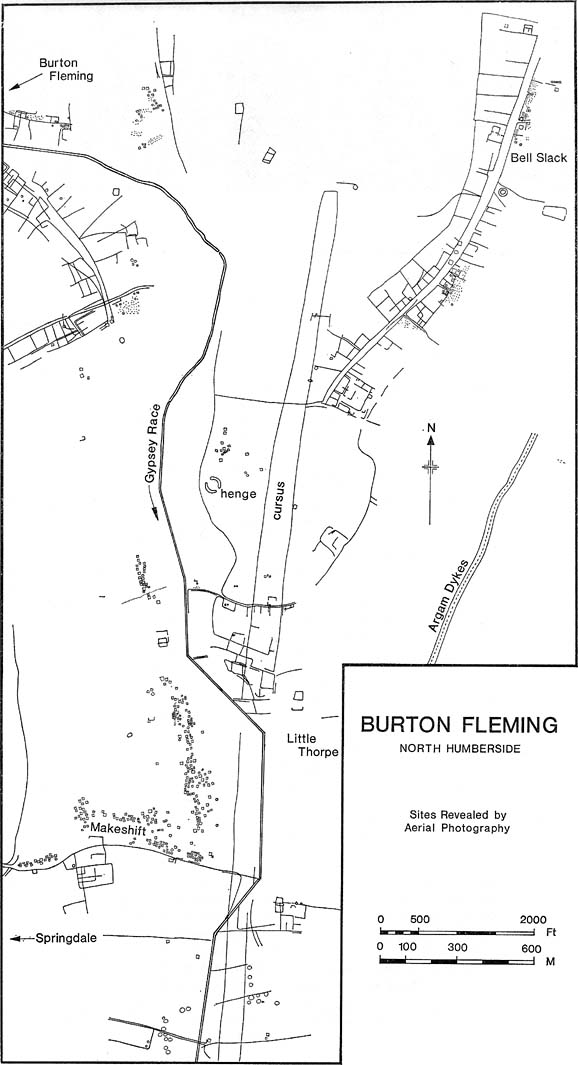

Cursus: OS Grid Reference – TA 099 717 to TA 096 679

Archaeology & History

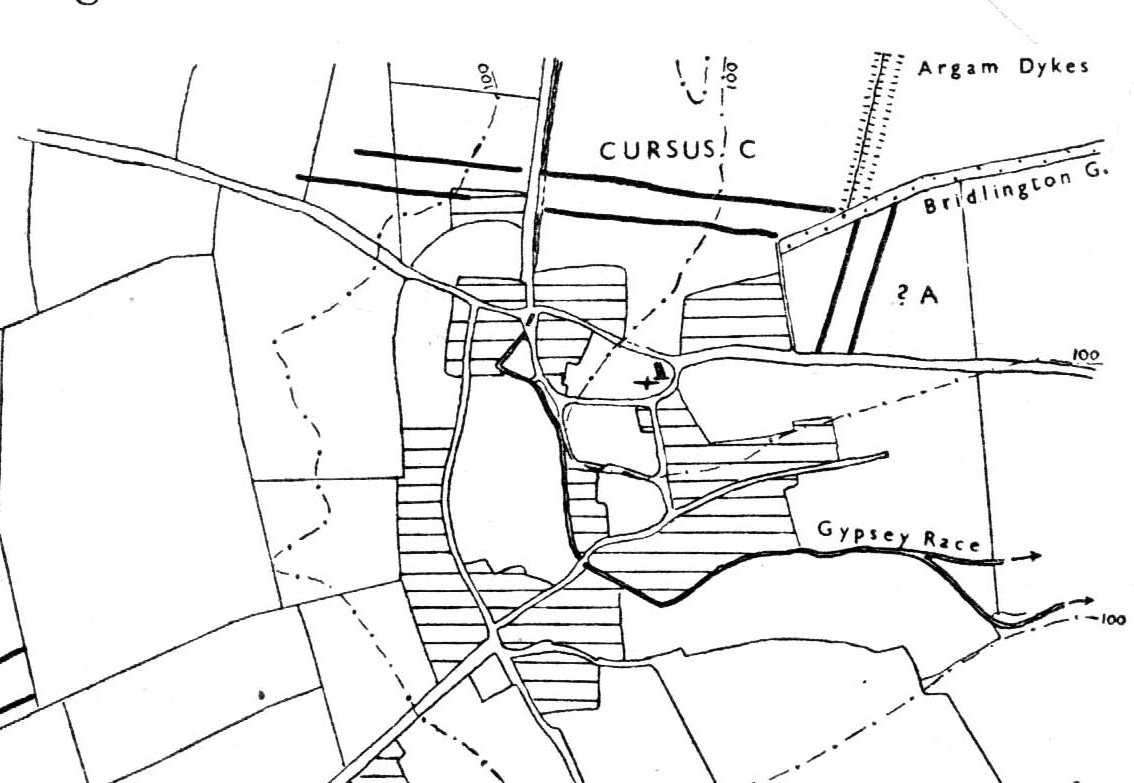

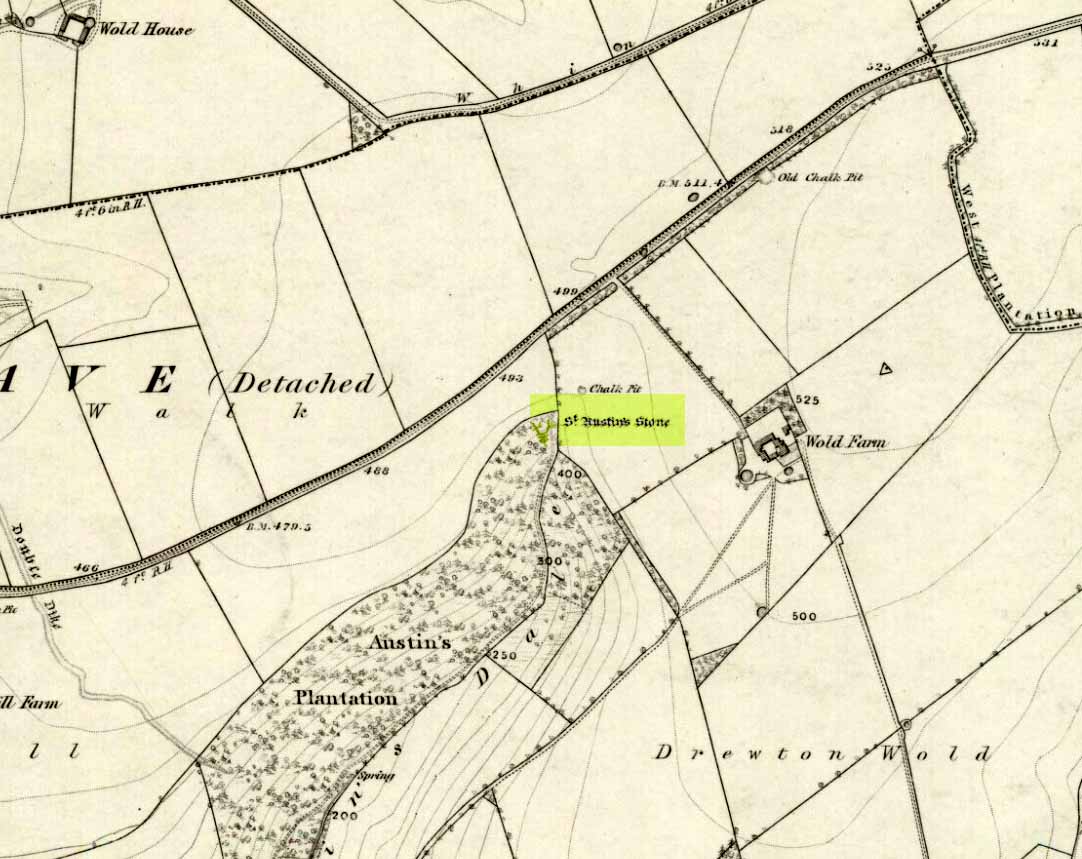

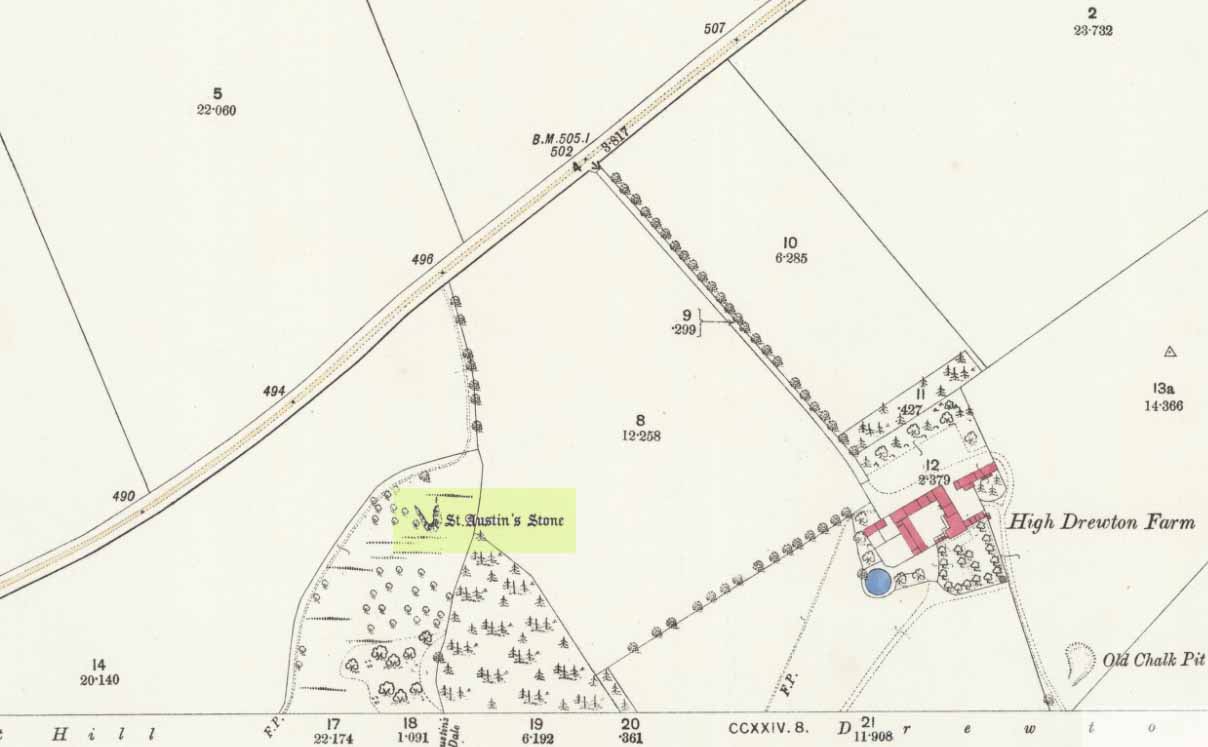

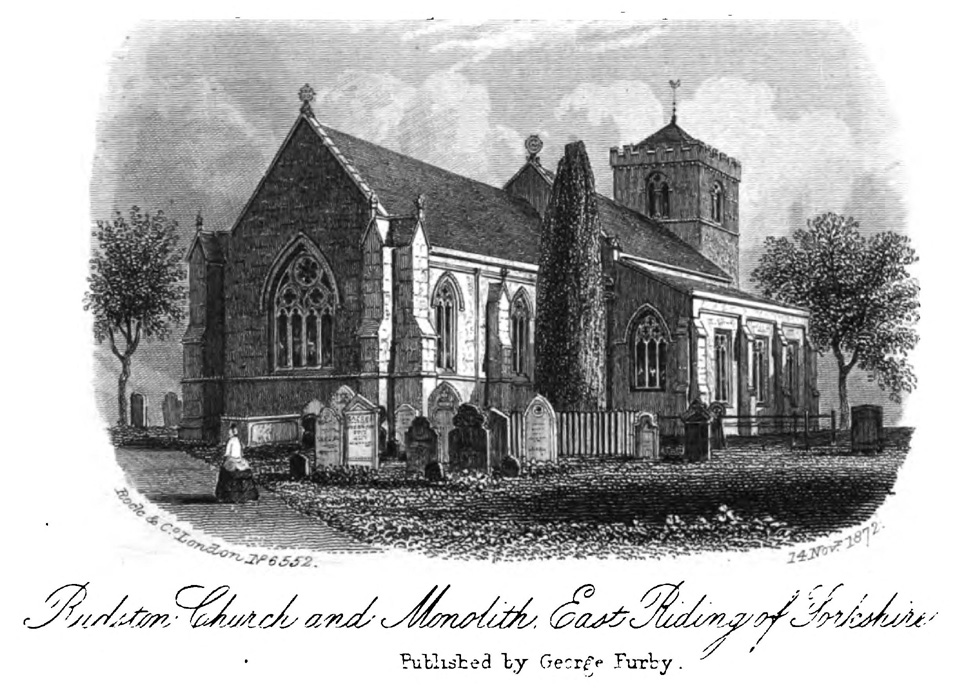

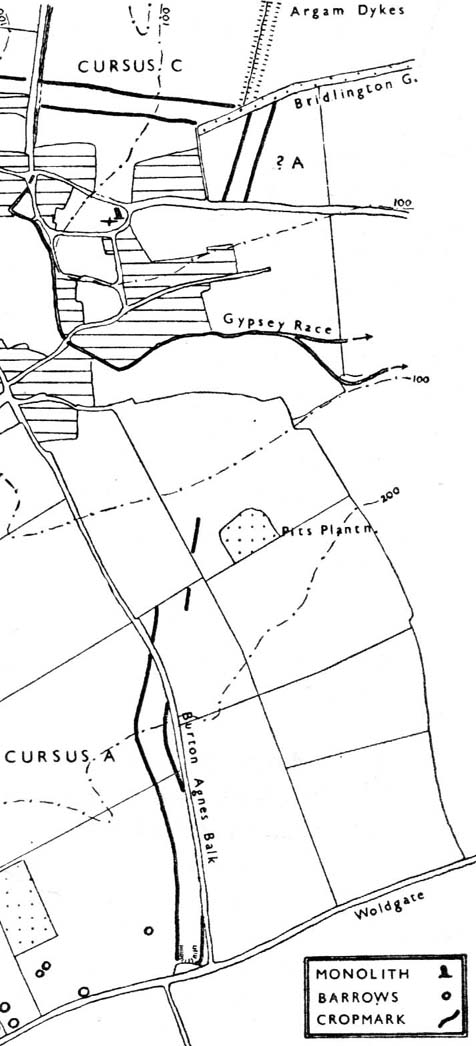

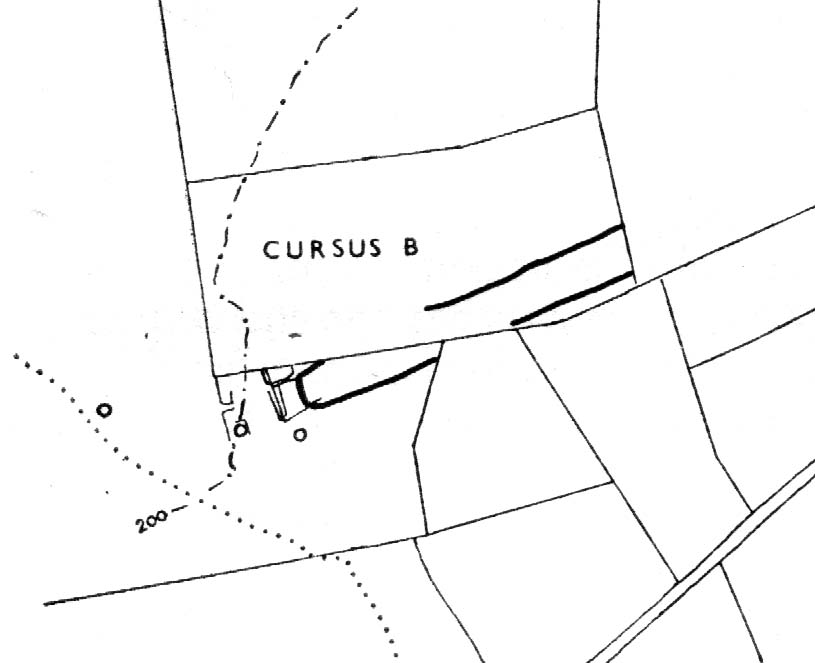

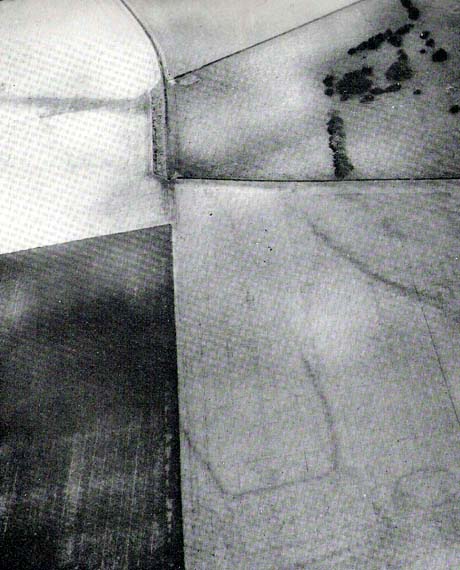

To the north of Rudston village and its giant standing stone, running roughly parallel with the divinatory waters of the Gypsey Race river and passing a mass of prehistoric remains en route, we find one the biggest prehistoric cursus monuments in the British Isles: the Rudston D cursus. More than twice as long as any of the three other cursus monuments nearby, its northern end or ‘terminal’ is flattened in nature (others are rounded) and is due east of the village of Burton Fleming starting at the intriguingly-named Maidens Grave field, just as the land begins to rise at TA 099 717. From here it begins its almost southern trajectory and runs almost dead straight for several hundred yards until edging, ever so slightly in direction, to a slightly more secure southern alignment. Past the site of the Rudston henge, the cursus broadens out slightly and, as it reaches the farmlands of Littlethorpe, edges slightly further to a more decisive direct southern route. The cursus then maintains a dead straight course for another mile, heading straight for, and stopping just short of the Rudston monolith in its modern churchyard. A short distance before we reach its southern end, archaeologists found that a section of the Cursus C monument cut right across it. Altogether, the Rudston D Cursus is more than 4km (2.3 miles) long! At its narrowest width, this monument is a mere 160 feet (50m) across, and at its widest is 280 feet (90m). A giant by anyone’s standard!

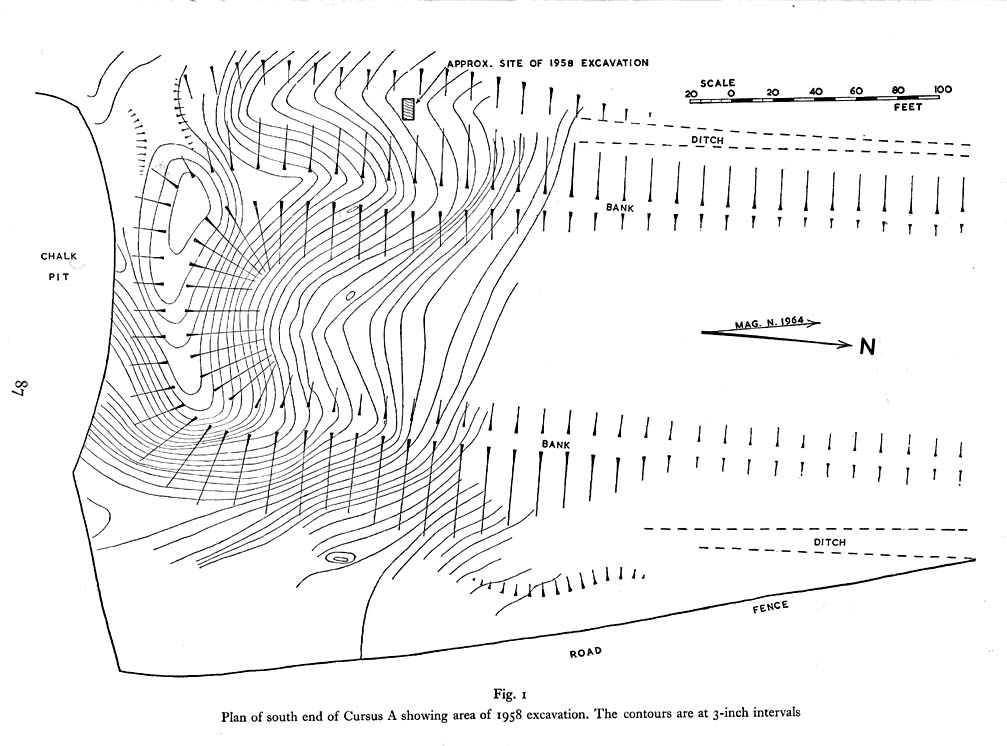

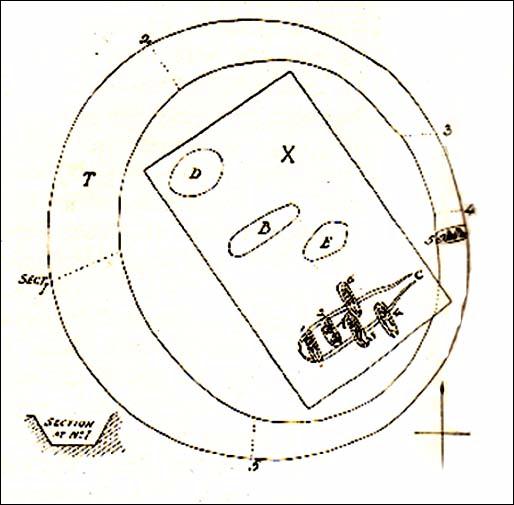

Along the entire length of this continuous ditch and inner bank there were just 3 small cuttings on the western side and three on the east, but two of the eastern openings were quite large. Some of these openings were affected by natural elements and others by modern agriculture. Today, much of this gigantic ritual monument (as the archaeologists call them) is not visible at ground level.

In visiting this area, make yourself aware of the other monuments in this class: the Rudston A cursus and Rudston B cursus, southeast and southwest of here respectively. A full multidisciplinary analysis of the antiquities in this region is long overdue. To our ancestors, the mythic terrain and emergent monuments hereby related to each other symbiotically, as both primary aspects (natural) and epiphenomena (man-made) of terra mater: a phenomenon long known to comparative religious students and anthropologists exploring the animistic natural relationship of landscape, tribal groups and monuments.

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, Rites of the Gods, J.M. Dent: London 1981.

- Harding, Jan, ‘Pathways to New Realms: Cursus Monuments and Symbolic Territories,’ in Barclay & Harding, Pathways and Ceremonies: The Cursus Monuments of Britain and Ireland, Oxbow: Oxford 1999.

- Loveday, Roy, Inscribed Across the Landscape: The Cursus Enigma, Tempus: Stroud 2006.

- Pennick, Nigel & Devereux, Paul, Lines on the Landscape, Hale: London 1989.

- Stead, I.M., ‘La Tene Burials between Burton Fleming and Rudston,’ in Antiquaries Journal, volume LVI Part II, 1976.

Links:

- ADS: Archaeology of Rudston D – Brief archaeological notes on the longest of the four known cursuses in the region.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian